Infection control in office buildings: Preparing for re-occupancy amid the coronavirus

Prior to the coronavirus outbreak, the AE firm Gresham Smith had a client in Tennessee that was in the process of consolidating 1,000 of its employees into an office building that already had 1,000 of its workers. This client “would never have discussed the words ‘free addresses’ or ‘shared desking,’” says Jack Weber, IIDA, LEED AP, the firm’s Senior Vice President and Design Principal. But after the virus spread to its market, “we’re doing planning to evaluate unassigned desking” for that company, says Weber.

“The consideration of additional remote working alternatives and possibly unassigned seating is to create greater desired flexibility for employees, now that the client has tested and invested in remote working and is gaining trust in its employees,” explains Weber. The other considerations are for future risk mitigation “that will increase business continuity and resiliency during future events.” Weber says a second client is also considering this future strategy.

The workplace, post COVID-19, is being viewed as “the first line of defense in preventing the spread of infectious germs,” states J. Kevin Heinly, AIA, LEED AP, Principal and Managing Director of Gensler’s San Diego office. In a paper he wrote about redesigning office lobbies, Heinly homed in on improving air quality, designing with antimicrobial materials, leveraging automation and voice activation, and using sensors to screen visitors.

It seemed that everyone had an opinion about workplace infection control. Even National Geographic chimed in with an article that explored how the pandemic exacerbated workers’ fears about returning to workplaces with open-office spaces.

MassMotion, Arup’s pedestrian dynamics and evacuation simulation software, can also be used to guide the design in environments like office buildings and parks with an eye toward social distancing. In the simulations, agents within six feet turn red and have their time in proximity logged to help test population and operational scenarios.

The digital library site Scribd posted a “Back to Work Checklist,” based on guidelines established by Congress’s bipartisan Member Problem-Solving Caucus, which laid out the public health and economic criteria necessary for workplaces to reopen, including “rapid and ubiquitous testing” and establishing a contact tracing database.

COVID-19 created a need for “workplace continuity” in such areas as crisis management, business planning, and disaster recovery planning, says Peter Miscovich, JLL’s Managing Director of Strategy and Innovation. Developers, building managers, AEC firms, and tenant companies had to think harder about what it would take to make returning office workers more comfortable and confident that their workplaces are continuously safe.

Post coronavirus: The future of office space is less densification

BuroHappold Engineering’s head of analytics Shrikant Sharma can’t see how workplace models that include assembly lines and open-plan offices would be tenable for the foreseeable future. Such settings “are not conducive to social distancing,” says Sharma, who is the Group Director of the firm's Smart Space team.

Using predictive modeling that draws on Internet-of-Things data sets, BuroHappold concluded that beyond 40% occupancy, “revisions to desk layout and high footfall areas will be needed” to keep occupants six feet from each other.

“The future of office space is less densification: far less benching and hoteling, more private areas, more virtual meetings,” concurs Andrew Horning, LEED AP, Vice President and COVID-19 Task Force Leader with Bala Consulting Engineers. During the pandemic, Bala published a white paper that offers detailed infection-control guidelines and solutions for HVAC, filtration, bipolar ionization, UV lighting, pressurization and airflow, humification, ductwork sanitization, and air purification, as well as separate solutions for plumbing, technology, and workplace environment.

Bala recommended imposing greater control on what and who come into buildings. It anticipated greater demand for negative air pressure in common areas like kitchens, says Scott Davis, PE, the firm’s Vice President and COVID-19 Research Leader. The coronavirus’ aftermath could even trigger more building renovations and repurposing, says Charles Kensky, Bala’s Executive Vice President and COVID-19 Research leader.

“It’s safe to say that we won’t go back to the way things were,” says Steve Riojas, Global Director of Education and Technology with HDR. Sharron van der Meulen, Partner and Interior Design Practice Leader with ZGF Architects in Portland, Ore., added that as people returned to their workplaces, tenants “will need to do some backtracking on space and amenities” to discourage workers from gathering in larger groups.

To that end, Cushman & Wakefield, Hines, Delos, and the Well Living Lab in late April announced a collaboration to evaluate methods and establish guidelines for a safe return back to work. The Lab, which is adjacent to the Mayo Clinic campus in Rochester, Minn., is using its office space to gauge practices and technology that might reduce the risk of respiratory virus transmissions.

Cushman & Wakefield is contributing workplace strategy and design protocols. Delos is lending its expertise in air filtration. And Hines, with a global real estate portfolio of more than 500 properties, is drawing on its six decades as a leading developer.

Prior to this announcement, Cushman & Wakefield’s Recovery Readiness Task Force released a “tool kit” and protocols for tenants to transition back to work. This includes a “6 feet office” concept whose traffic routing is laid out to ensure employees are maintaining social distancing. The elements of this concept include an analysis of current working spaces, workable agreements and rules with employees for personal safety, workstations with personal protective components, training for facility managers, and a certificate stating that these measures are being implemented.

Cushman & Wakefield’s “6 feet office” concept

Along these same lines, Daniel Yudchitz, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP, Senior Design Architect with Leo A Daly in Minneapolis, recently sketched out a space utilization concept that reimagines the office as a mix of remote and centralized work. Dubbed “Converge and Disperse,” the concept foresees the amount of space that a tenant can “own” shifting dramatically, with shared or “elastic” amenities becoming a bigger part of a building’s offering.

Space shared by multiple tenants on each floor could lead to experimentation with new materials and assembly patterns to enable flexibility. And when workers must disperse, buildings could save energy by being divided into zones whose energy and electricity could be shut down.

Will social distancing stick in the commercial office market?

None of the AEC sources interviewed by BD+C imagined that human interaction in workplaces would come to a halt. Sustaining social distancing, though, will also require discipline that tests the limits of most workers’ adaptability.

“Clients that place a premium on culture will likely always want a robust physical workplace,” says Lise Newman, AIA, Vice President and Workplace Practice Director with SmithGroup.

But even she thought open benching was a thing of the past, and that workers henceforth will expect companies to supply them with personal hygiene aids, like wipes to disinfect keyboards, desktops, and unassigned seats.

“Changes in workspaces will likely be more behavioral than physical,” observes Fred Schmidt, FIIDA, LEED AP, a Principal in Perkins and Will’s Chicago office. Associate Principal Michelle Osburn adds that companies need to alter their policies to make it more culturally acceptable for employees to stay home when they’re not feeling well. “The argument that you ‘need’ to be in the office to do your work has been proven false on a stunning scale,” she says.

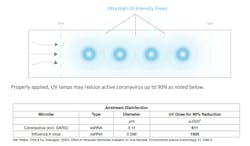

In its white paper on COVID-19 and the impacts to the workplace, Bala Consulting Engineers provides several HVAC solutions to infection control, including UVC lamps installed within an MEP duct system to kill microorganisms in the airstream.

Remote working might have been more prevalent, before the virus hit, than most people knew. Rebecca Milne, LEED GA, Perkins Eastman’s Director of Design Strategy, recalls reading a 2016 study that estimated 43% of U.S. employees worked remotely at least occasionally, and that on any given day 50% to 60% of office desks were empty.

Angie Lee, Vice President and Global Sector Leader-Office Workplace for Stantec in Chicago, cites another recent survey that found nearly three-quarters of the companies polled saying they would move at least 5% of their positions to remote working.

WRNS Studio in San Francisco, which has four offices and 200-plus employees, “took our business to the cloud years ago, so remote working during the pandemic wasn’t such a big deal,” says Sam Nunes, the firm’s Founding Partner. While he doesn’t think WRNS would ever go 100% remote, he can envision more online collaboration as employees rotate in and out of his company’s offices. “A lot of this will be HR-driven,” and depend on new protocols for human interaction, he predicted.

James Woolum, AIA, IIDA, a Partner and Interior Architect at ZGF Architects in Los Angeles, speculated that somewhere between 30% and 40% of companies’ future workforces could be working from home regularly. And if there are 60 employees in an office that once accommodated 100, “spreading them out for social distancing will be easier.”

Whatever number of workers eventually works from home, “the entire digital platform will become a very big deal” to facilitate virtual collaboration, says Stantec’s Lee. She also thought that Stantec would need to provide its workplace clients with designs that include larger assembly spaces for when companies bring together their associates at different times of the year. Those designs, she says, would require code changes pertaining to exits and life safety, as well as the number of restrooms needed for that space.

Touchless and wellness are dual objectives in office design

Greater attention to hygiene and cleanliness will distinguish the workplace of the future. “The short-term impact of the virus will be more personal space. Handwashing will become more of a regimen,” says Connor Glass, Principal and Design Director with Perkins Eastman.

While some AEC sources, like Gresham Smith’s Weber, say their clients aren’t quite ready to discuss antimicrobial solutions, the general consensus among AEC sources is that healthier materials will be deemed essential for workplaces. “Wellness will be ascendant,” says WRNS’s Nunes.

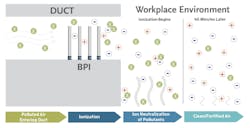

Bipolar ionization, an infection control solution proposed by Bala Consulting Engineers, releases positive and negative ions into the airstream to help the building’s filtration system capture contaminants.

Technology will come into play in such areas as advanced cleaning and sanitizing practices, touchless interaction with objects via automation or voice activation, and the use of UV lights, biometrics, and temperature-monitoring devices that prevent germs from wafting into the building.

“Air quality is one of the most compromised aspects” of a building, says Shona O’Dea, BEMP, RESET AP, WELL AP, LEED AP, Senior Associate and Building Performance Analyst with DLR Group. That’s particularly true of office buildings, where only 25% of their airflow comes from the outside. But indoor air quality has mostly focused on improving employees’ cognition and productivity, notes Milne of Perkins Eastman.

The presence of the coronavirus has shifted that conversation to infection control. In a paper on achieving healthier working environments, Stantec’s Sustainability Team Leader Rachel Bannon-Godfrey grouped indoor air quality with building conditions assessments, handwashing infrastructure, industrial hygiene, and mental health design support. Her recommendations include adapting building controls and sequencing to accommodate and monitor additional filtration needs.

ALSO SEE: How the coronavirus is impacting the AEC industry

In a subsequent interview with BD+C, Bannon-Godfrey added that clients in general are showing more interest in the WELL Building Standard, which includes ventilation and airflow guidelines, “to determine what constitutes a healthier office.”

More firms are positioning themselves as wellness champions these days. Casey Lindberg, PhD, Associate AIA, Senior Design Researcher with HKS, spoke of the opportunity presented by the virus outbreak to connect buildings more directly with nature and air quality. Stantec, notes Bannon-Godfrey, sits on the International Well Building Institute’s COVID-19 task force, which has been analyzing the pandemic to see where its guidelines might need tweaking.

The workplace, though, won’t change overnight. Several AEC sources cautioned that making workplaces healthier will require code amendments, fundamental behavioral changes on the parts of employees and property managers, and clients who can see the long-term benefits of wellness that might include costly MEP and HVAC upgrades in existing buildings.

That’s a lot to expect from Americans who, in cities around the country, ignored social distancing and stay-at-home mandates. But workplace etiquette won’t tolerate such a cavalier attitude toward infection control, predicts ZGF Architects’ Woolum, who sees the future workplace as “a convergence of nature, design, and martial law.”