Wood’s strength depends on the direction of the grain. The technical term for this variance is “orthotropic,” which means having different strengths in three planes perpendicular to each other. Wood grain is strong in the longitudinal direction. Think of narrow wood columns used to support much larger beams and roof trusses as a classic example of this longitudinal strength. However, wood is not as strong when loaded perpendicular to the grain. The direction opposite to a tree trunk’s vertical growth is wood’s weakest. Too much tension perpendicular to the grain pulls wood fibers apart and can lead to catastrophic failure. Notching, misplaced fasteners and hanging loads can all contribute to this kind of failure. On the other hand, structural designs that take advantage of wood’s longitudinal strength and avoid cross-grain tension stresses are efficient, attractive and more resilient.

Proper connection details are critical to the structural performance and serviceability of any timber-framed structure. While this is true for solid sawn as well as glued laminated (glulam) timbers, the larger sizes and longer spans made possible with glulam components make the proper detailing of connections even more critical. Careful consideration of moisture-related expansion and contraction characteristics of wood is vital in detailing connections to prevent inducing tension perpendicular-to-grain stresses. Connections must be designed to transfer design loads to and from a structural member without causing localized stress concentrations, which may initiate failure at the connection.

7 Best Practices for Glulam Connections

- Transfer loads in compression bearing whenever possible.

- Allow for dimensional changes in glulam due to in-service moisture cycling.

- Avoid details that induce tension perpendicular-to-grain stresses in a member.

- Avoid moisture entrapment at connections.

- Do not place untreated glulam in direct contact with masonry or concrete.

- Avoid eccentricity in joint details.

- Minimize exposure of end grain.

Designing and Detailing Connections for Shrinkage

To last, exterior connections must be properly vented and drained. Avoid leaving wood in direct contact with concrete, masonry or grout, which are porous and wick moisture. It’s also critical to detail connections to isolate all wood members from potential sources of excessive moisture and vent to allow wood to dry. Since wood expands in moist or humid environments and shrinks in dry environments, it is important to design connections that allow for these movements. Connections that are not detailed correctly for wood shrinkage can cause splitting. Detailing connections with slotted holes allow wood movement without causing stresses perpendicular to the grain that may cause wood to split. Shrinkage of the wood can also result in loose connections that can alter the intended load path, while swelling can deform connection hardware. Good wood connection details allow for these natural tendencies.

While expansion in the direction parallel to grain in a wood member is minimal, dimensional change in the direction perpendicular to grain can be significant and must be considered in connection design and detailing. A 24-inch-deep beam can decrease in depth through shrinkage by approximately 1/8 inch as it changes from 12%-8% in equilibrium moisture content. In designing connections for glulam members, it is important to design and detail the connection such that the member’s shrinkage is not restrained. If restrained, shrinkage of the beam can cause tension perpendicular-to grain stresses to develop in the member at the connection. If these stresses exceed the capacity of the member, they may cause the glulam to split parallel to the grain. Once a tension-splitting failure has occurred in a member, its shear and bending capacity are greatly reduced.

In addition to the moisture-induced tension perpendicular-to-grain failures discussed above, similar failures can result from a number of different, incorrect connection design details. Improper beam notching, eccentric (out of plane) loading of truss connections and loading beams from the tension side can induce internal moments and tension perpendicular-to-grain stresses.

Effects of Moisture Accumulation

As most connections occur at the ends of beams where the wood end grain is exposed, it is critical that these connections be detailed to prevent moisture accumulation. This can usually be accomplished by detailing connections that allow moisture to drain. These details include holes or slots in box-type connectors or open-ended connection, and by maintaining a gap of at least 1/2 inch between the wood and concrete or masonry construction. Because most connections require the exposure of end grain due to fastener penetration, even those connections that occur away from beam ends must be considered potential decay locations. Field studies have shown that any metal connectors or parts of connectors that are placed in the “cold zone” of the building (that area outside of the building’s insulation envelope) can become condensation points for ambient moisture. This moisture has ready access to the inside of the beam through fasteners and exposed end grain.

Spread Out the Load

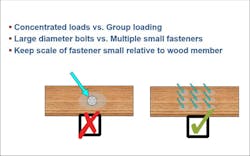

It is often said that many hands make for light work. The same can be said for connections. It is better to use multiple small fasteners rather than one large fastener. Concentrating loads through a single connection can overstress wood’s capacity. Rather than creating a concentrated load by using one large-diameter bolt, it may be better to spread out the load by using many small fasteners instead to provide redundancy and a reduced load at each fastener.

Find illustrated guidance and visual examples for designing timber-frame connections and avoiding common connection errors in APA’s free Glulam Connection Details design and construction guide.