I’ve served as the LEED coordinator on dozens of large projects since becoming a LEED AP in 2001. While it’s been a positive experience overall, there have been a few bumps along the way.

Recently, I jotted down those projects that really stuck out in my mind, and what I learned from them. I included some lessons passed on to me by my sustainability peers. After careful review, I’ve whittled this list down to my top 10 LEED lessons learned:

1. The LEED coordinator should be experienced with your project type.

The role of LEED and sustainable design must enhance, not compromise, a facility design. This especially applies to technical facilities, which one of my first LEED projects, a maximum security prison, happened to be. Being very eager to “green” this correctional facility, I aggressively encouraged the team to incorporate LEED-compliant sustainable features into the design.

While my heart was in the right place, it would have been more productive if I had first spent time learning how prisons work and then come prepared with sustainable concepts that could be accepted by the warden. For example, I was surprised to learn that some prisons actually allow "operable" windows--security fenestration units that allow inmates to regulate air flow through their cells--or that low-flush water closets pose a security risk due to the potential for increased maintenance required from from inmate vandalism. It’s not enough to just be experienced with LEED; experience with the project is also important.

2. Review LEED expectations during the pre-bid conference.

While today’s contractors are much more experienced, even comfortable with LEED, some don’t take enough time to evaluate their required LEED tasks when putting their bid together. One of the best ways to align proposals with a project’s LEED roles and responsibilities is to allow enough time during the pre-bid conference to go over the LEED requirements. This should include a brief review of relevant Division One specifications, the LEED scorecard, the submittal review process, and a stern reminder that each trade is responsible for LEED compliance that may not be expressly indicated in “their” spec division alone.

I learned this the hard way on a Dept. of Energy project, when a mechanical subcontractor used a noncompliant, high-VOC sealant on a fire-rated partition. No one thought to review their submittals for LEED compliance--even if the information on the sealant had been provided. The lesson learned is that a few minutes spent during the pre-bid conference should help reduce these types of oversights.

3. A picture paints a thousand words.

On more than one project I’ve discovered early in construction that no one was reviewing and tracking submittals for LEED compliance. Too often team members assume “the other guy is doing it,” especially with large, complex projects.

While the submittal review role is normally under the domain of the project architect, for some projects it often makes sense to have submittal review protocol and training specific to LEED. (The added complexities regarding materials and products in LEED Version 4 will make this even more critical.)

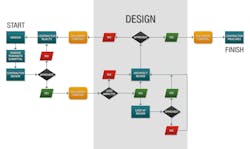

Over time, I’ve become absolutely convinced that the best way to communicate how submittals should be reviewed for LEED criteria is to distribute a project-specific flow diagram that shows how the submittals should circulate and where/when LEED review(s) occur. Creating this diagram is something I encourage each team to do early on. It still surprises me how often teams, especially design-build entities, have “disconnects” when it comes to reviewing submittals for LEED conformance.

Example of a clear submittals review process flow chart. This was for a design/build project.

4. Be very clear: Is LEED certification required or a goal?

Too many projects list a certain LEED rating level as a project “goal." Technically, this doesn’t compel the design and/or construction team to meet any level of certification. If a company or agency requires projects to earn a specific rating level, then this should be called a “requirement” in the project manual.

About a decade ago, I was brought into a LEED project at the beginning of construction and discovered there was a discrepancy between what the owner was expecting for the final LEED outcome and what the design-build team had edited in the contract. Achieving LEED Silver certification was originally listed as a “goal” in the agreement but, prior to signing, the design-build team had crossed out “Silver” and wrote in “Certified,” as they were not confident that Silver could be earned without excessive added costs. Fortunately, we did earn Silver certification and avoided any unpleasantries. But this contractual ambiguity left both parties exposed and was a gray cloud during the project, one that could have been avoided by changing just a few words.

5. Use a preliminary LEED scorecard in contract documents.

One of the best ways to guide a design and construction team as to which credits should be pursued is to provide a preliminary LEED Scorecard in the contract documents. This is normally included in Specification 018113 “Sustainable Design Requirements.”

This scorecard should state which credits or credit options the project must (and, in some instances, must not) pursue. However, unless there has been an in-depth LEED workshop with each credit carefully vetted, this scorecard should act as a guideline, informing the team of the parameters it should follow. It shouldn’t limit further exploration of sustainable opportunities without due cause.

6. Use established, robust specifications written for your project.

The importance of thorough, well-coordinated specifications that address the details of LEED cannot be overstated. Regardless of how the specifications are structured, it is imperative that the LEED AP and architect confirm the specifications are edited to apply to your project. (“Recycled” specs aren’t usually very sustainable!) And it’s important to ensure that bid documents have been reviewed and cross-referenced methodically to ensure the LEED information meets the “three ‘C’s of specifications": correct, complete, and coordinated. Failure to meet these criteria is costly to the design team, contractor, and owner.

7. Specify who pays for specialty consultants pertaining to LEED, and be sure their scope is well-defined in contract documents.

LEED requires project roles that in days gone by were considered “additional.” On an early nanotechnology project (back with LEED Version 2.0), it was not clear in the contract who was responsible to pay for energy modeling. The issue got kicked back and forth between the design team and the owner. Meanwhile, the project started and the design team did not have the benefit provided from early modeling information.

Finally, the mechanical engineer determined that they were able to absorb the cost in their fee and we were able to reduce the annual energy costs by more than 30%. It’s important that the contract agreement directly states who pays for such specialty LEED consultants.

8. Specify who pays for all GBCI fees.

Though the LEED certification fees paid to the GBCI are small in comparison to other project costs, if it isn’t clear upfront as to who pays these fees, the arguments that may follow can quickly waste more time, and thus money, than the cost of the GBCI fees.

A colleague of mine found this out with a large, not-to-exceed government project. The construction budget was more than $100 million, but because the issue of LEED certification fees was not addressed in the contract, far too much time was spent arguing over GBCI fees that totaled around $10,000.

Like so many aspects to LEED, being specific, especially early on, will save everyone time and money.

9. Specify criteria and expected outcomes for a front-end LEED/sustainable design workshop.

Many projects require a sustainable design workshop (aka, “eco-charrette”) or at the very least, a LEED scorecard review by the team. When including this deliverable in your RFP it is important to describe your expectations for the agenda, duration, facilitators, team members expected to participate, meeting location, and even who pays for food and drink, etc. I recall one workshop where the client was expecting the meeting venue to include coffee, which it did not. Emergency! A resourceful assistant found a nearby Starbucks and saved the day.

One critical component of the eco-charrette that is often overlooked is a report of the outcomes. Be very clear in your expectations. Is it just a preliminary LEED scorecard? Do you expect an analysis of the preliminary viability of each credit point? What about affiliated sustainability metrics like energy and water conservation goals and greenhouse gas emissions reduction, etc.? If you don’t describe in some detail what you are expecting, you may be disappointed with what you receive.

10. Don’t schedule the LEED plaque unveiling ceremony too soon.

Probably the most exciting LEED adventure I’ve had occurred right before a LEED plaque unveiling ceremony. Two nights before the ceremony we were distressed when the glass plaque had not yet arrived from the fabricator. (We ordered a custom-made glass plaque, back painted a particular hue of gold to perfectly match the project’s sustainability Learning Wall.) So, that evening I labored at a print shop trying to fabricate a “stand-in” plaque out of foam core and gold mylar. It wasn’t pretty.

Fortunately, the night before the ceremony the client rep. drove out to the airport UPS shipping distribution center and convinced them to look through their newly received inventory. Whew! It had arrived. (It was pretty. In fact, I’ve never been so happy to see a LEED plaque.) The ceremony the next morning went off without a hitch and everyone was pleased.

In retrospect, we should have given ourselves more time between the day we received our official e-mail award notification from the USGBC until the date we had scheduled for the ceremony. As it turns out, it can take several weeks for a standard plaque to be shipped to a team, and a custom one even more, as we painfully found out. Bottom line: give yourself plenty of time.

David Gibney is the Technical Director for Sustainable Design at M+W Group. He can be reached at: [email protected].