Some of the most cutting-edge things going on behind-the-scenes in architecture today involve advanced 3D modeling and digital design technology. Architects and designers are now using game-engine technology for better/faster visualization and design.

And then there’s 3D printing technology. Several teams around the globe are working to bring 3D printed houses to market. It’s incredible, but houses can now be made (potentially, in one day) by a huge, computer-controlled, 3D printer that extrudes a concrete mix in successive layers through a giant nozzle.

So what seems odd is that, by and large, we as a global society don’t design our cities with any sort of three-dimensional wizardry, much less 3D thinking. We know most cities have tall buildings, but we don’t think that a city—the attributes of urbanism—could potentially be reoriented vertically and placed inside tall buildings. Nor do we think that the city is really a three-dimensional object with all sorts of untapped planes. By and large, we connect as a populace on just one of them—street level. Anything above or below ground, other than public transportation, is generally not mined as public space.

"For cities to be great, we certainly have to take care of basic services, housing, and infrastructure. But we also have to think about how we’re going to inspire people and bring them together in interesting ways and make the city feel good." — Andy Cohen

But when you consider world urbanization data, which includes the rise of mega-cities with populations of more than 10 million people, and the fact that most mature cities don’t have extra space at ground level, we’re going to have to start mining the other levels of our cities. We need to consider the vertical elements of urbanism—vertical urbanism—and find new ways to connect people to city life in places other than the ground plane.

Futuristic? Gardens and parks in the sky? Buildings that connect to each other via walkways that are located on, say, the third floor? Underground bike paths?

There’s nothing sci-fi or scary about livability and connecting people, and that’s what we’re talking about here. Livability is often overlooked as a vital attribute of a city and is often relegated to bonus land.

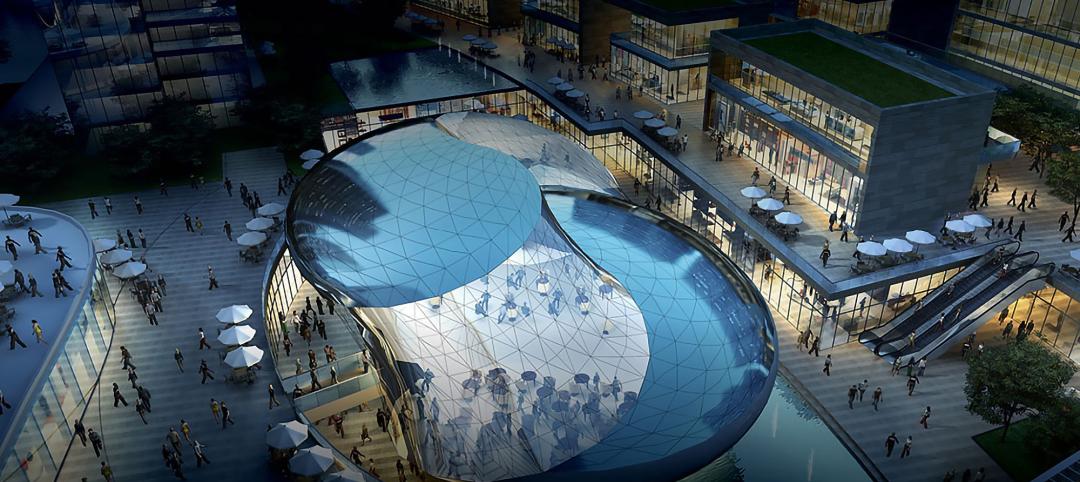

The Shanghai Tower, Jin Mao Tower, and Shanghai World Financial Center.

The Shanghai Tower, Jin Mao Tower, and Shanghai World Financial Center.

We have that wrong. For cities to be great, we certainly have to take care of basic services, housing, and infrastructure. But we also have to think about how we’re going to inspire people and bring them together in interesting ways and make the city feel good. That’s how innovation happens. And that’s how our cities become “hubs” and “centers” and resilient.

We know open space is critical to connecting people and this whole idea of livability. But how do we find it in super high-density places like Beijing, Mumbai, and Lagos (Nigeria) and in world capitals like London and New York?

The answer is we have to create it. That’s where vertical urbanism and 3-D thinking come into play. We have to envision the city as a three-dimensional object and leverage space that’s already there, yet remains untapped.

Hong Kong does this particularly well. It’s a compact, hyper-dense, intensely vertical city with challenging geography—steep hills, water, little flat ground—but it feels good to move around in that city. And that’s, in part, because the city uses its other dimensions. It connects on many levels other than the traditional ground plane.

Hong Kong cultivated its air space and created a whole network of public spaces via elevated walkways and streets, escalators, and bridges that connect buildings to buildings and hillsides. Three Australian architects use the term “volumetric” to describe the city’s 3-D urban planning strategy in their book “The Making of Hong Kong: From Vertical to Volumetric.” They make the case that Hong Kong, because off its complicated geography and compact footprint, is “an accidental pioneer of a new kind of urbanism.”

We need to learn from that “accident.” And, indeed, we are starting to see some progress with cities cultivating their verticality.

In London, Rafael Vinoly’s 20 Fenchurch Street, a.k.a. the Walkie Talkie building, has a public sky garden at its top, although the British are still debating how public it is, how much of a garden it is, and how much they like the building. Still, big picture, it’s a move forward for vertical urbanism. It’s this idea that a city’s tall buildings could harbor public space off the ground plane.

Taking the idea even further is Shanghai Tower. When it opens later this year, Shanghai Tower will be China’s tallest building and the world’s second tallest. It also will be the only megatall or supertall in the world whose perimeter—the most valuable real estate in tall buildings—is entirely devoted to public space.

The Shanghai Tower's curtain wall.

The Shanghai Tower's curtain wall.

Gensler conceived this mixed-use tower as a new prototype for a vertical building—one that reimagines urbanism and the intersections of people and experiences that make a city vibrant, as a vertical construct. We designed seven sky gardens, located every 12 to 14 floors as the tower rises to its 632 meter height. These open spaces are positioned between the building’s two skins and serve two key functions. First, they organize the giant building into smaller, more intimate “neighborhoods” and provide a gathering spot—a town square—for people who work in the building and, in particular, in that stretch of floors. And second, for the public-at-large they were meant to be parks in the sky, a place to meet for lunch, read a book, and explore the density of this mega-city from a completely different, vertical perspective.

A new underground walkway will link Shanghai Tower to the two nearby supertalls. That pathway will be an important connection, creating a community among these three skyscrapers and another, quieter “ground plane” in Shanghai’s busy Pudong district where mega-boulevards dominate the streetscape and frustrate pedestrians.

Indeed, cities ought to be looking downward, as well, for their verticality and for other “ground planes.” And a number famously have.

Montreal has an extensive Underground City. Tokyo has a reported 63,000 underground areas that include underground paths and shopping complexes. Seoul, South Korea, has one of Asia’s largest underground shopping malls, the COEX Mall, which was just renovated; the land value there has almost doubled since the upgrade was done.

The London Underline.

The London Underline.

London, too, is looking underground for new and interesting space that people will embrace. A conceptual project called The London Underline seeks to create a subterranean bike and pedestrian path. That path would wind through the city, reduce street-level congestion, keep walkers and riders out of the rain, and give people a new, underground experience of this increasingly crowded world capital.

Here’s the key to it: That subterranean “ground plane” already exists. The Gensler designers from our London office who came up with the concept, repurposed disused metro tunnels and surplus infrastructure (not just the tube tunnels but exchanges, stations, and reservoir chambers) and turned these spaces into the network of cycling and walking paths that forms the Underline. Pop-up businesses, exhibitions, and other retail could live down here too. And this whole “hidden London” would be powered by Pavegen, a kinetic energy system that converts footsteps into electricity.

Indeed, movement is essential to a city’s livability. While roads and highways and public transportation systems dominate the discussion of a city’s ability to move, it’s also important for cities to consider the roads “less traveled by,” the paths meant to inspire as well as transport. Perhaps that’s a subterranean bike path. Or an elevated pedestrian walkway. Or maybe it’s a reclaimed dry riverbed turned into a pedestrian highway, as is the case in Mecca.

Mecca is a city that deeply understands the importance of movement and inspiring people—and thinking three-dimensionally about its urban planning. Annually, it hosts the largest migration of people on the planet, which people of the Muslim faith know as the Hajj, a once-in-a-lifetime religious experience for Muslims. Some 5 million Muslims from all over the world are now projected to travel to Mecca every year to make their pilgrimage.

Makkah.

Makkah.

Those participating pilgrims move in waves along the predetermined Hajj route that traverses approximately 15 miles in and around “Makkah.” Certain segments of it must be completed within a specific time period, and the faithful are also required to perform the prescribed rituals along the way, and all in five days for a proper Hajj to be completed. This can create enormous crowd conditions that have been measured and simulated in durations as small as 15-minute increments to show points of congestion.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia took those movement problems seriously and brought Gensler onboard more than a decade ago to provide ongoing consulting support that would help the Kingdom better serve its guests. The solutions we devised together required 3-D thinking.

To address the first bottleneck that occurs at the start of the pilgrimage in the Plain of Arafat, when this sea of humanity starts walking through a constrained valley, we created another “ground plane.” We reclaimed a dry riverbed and turned it into a pathway running perpendicular to the primary route. This allows people moving toward their next destination to naturally redistribute themselves, still, though, moving in the prescribed direction, still respectful of the ritual.

Another bottleneck occurs near the end of the Hajj when the pilgrims must walk seven times around the Ka'abah in the Holy Mosque. Our movement studies showed that with a single ground level, only 1.2 million pilgrims could possibly complete that ritual in the single day time required. Clearly, the need to increase this capacity was vital for the future projected numbers of pilgrims. The solution was a series of architecturally sensitive platforms that are respectful of the Holy Mosque and continue to give pilgrims eye contact with the Ka’abah. The platforms allow multiple levels of people to participate in the Tawaf, the walk around, within the prescribed time, so a significantly increased number of pilgrims can complete their spiritual journey in accordance with their beliefs.

Today’s great cities must be resilient—and open—to many things, including the influx of humanity. As the world gets more urban (by 2050, 66% of the world’s population is expected to live in urban areas, up from 54% today, according to data from the United Nations), cities are going to have get creative about ensuring their livability and cultivating open space where people can come together, move without the encumbrance of cars—and just plain “be.” By probing the full extent of their verticality and developing all three of their dimensions, cities can begin to find those places.

About the Author: Andy Cohen, FAIA, is Co-CEO of Gnesler, a global design and architecture firm. He participated in a panel discussion of what makes cities livable at the recent Milken Global Conference. Contact him at andy_cohen@gensler.com.

More from Author

Gensler | Apr 15, 2024

3 ways the most innovative companies work differently

Gensler’s pre-pandemic workplace research reinforced that great workplace design drives creativity and innovation. Using six performance indicators, we're able to view workers’ perceptions of the quality of innovation, creativity, and leadership in an employee’s organization.

Gensler | Mar 13, 2024

Trends to watch shaping the future of ESG

Gensler’s Climate Action & Sustainability Services Leaders Anthony Brower, Juliette Morgan, and Kirsten Ritchie discuss trends shaping the future of environmental, social, and governance (ESG).

Gensler | Feb 15, 2024

5 things developers should know about mass timber

Gensler's Erik Barth, architect and regional design resilience leader, shares considerations for developers when looking at mass timber solutions.

Gensler | Jan 15, 2024

How to keep airports functional during construction

Gensler's aviation experts share new ideas about how to make the airport construction process better moving forward.

Gensler | Dec 18, 2023

The impacts of affordability, remote work, and personal safety on urban life

Data from Gensler's City Pulse Survey shows that although people are satisfied with their city's experience, it may not be enough.

Gensler | Nov 16, 2023

How inclusive design supports resilience and climate preparedness

Gail Napell, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, shares five tips and examples of inclusive design across a variety of building sectors.

Gensler | Oct 16, 2023

The impact of office-to-residential conversion on downtown areas

Gensler's Duanne Render looks at the incentives that could bring more office-to-residential conversions to life.

Gensler | Sep 13, 2023

Houston's first innovation district is established using adaptive reuse

Gensler's Vince Flickinger shares the firm's adaptive reuse of a Houston, Texas, department store-turned innovation hub.

Gensler | Aug 7, 2023

Building a better academic workplace

Gensler's David Craig and Melany Park show how agile, efficient workplaces bring university faculty and staff closer together while supporting individual needs.

Gensler | Jun 29, 2023

5 ways to rethink the future of multifamily development and design

The Gensler Research Institute’s investigation into the residential experience indicates a need for fresh perspectives on residential design and development, challenging norms, and raising the bar.