Sports teams get in the game: Mixed-use developments are using sports stadiums as their anchors

In the summer of 2020, the most expensive sports stadium ever built is scheduled to open in Inglewood, Calif., four miles from Los Angeles International Airport.

The 70,240-seat stadium on 60 acres will be home field for the Los Angeles Rams and Los Angeles Chargers pro football franchises. The facility would be expandable to 100,000 seats for mega events like the Olympics. And it will anchor the Los Angeles Stadium and Entertainment District (LASED), a redevelopment of the old Hollywood Park racetrack that’s being spearheaded by the Rams’ owner, developer Stan Kroenke, whose St. Louis-based Kroenke Group acquired the entire property in 2015.

The estimated cost of this privately financed complex has climbed to at least $5 billion. Plans for the district include 890,000 sf of retail space, 780,000 sf of office space, 300 hotel rooms, 2,500 residences, a 6,000-seat performing arts venue, a TV studio, restaurants, conference spaces, and 25 acres of public parks.

There’s little dispute that the LASED project—which dates back to 2005, when Stockbridge Capital Group purchased 238 acres in this downtrodden suburb—is the latest and most extravagant example of a sports team taking the reins of the funding, design, construction, and programming not only of a stadium or arena, but also the residential and commercial components around it.

As the price tags for their sports palaces escalate—and with taxpayer support for new arenas and stadiums tougher to muster—team owners and their banking and municipal partners are raising their bets on sports venues as catalysts for generating new revenue streams and for becoming the cynosure of their communities’ economic vitality. The Los Angeles stadium is setting the highest bar yet to test this premise.

Based on recent examples where sports-anchored mixed-use developments have flourished—most prominently The Battery Atlanta and Arlington Entertainment District in Texas—the key to success lies in assembling the right combination of building types and activities.

See Also: New ballpark is another draw for thriving downtown in Summerlin, Nev.

“We look at the mix of opportunities, but what’s more important is what can people do at those venues, and how they tie into the stadium or arena,” says Mark Williams, AIA, LEED AP, Principal and Director of Sports & Entertainment Business Development with HKS Architects, which designed Los Angeles Stadium at Hollywood Park. “Sophisticated ownership now understands that you have to capture audiences with a broader entertainment and time frame.”

Every sports project that Kansas City-based architectural firm Populous is working on “has some vision of mixed-use development,” says John Shreve, Senior Principal and Senior Urban Planner. “It’s what cities want.”

Sports teams kickstart development

Since at least 70 A.D., when the Coliseum in Rome was built, sports facilities have been part of their cities’ social fabric. More than a century ago, iconic ballparks like Boston’s Fenway Park and Chicago’s Wrigley Field were built to be centerpoints for their respective neighborhoods.

The relationship between sports teams and their communities has evolved over the past 50 years. And the connection became more strained as sports facilities migrated to the suburbs and became isolated from their fan bases.

Shreve of Populous points to three milestones:

• Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium, which when it opened in 1970 “was embedded within mixed use”

• Oriole Park at Camden Yards, which opened in Baltimore in 1992 and, says Shreve, established a new paradigm for an “extroverted” ballpark within an existing industrial sector of a city

• Sun Trust Park in the Cumberland suburb of Atlanta, which opened in 2017, and where the Atlanta Braves, working with JLL, led the development of an adjacent 1.2 million-sf mixed-use “micro neighborhood” called The Battery Atlanta.

Sports Business Journal estimates that, over the last 20 years, more than $12.2 billion in sports construction and renovation have anchored new entertainment development. It’s worth noting, too, that the Hollywood Park redevelopment in Los Angeles seemed to be stuck in neutral until Kroenke’s stadium proposal was approved and his company took over the project.

In the old development model, a stadium or arena would land, flying saucer-like, in an area, and the hope was that developers would follow and the neighborhood would benefit from new construction, jobs, business migrations, and tax revenue. But it hasn’t always worked out that way.

Logan Gerken, General Manager of Mortenson’s Sports + Entertainment Group, recalls how, decades after the Metrodome opened in 1982, that area of downtown Minneapolis was still mostly surface parking lots.

Now, “no one is leaving anything to chance,” says Gerken. The opening of the $975 million US Bank Stadium on the Metrodome’s site in 2016 coincided with a broader redevelopment—led by the city, Wells Fargo, and general contractor Ryan Cos.—of five blocks near the stadium that included 1.1 million sf of office space, 4.2 acres of parkland, 200 apartments, and a hotel.

Don Loudermilk, Senior Vice President and National Director of Sports for JLL, says that while the old development model can still be found in places like Denver, where the city is in the process of developing land next to Coors Field, it’s also increasingly common for teams to take more active roles in the development of what surrounds their stadiums or arenas.

In St. Paul, Minn., Mortenson is the master developer for a 25-acre mixed-use development near Allianz Field, the $250 million, 20,000-seat stadium that Mortenson is building for the Minnesota United pro soccer team, which is also involved in the development. The stadium is scheduled to open this spring. The master plan for the surrounding Midway neighborhood calls for one million sf of office space, 420,000 sf of retail and commercial space, 620 residential units, 400 hotel rooms, and 4,500 parking spaces. The build out is expected to take up to seven years.

Teams that get involved in development typically have several goals in mind. One is to create a district that’s programmed to attract visitors and customers year-round, beyond the team’s home schedule. “A lot of people don’t want to be inside the seating bowl but still want to be in the environment,” observes Williams of HKS. A sports venue needs to activate its area and provide alternatives that will appeal to those customers.

“We’re looking to create a 365-day attraction for Wisconsin residents that will help revitalize downtown Milwaukee,” says Peter Feigin, President of the Milwaukee Bucks NBA franchise. The team created a development company to purchase 27 vacant acres for a mixed-use revitalization around its $524 million, 714,000-sf Fiserv Forum, designed by Populous, which opened last August.

Fiserv Forum is a public-private partnership, with the Bucks’ current and former owners kicking in around $275 million.

But public financing for new arenas and stadiums is almost always a political hot potato, and more teams must foot the bill for their new homes themselves. It is in their financial interests to make sure that the streets around their facilities present a welcoming, safe, and fun atmosphere that, with greater frequency, incorporates live, work, and play components.

Technology cements the connection

There are certain elements that any new sports venue must have, says David Broughton, Research Director for Sports Business Journal. Street-level retail is one. A large plaza is another, preferably with an amphitheater or large electronic billboards where patrons can watch their team from several perspectives, or other events happening offsite simultaneously.

“It’s the venue that becomes the event, not just the ballgame,” explains Loudermilk.

Shreve points to the Populous-designed Kansas City Power + Light District, near the Sprint Center arena, which includes an area with huge screens that has come to be known locally as “The Living Room,” and attracts as many as 8,000 people at a time to watch different events.

As sports teams extend their reach beyond their home fields, technology helps connect them to customers and buildings within their districts.

“If I’m sitting at Texas Live! [the new bar and performance space at Arlington Entertainment District] or in a hotel, what else am I getting?” asks HKS’s Williams. “There needs to be layers added on.” He notes that teams can alert customers to what’s going on at the Entertainment District via those customers’ smartphones.

Is the investment worth the cost?

The economics of sports is such that teams must constantly look for ways to monetize their assets, be they players or buildings. Rick Welts, President and COO of the NBA’s Golden State Warriors, is on record stating that because his team’s new billion-dollar, 18,000-seat Chase Center, which opens in September, is being financed without tax subsidies, it was imperative to include within the 11-acre arena district 100,000 sf of space for 29 retail locations. The Chase Center also will include 580,000 sf of office space in which Uber will be the primary tenant and own 45%, with the Warriors owning 45% and Alexandria Real Estate Equities 10%.

The Warriors have proposed building a 142-key hotel with 25 condos on Chase Center’s campus. And next year, its plans call for the addition of a 3,000- to 5,000-seat performance venue. When completed, Chase Center will host at least 200 events a year.

That’s great for the team, but what about the city? What will be the ultimate economic impact of a venue like Chase Center, or Fiserv Forum, or Los Angeles Stadium at Hollywood Park?

That question has long been at the heart of the debate about cities providing subsidies to sports teams for new arenas or stadiums. Despite claims by teams and their advocates that new facilities more than pay for themselves, a 2017 poll of economists found 83% agreed that the cost-benefit was rarely in a city’s favor (bit.ly/2T5Z4yx).

It’s too early to speculate on what the LASED will deliver. But there’s telling anecdotal evidence of sports-anchored entertainment districts that have altered their neighborhoods’ futures.

One of these is the bustling 2,018-acre Entertainment District in Arlington, Texas, a once-sleepy city between Dallas and Fort Worth best known for its Six Flags Over Texas amusement park. This district—which straddles the 100,000-seat, $1.3 billion AT&T Stadium, home of the Dallas Cowboys, which opened in 2009—was a central element of Arlington’s 2014 Strategic Plan to transform this city into a business and entertainment destination.

Last September, the $250 million, 200,000-sf Texas Live!, with its 5,000-person-capacity outdoor event pavilion, opened there, another box checked in the district’s $4 billion master plan. Over the next few years, the district will also realize a $150 million, 302-key Loew’s hotel and event center; and the $1.1 billion, 40,000-seat Globe Life Field, the new home for the Texas Rangers (an investor in the district).

Last November, the 100,000-sf Esports Stadium Arlington opened within the city’s convention center. With capacity for 2,500 spectators, it is the largest eSports stadium in the world.

A second noteworthy example of a sports-driven development is Sun Trust Park, the $672 million, 41,000-seat home of the Atlanta Braves, which opened in 2017. The Braves, owned by Liberty Media, also contributed $400 million and acted as a development partner for the 80-acre mixed-use district surrounding Sun Trust Park, called Battery Atlanta. (The Braves developed Sun Trust Park and Battery Atlanta with Cobb County, Ga., which issued nearly $400 million in bonds for this project.)

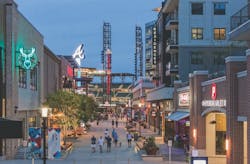

The team is the majority owner of Battery Atlanta, which includes a nine-story office building that serves as Comcast’s headquarters, 350,000 sf of retail and restaurant space (it will eventually have 60 restaurants), a 264-key Omni Hotel, a 550-unit apartment complex, and the 3,500-seat Coca-Cola Roxy Theater.

JLL conducted a feasibility study to assist the Braves and the county in locating the ideal property for this development, and to identify the right mix of buildings. (It found, for example, that the area was underserved by retail and multifamily.)

Last fall, the Center for Economic Development Research, a unit of Georgia Tech’s Enterprise Innovation Institute, did an analysis of the economic impact of the ballpark and district (bit.ly/2C7PHUH). It calculated a net fiscal impact for the county of $18.9 million per year over a 20-year period.

While the ballpark’s revenue was expected to fall short of covering the county’s debt service, maintenance, and operating costs by about $7.4 million per year, Battery Atlanta’s annual revenue to the county’s government and schools would exceed annual expenses by approximately $12 million.

The study also factored in the “halo effect” from the impact of SunTrust/Battery Atlanta on property that’s near this complex. The study calculates that tax revenue from those properties would exceed county expenses by $12.7 million.

Loudermilk was in Atlanta over the Christmas holidays, and witnessed full restaurants everywhere at Battery Atlanta. “It has become a place to go, especially for Millennials.”

Indoor and outdoor redefined

Debates about financing notwithstanding, sports-anchored development continues to march forward, with projects either proposed or under way in Buffalo, N.Y., Harrison, N.J., Hartford, Conn., Tampa Bay, Fla., Washington, D.C., and Oakland, Calif., to name just a few (see sidebar).

Sometime this year or early 2020, construction will begin on Mission Rock Pier 48, a 28-acre mixed-use neighborhood in San Francisco that, when completed in 2025, will include between 1.3 million and 1.7 million sf of commercial space, 750,000 to 1.5 million sf of residential, 150,000 to 200,000 sf of retail, and 850,000 sf of structured parking. The project’s lead developer is the San Francisco Giants. Mission Rock is projected to generate more than $25 million annually in new revenue for city services.

“As long as these districts respond to the experiences of their patrons, there’s something about these buildings that are memory-making, and bound us together,” says Williams.

And the concept continues to evolve. Shreve says Populous is designing a sports project in Southern California that, if realized, could include popup venues for retail and entertainment, as well as spaces for X-Games and eSports, whose customers “are growing by leaps and bounds.”

Mortenson’s Gerken thinks the next iteration of mixed-used sports will offer more in-venue access to clubs and hospitality, and “blur the lines between the indoor and outdoor” of the arena or stadium.