A leading AE firm probes the power and promise of technology-assisted design

Talk of a revolution has been incessant for the past few years: from revolutionizing how people learn to work and, most radically, how they create, talk of the power of generative artificial intelligence (AI) has been promising if not grandiose.

It’s not an unfounded conversation. From smartphones with predictive texting to smart home thermostats that learn occupancy patterns, AI has infiltrated everyday activities that are both seen and unseen.

This new phase of AI, though, is sparking more than discussions. It’s sparking ideas of a rapid transformation in how businesses operate, and for good reason. A 2023 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that AI-enabled tools improved productivity by an average of 14%, with that increase at 34% for novice and low-skill work. Additionally, researchers found that AI assistance can improve worker retention and promote worker learning.

The findings aligned to those from a different study that showed a 1% increase in AI penetration can produce a 14% increase in total productivity.

Yet, from what the peer-reviewed studies show, history is also littered with the unfulfilled promises of technological advances. For engineering firms, realizing the potential of generative AI and large language models requires an approach that is measured, intentional and assistive for staff, rather than prescriptive.

Fitting AI to need

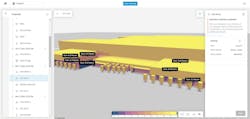

AI is transforming architectural workflows by streamlining early-stage design and reducing inefficiencies. Tools like Forma provide immediate environmental feedback, enabling architects to refine options quickly without extensive modeling. This integration of environmental analysis into the decision-making process ensures sustainability goals, such as embedded carbon analysis and energy efficiency, are addressed. By minimizing redundant modeling efforts, AI allows architects to focus on innovation and design excellence.

In pursuing technology-enabled operational efficiency, framing the purpose of the technology often shapes how well it is received by those who will use it. For the implementation of AI, this means seeing it as more than an automation tool. It means defining its capabilities as an enabler tool, and, more importantly, engaging the staff in developing that definition.

Initiating an AI solution for staff, we began by polling employees on which tasks they find most mundane that AI-enable technology could automate. With more than 100 responses, about a dozen trends were identified. Leveraging outside expertise, we then examined the quality of our data to organize the trends around possible solutions.

With those results, leaders were able to determine which problems would benefit most from an AI solution.

While the promise of AI has always been promoted in what it can produce, its real power is what it can do to complement employees in their work by eliminating time-consuming and repetitive tasks that free staff to focus on more high-value and professionally stimulating solutions in the production process.

Seeing this possibility, though, also meant seeing AI tools as more than a Super Google. Embarking on our journey, our team started with education and ideation that led to a machine learning project for staff forecasting and assignment optimization. From this work a large language model (LLM) was rolled out – in our case, Microsoft Copilot that ensured the security and confidentiality of our data. It is critical to note that in advance of making Copilot available, our team published a data ethics standard, an AI Governance Charter, an update to the Employee handbook that addressed AI applications and their responsible use, as well as developed an AI training module. We did not mandate that staff take the training to identify enthusiasts. At the same time, we set the policy to not activate a Copilot license for staff unless they complete the training.

For AI, the biggest adoption obstacle is demystifying the technology; the next is understanding its capabilities. Beyond search, what our team quickly learned is the ability of AI to analyze data more quickly than humans.

Take a typical RFP. What sometimes took up to a day to analyze scope, schedule, contracting method and a project execution vision could quickly be summarized by AI to enable the team to make a well-informed and rapid decision about whether to pursue a project. In turn, with a more expedient decision-making approach, the team could focus on developing a winning strategy and preparing the proposal.

Training, and being trained

AI training programs in architecture must incorporate real-world case studies and structured support for prompting techniques to ensure all staff, regardless of experience level, can maximize AI’s effectiveness. While younger designers readily adopt AI as part of modern digital workflows, seasoned architects may benefit from hands-on demonstrations to see its value in enhancing rather than replacing the design process. Comprehensive training and practical applications can bridge this gap, ensuring AI adoption benefits all practitioners.

In adopting our LLM, our team took training to learn how to interact with, or prompt, the model to reap the most benefits. The team learned how to give the model detailed information for it to be effective.

The key to unlocking its capabilities is understanding its genesis. Humans programmed the model, so it will give human-like responses. Using this technology can sometimes feel like interacting with an unpredictable teenager, as a result, expectations should be set accordingly.

For example, a document summary could be different each time because AI is not designed to be repeatable. It’s designed to “think” like a human. Like two engineers summarizing a document differently, AI can produce varying summaries.

This makes AI suspect with audiences like engineers. Engineers often expect computer systems to be completely predictable, repeatable and reliable, because that’s how programming has been up until the advent of AI systems. It can make adoption challenging.

Knowing how to interact with the LLM can improve the quality of the information produced. By giving the program detailed information rather than a few unconnected sentences, not only does the quality of the output increase, but it allows the model to learn and improve the consistency of the responses.

By implementing AI as a process improvement tool rather than a solution to redefine the business, its adoption has been easier. Moreover, AI’s implementation is not a destination, it’s an ongoing process with project teams in continual back-and-forth testing.

Promising technology-assisted design

Owner concerns about speed-to-market are valid, and AI solutions must directly address these challenges. AI has the potential to accelerate project delivery while maintaining accuracy by streamlining early-stage design decisions and integrating cloud-based platforms.

Tools like VERAS and Forma enable rapid refinement during the conceptual design phase, reducing processes that once took hours to mere minutes accelerating our design leads ability to evaluate multiple creative solutions to guide the owner and project to the best outcomes. This could be energy and form, or a layout decision for a more sustainable and efficient building, or doing several material interactions in renders to capture the intent of the design.

Well into the construction document and administration phase of a project, AI can also improve the submittal review process. We have seen Ai-Assistants help in comparing products, creating submittal logs and quickly review if the submittal conforms with the specification. This minimizes the back-and-forth verification and cuts response times. This acceleration enhances collaboration between architects, engineers, and clients while ensuring projects meet sustainability, design intent, and performance goals.

As these programs become more complex, they will be able to respond more naturally to engineering language and become more familiar with how to interpret design images, leading to higher-quality work. Time-consuming RFIs could be answered more efficiently and effectively, enabling engineers to focus on more complex solutions and reducing costs to clients.

Similarly, AI could impact project delivery by reducing time and cost while increasing quality. Like AI predicting the next word in an email, eventually, it will be able to predict applicable details using the context of the system or the type of space being designed, like a boiler room with AI understanding the type of systems and codes that are applicable in the context.

Finally, as we’re discovering, AI can improve a firm’s abilities to solve complex problems more effectively—not by executing the problems, but by assuming the mundane tasks that allow engineers to focus on the problems. Engineers excel at using their problem-solving skills to solve unique challenges. By alleviating engineers of the responsibility for tasks that don’t require such skillsets, AI improves the actual work environment by elevating staff to do what inspires them, possibly shortening the time to market and making that quality of the solutions shine.

Better quality, better delivery, and better problem-solving—the possibilities that come with AI are intriguing. While not fully realized yet, AI is far from an empty promise. By adopting AI-enabled technologies with a realistic expectation to enhance efficiency rather than merely automate tasks, firms can refocus on what makes human-driven design effective. Engineers and architects alike can leverage AI to explore complex solutions buried within routine work, unlocking new levels of innovation.

AI represents an evolution rather than a revolution through this lens, elevating design and engineering for those drawn to its challenges. Integrating AI-driven natural language models into workflows enhances decision-making, communication, and design coordination in architecture. Cloud-centric systems improve collaboration and real-time responsiveness, addressing key project bottlenecks. By embedding AI agents and AI triggered processes into cloud-based platforms, architects can prioritize creativity and design integrity while AI handles data-heavy or redundant tasks, reducing inefficiencies and improving project outcomes.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Brett Susany is Senior Vice President for AI Integration at SSOE Group, and a member of its Executive Management team