Shape shifters: Kinetic architecture allows buildings to perform beyond their intended purpose

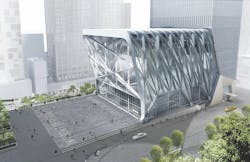

On Manhattan’s West Side, adjacent to the 26-acre Hudson Yards commercial redevelopment, a 200,000-sf cultural and arts center under construction is one of the latest—and, at $435 million, priciest—demonstrations of the practical and aesthetic value that kinetic architecture can bring to an ambitious project.

The Shed, as this center is called, should be completed by late 2018, with a spring 2019 grand opening scheduled. Designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R) in collaboration with Rockwell Group, the building’s 170,000-sf permanent structure features eight stories of museum, exhibit, education, and performance spaces.

Its back-of-house spaces—for offices, dressing rooms, mechanical equipment, and storage—are on level one and the lower levels of 15 Hudson Yards, a residential tower to the west. This structural integration allows the bulk of The Shed’s base building to be programmable.

The Shed’s calling card is its 8.9-million-lb, 115-foot-tall movable shell that, when fully opened, will add 17,000 sf of light-, sound-, and temperature-controlled multipurpose space. When fully retracted into the building, it will uncover an open-air public plaza.

Kinetic architecture allows parts of a building to operate independently without altering the structural integrity of the building. The concept is as ancient as drawbridges in the Middle Ages, and as timely as building exterior schemes that adjust to natural elements. In fact, The Shed’s lineage, say its designers, is traceable to Fun Palace (1964), Cedric Price’s socially interactive machine concept that would adapt to time and place.

While it’s still a niche, demand for buildings with kinetic features “is definitely rising,” says Kevin Smith, Director of Product Applications and Development with Pittsburgh, Pa.-based manufacturer Extech. Smith spoke about kinetic façades at Greenbuild last November.

“The trend is to apply kinetics so the building can be used for more than one thing,” says Thomas Duffy, PE, Associate Principal with Thornton Tomasetti in New York, which is in charge of The Shed’s structural design, façade engineering, and kinetic engineering services.

A few years ago, Thornton Tomasetti helped simplify the movement and activation of hydraulic-mounted aluminum louvers that architect Santiago Calatrava had designed to provide solar shading for the $60 million Innovation, Science, and Technology Building at Florida Polytechnic University, in Lakeland.

Another Calatrava project regularly crops up in conversations about kinetic architecture: the Quadracci Pavilion for the Milwaukee Art Museum, completed in 2001. The architect designed the pavilion with a movable, 217-foot wingspan that opens by day and folds over the building at night or during bad weather.

More experiential than performative

But why kinetics? What purpose does a movable component serve—other than calling attention to itself—for a building and its occupants? Is kinetics worth the cost and complexity? Does it require more maintenance?

All of these are questions that AEC firms and their clients ask when considering kinetic options in design and construction.

Until recently, kinetic architecture was more prevalent in Europe because of higher energy costs there and clients wanting to maximize daylighting, explains Mehrdad Yazdani, Design Principal and Yazdani Studio Director for CannonDesign in Los Angeles.

“The concept of articulated façades goes back to 2003, and a lot of work was done in England,” adds Matt Fineout, Design Leader in CannonDesign’s Pittsburgh office. “Back then, systems were more mechanically operated. Now, polymers with ‘memory’ take different shapes upon contact with heat, cold, water; and then return to their original shape.”

Duffy attributes greater interest in kinetics among U.S. developers and AEC firms, in part, to technological advances in control systems that stem from fields outside of construction. The Shed’s movable shell, mounted on six steel wheels (each six feet in diameter) that roll on tracks, is powered by a dozen 15-hp motors that drive a gantry crane borrowed from the shipping and rail industries.

It seems, though, that the rationale for kinetic design in the U.S. is as much experiential as performative, observes Anne-Catrin Schultz, PhD, Assistant Professor at Wentworth Institute of Technology’s College of Architecture, Design, and Construction Management, who also spoke at Greenbuild about kinetic façades.

She points, by way of example, to the “dynamic” façade system for the 10-story, 68,800-sf parking garage at Logan Airport in Boston, which opened in 2016. That façade consists of 48,000 aluminum flapper panels that move in response to wind currents. The six-inch-square curved panels are set within 353 extruded aluminum framing support assemblies that span eight stories high by 290 feet wide.

“Kinetics provide architects with an added palette element,” says Smith, whose company manufactured the flappers, and subjected them to 130-mph wind tests.

A more spectacular demonstration of experiential kinetics can be found at OMNIA, a $107 million nightclub, also designed by Rockwell Group, which opened inside Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas in 2015. The centerpiece of the club is a 13,000-lb spaceship-like chandelier with eight concentric composite rings ranging from three to 32 feet in diameter. Within the chandelier’s grid are 21 winches that allow the rings to move through space and descend closer to the dance floor. The fixture’s lighting system includes 20,152 individual tri-color LED pixels.

“The purpose of the chandelier is to change the energy in the room,” says Tyler Kicera, Senior Director of Business Development for TAIT Towers, the engineer and contractor for the chandelier. It was designed by noted set designer Willie Williams, in collaboration with Shawn Sullivan, a Partner at Rockwell Group.

A practical alternative

Kinetic architecture is often associated with glitzy, one-off projects and major price tags. But in recent years the practical, even economical, application of kinetics to enhance a building’s utility and performance has become at least a more viable alternative to be considered.

Smith of Extech notes that a kinetic system for lighting and air controls that his firm built recently for a cloud service center in North Carolina replaced mechanical systems that would have added considerably to the project’s cost.

Uni-Systems is best known for its Enfold retractable canopy systems, which the company launched in 2012. Its product line has had a lot of interest, in particular from restaurants that want to expand their bookable spaces year round. “Some restaurants that installed Enfold five years ago are coming back for larger systems because they know they will pay for themselves in a few years,” says Uni-Systems’ Vice President Peter Fervoy.

One of the more heralded illustrations of kinetics contributing to a building’s performance is the 145-meter-tall Al Bahar Towers development in Abu Dhabi, which opened in 2012. Its responsive façade includes a shading system developed by the computational design firm Aedas Architects, which created a screen that sits two meters outside of the building’s exterior and acts as a curtain wall. The screen’s triangular, fiberglass-coated panels are programmed to respond to the sun’s movement to reduce heat gain and solar glare during the day.

That system helps lower the building’s heating and cooling expenses by 50%, according to Nassim Saoud, a Director with Gehry Technologies, in Paris, which worked on the project as a technical advisor.

CannonDesign went further with a design concept it developed with Arup for the 1.2-million-sf, three-tower CJ Blossom Park in Gyeonggi-do, South Korea. Yazdani explains that the original concept called for wrapping the exterior façade with an aluminum scrim of curved, perforated panels that moved based on the amount of sun or clouds outside. Embedded into certain areas of the scrim would be “apertures” that open by as much as 10 feet.

The project team had to drop the scrim’s operability component, however, because the mechanical engineers on the project couldn’t provide the client, CJ Corp., with long-range energy cost savings data—compared to the $10 million initial cost of the wall system—within the project’s construction timeframe. The irony, Yazdani notes, is that the data bore out the concept’s efficiencies.

Making tight spaces work better

Cost is always a factor in assessing the efficacy of kinetic architecture, and not always the way one might suppose.

Take the much-ballyhooed U.S. Bank Stadium in Minneapolis, which opened in 2016. Its owners wanted to bring in the outdoors with a retractable roof, and the project’s architect, HKS, was ready to give it to them.

But Thornton Tomasetti, the project’s SE, suggested instead a roof made from the plastic ETFE that’s 60% clear and would require less structural support. Because of its low R-value, snow that makes contact with the roof would melt quicker. Thornton Tomasetti also recommended the installation of a 95x200-foot door at the west end zone that, when opened, lets the outdoors in.

By taking this advice, the owners saved somewhere around $200 million, Duffy estimates.

The project team for The Shed in New York will clad the building’s shell with ETFE, which has the same insulating properties as glass, but 1/100th the weight, says Robert Katchur, Associate and Project Manager with DS+R.

Elizabeth Diller, a Founding Partner at DS+R, says that including a movable shell in this building was the result of the team’s determination that projecting what the art world and the economy would look like in 10 to 15 years was unknowable, so The Shed needed to be designed with the utmost flexibility.

However, opting for a kinetic solution was also borne out of necessity: In its redevelopment plan for Hudson Yards, the Hudson Yards Development Corporation, which issued the project’s RFP, allocated only 21,000 sf over the West Side Railyard for cultural use. The lot selected, on the southeastern side of the railyard, was combined with an adjacent 20,000-sf parcel for The Shed.

“The footprint demanded a compact solution, and the shell part of the building can be used when needed, or nested when it isn’t needed,” says Evan Tribus, Senior Associate and Project Manager with Rockwell Group.

The building is designed to achieve LEED Silver certification, and to exceed New York’s energy codes by 25%, which is required of all new buildings on city-owned land or using city-provided funds. Despite the shell’s massive two-million-cubic-foot interior, only the lower 30% will need to be temperature controlled. And the plaza will include a radiant-heat floor plate.

Tribus and Katchur agree that the intuitions about this project held by Diller and Rockwell Group’s Founder and President David Rockwell, FAIA, which date back to 2007, turned out to be prescient. The only major change in the design was to position the building along an east-west axis (as opposed the original north-south plan), so that The Shed would run parallel to the popular High Line promenade.

“It wasn’t our intent to fetishize kinetics, but to use it at the service of the building’s programming,” says Tribus. For example, when the hall inside of the shell merges with the adjacent gallery at the Plaza Level of the permanent building, it creates 30,000 sf of contiguous space, which would be one of the largest galleries in the city.

“I believe this building, as a piece of architecture and as it unfolds over time, will inspire artists’ imaginations,” says Tribus.