Tracking the carbon footprint of higher education campuses in the era of online learning

By John Katzman, CEO, Noodle, and Elliot Felix, Founder, brightspot strategy, a Buro Happold Company

Universities are remarkable places that transform peoples’ lives. But neither their financial model nor environmental impact are sustainable.

With more effective use of their facilities, streamlining of administration, and thoughtful adoption of high-quality online learning, colleges and universities can raise enrollment by at least 30%, reducing their carbon footprint per student by 11% and lowering their cost per student by 15% with the same level of instruction and better student support.

Doing this, though, will take some work. We need to change how we think about growth, how we use space, and how we use technology.

First, we have shed the silicon valley narrative on the waning value of college and the doom and gloom fears from the coming demographic cliff. It’s tempting to see state governments dropping degree requirements for their jobs and Google’s plan for 20,000 career certificates as threats. Or assume decreased demand since 56% of Americans now think a four-year degree is a “bad bet.” But college provides an average of about a million dollars or more in additional lifetime earnings compared to high-school alone and 80% of college grads see an increase in salary sufficient to offset their tuition costs in under ten years.

Yes, there will soon be fewer 18-24 year olds entering college, but that doesn’t mean we need colleges less, it means we need less expensive colleges. Thirteen percent of Americans have some college credit but no degree; about half of those that left did so for financial reasons, down from 69% in 2018.

Second, college and university campuses are great assets but they are underutilized. Technical requirements will mean that new science buildings are needed periodically but classrooms, offices, libraries, and residence halls can be used more effectively rather than building new ones. The most sustainable building—financially and environmentally—is the one you don’t build.

Modest changes in how we use facilities could yield capacity to serve at least 30% more students in the same amount of space. Using classrooms five more hours per week at 5% higher utilization yields 20% additional classroom capacity.

Nationally, “work from home” has normalized at 30% of the work week. If colleges and universities adopted hybrid work aligning to that, this would save at least 20% space for the additional faculty and staff to teach and support the additional students. To be conservative, let’s assume we only achieve half of these efficiencies and gain 10% capacity to grow in place during the fall and spring. If each student enrolled one summer, that would yield about 10% more capacity on top of this. An additional 10% capacity can come from increased online learning, for a total of 30%.

Most importantly, all of these changes would improve most colleges in the eyes of both students and faculty. A third of on-campus students would like to see their colleges invest in online courses. While it may not be for everyone, fully online options continue to grow in popularity: both EDUCAUSE and Brightspot found about 20% of undergrads are looking for fully-online options, and there are now more students getting an MBA online than on campus. Sixty-nine percent of Dartmouth students gave high ratings to the summer semester. As for streamlining student services and academic support, that’s the quiet dream of every provost.

Third, better use of space and use of well-designed online learning can reduce the cost and carbon footprint of education. A mid-size public university spends about 25% on instruction, 10% on research, 20% on student support services, 20% on physical plant (including dorms), and roughly 25% on everything else including administration and operations. So, if a college or university increases enrollment online by 30% and keeps instruction and student support services constant, it can lower the cost per student by about 15%.

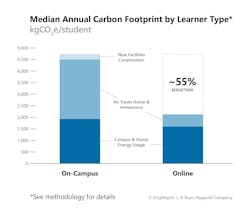

An online student has about half the carbon footprint of an on-campus student. If you compare the carbon footprint of two MBA students at top universities during a two-year program, an on-campus student will consume about 300 more kilograms of CO2 equivalent (kgCO2e) in stationary energy usage due to higher space needs and will consume about 2,000 more kgCO2e in air travel between campus and home and on global immersions.

The use of online learning and better use of current facilities avoids the construction of new facilities and their associated embodied carbon, the emissions from manufacturing, transporting, installing, maintaining, and disposing of building materials. In this case an additional 250 kgCO2e would also be avoided per student. Growing in place and online rather than building new space is critical since the built environment is responsible for 40% of global emissions considering the embodied carbon to build facilities and the energy to operate them.

The built environment is responsible for 40% of global emissions. Institutions must grow in place and online rather than build new space.

Since 2006, college and university presidents have committed to reduce their emissions and be more sustainable. Campuses have greened their infrastructure and increased their diversity. But most colleges and universities have added space faster than enrollment. Scholars such as Bryan Alexander have recently called attention to the impact of the climate crisis on higher education.

Now is the time to make education more sustainable—socially, economically, and environmentally. More effective use of space and thoughtful adoption of online learning can increase access to education, lower the cost per student, and reduce carbon emissions. Let’s get to work.

A brief note on methodology:

To compare the carbon footprint of online vs. on-campus learners, we considered MBA students in a two-year program and assumed 172 gross square feet per on-campus student based on the average of 15 top business schools. We also conservatively included 90 gross square feet for online students to account for faculty and staff office space, studios, and support space.

We assumed an 800 square foot apartment building off-campus, with on-campus students studying 35 hours a week on campus and 15 hours at home. To calculate emissions, we used Energy Star energy use data to estimate usage, assumed a 56.5% electricity and 43.5% natural gas split, and converted usage into emissions using EPA Emission Factors.

For travel, we assumed all online students take one trip to campus a year and that 75% of on-campus students travel to/from campus twice a year – 35% of those internationally. We also assumed that 32% go on a global immersion trip once over their two years based on websites of 20 top business schools. We estimated typical miles flown using the distribution of students relative to the distribution of institutions on a regional basis. Then we converted the miles flown to emissions also using EPA Emission Factors.

For embodied carbon savings, we used benchmarks from the Carbon Leadership Forum study to account for two years of savings over a building’s lifetime, assuming LCA Stage A embodied carbon for building structure, foundation, and enclosure for commercial office buildings.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

John Katzman is the founder and CEO of Noodle, which offers a series of technologies and services to make universities more resilient, responsive, efficient, and connected. Before that, he founded and ran The Princeton Review and 2U.

Elliot Felix is the founder of brightspot strategy, a Buro Happold Company. He has worked with more than a hundred colleges and universities to help students succeed with better facilities, support services, and technology, and he is the author of How to Get the Most Out of College.