City services buildings such as police and fire stations, libraries, city halls, and medical examiner’s offices are important touchpoints for the communities they serve. In some respects, they define the character of the government and color the interactions between citizens and public servants. One of the main architectural challenges of designing buildings for the public sector is designing buildings that embrace the community through their public-facing functions while maintaining the security, functionality, and financial stewardship expected by administrators and taxpayers.

In this article, I’ll share insights from some recent LEO A DALY projects that blend the unique program requirements of high-performing city governments with prominent community functions of beloved civic architecture.

Degrees of transparency

Blending the public and private functions of a highly secure, highly visible city department is a fundamental challenge of civic architecture. Many projects err on the side of security, resulting in facilities that feel imposing and unwelcoming. A more nuanced design approach looks for opportunities to create transparency, offering a more welcoming curb presence that integrates passive security features.

The Omaha Police Department’s Elkhorn precinct, now under construction, serves as home base for SWAT team, traffic patrols, and detective work in the western suburbs of Omaha, Nebraska. It also functions as a hub for public-focused activities such as community meetings and televised press conferences. This dual role inspired a design that is both secure and inviting – keeping officers safe while looking great on TV.

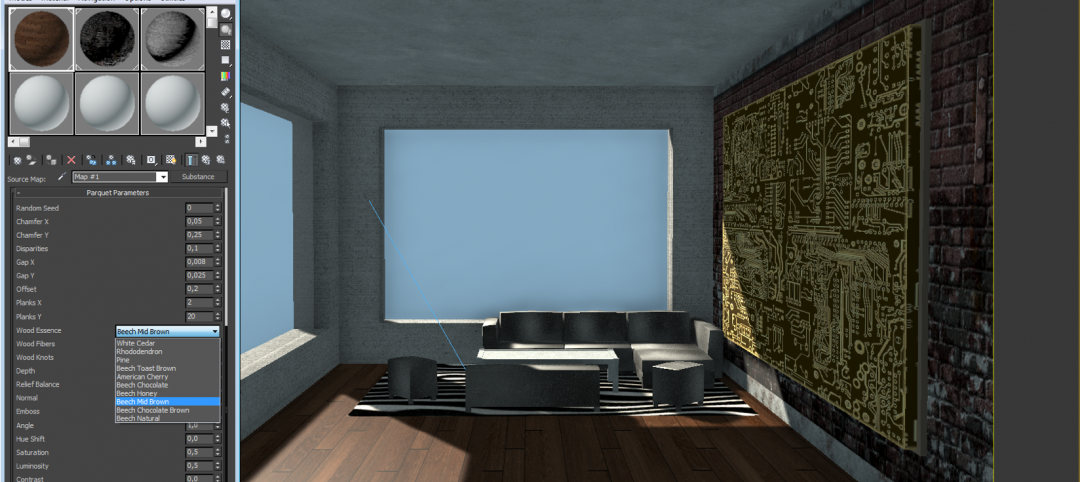

At the outset of design, we conceived of the building program as comprising two functional zones – public and private – that are reinforced through the expression of material and form. Public spaces are distinguished by wood and glass, while private spaces use a more utilitarian language of introverted brick and metal-clad masses with strategically located window openings. The design also uses landscaping and different levels of separation or transparency to reinforce the contrasting functions of the building’s different zones.

The station is foregrounded by a sort of mini park that doubles as a passive security feature. Inviting bench seating and short concrete walls at varying heights offer a place to eat lunch or chat, while also protecting the building from vehicular ramming. The roof line of the building, with its dramatic upward sweep and warm wood soffit, is a gesture of invitation to community. The soffit flows from the exterior to the interior, forming the ceiling of a large community room. This volume is enclosed by a façade of brick on the lower half and clerestory above, presenting a solid but transparent face, and allowing natural light to fill the space.

Beyond the reception desk, the building becomes gradually more security-forward, with offices, training space, traffic patrol office, and the SWAT zone. Windows are limited to a narrow horizontal band, allowing some natural light to enter without compromising security. Police parking occurs beyond a secured perimeter set back from the public front of the building.

A meaningful public image

Some municipal complexes co-locate multiple services in one large building – great for efficiency and convenience, but with a risk of creating a monolithic government presence. Thoughtful architecture can help citizens differentiate among the various government functions, improving public image and creating new opportunities for community engagement.

An existing municipal complex in Oakdale, Minnesota, was running out of room for the police, tax assessor, city hall and council chambers that were housed there. The addition of a new indoor training facility, squad car parking garage and administrative zones gave us the opportunity to reimagine the face of the department by reimagining its city services building.The station, located adjacent to the park, is set off with a memorial to a fallen officer at one of the main park entries, transformed how the public views and interacts with the police department.

In the existing municipal complex, the police station did not stand out from the other functions, resulting in an anonymous, overbearing architectural presence. Our planning study for the addition involved digging into the history of the department and its neighborhood context. Through this process, we saw a chance to use architecture to highlight the police function and underscore the importance of its mission.

The police addition is situated on the edge of a public park named after Richard Walton, an Oakdale police officer who was off duty when he was killed in the act of preventing a crime in 1982. To highlight that piece of civic history, we integrated a memorial plaza into our design between the park and the police station. With this gesture, the police department reaches out to the public, and gives visitors to the park an opportunity to reflect on the role of police in the community. Together with a new charcoal-colored concrete façade, the memorial identifies the police station and adds depth to the department’s image.

Architecture of recruitment

Beyond providing a functional response to space needs, civic architecture also serves as a city’s most permanent and prominent billboard and storytelling tool. Thoughtful design allows cities to leverage their buildings to communicate strategic messages in a powerful way.

One small Minnesota town engaged LEO A DALY to design a new station for its all-volunteer fire department. As an all-volunteer force, the department is in perpetual need of new recruits. This need inspired a design concept that creates, in effect, a micro-museum within the station, where the the collected historical artifacts of a hundred years of volunteer fire fighting are displayed as a public recruitment tool.

The station is situated at a prominent roundabout on the town’s beloved trail and park network. Taking advantage of this location, the proposed design creates a pocket park at this intersection. Landscaping creates a rest area and water-filling station, where cyclists and runners can take a break. A transparent façade allows passers-by to look in on historic helmets, a 1920s fire truck and other artifacts. At night, the space is illuminated, creating a lantern effect.

Seeing history on display in such an inviting setting would build good will for the fire department among multiple generations of potential volunteers.

A measure of comfort

On the surface, some municipal building types do not lend themselves to engagement with the community. The medical examiner’s office, for example, is mostly composed of windowless lab space for conducting medical investigations. However, the small public spaces that are part of a medical examiner’s facility serve an outsized role in community engagement. Designed well, they help cities show a caring face and make a difference in the lives of citizens.

The public areas of a medical examiner’s office are unique among civic spaces. They host citizens on what might be the worst days of their lives. Bereaved people arrive with the unenviable task of identifying a body – often that of a loved one. They enter in an emotionally vulnerable state, possibly in shock, and certainly with a high level of anxiety. The design of these areas requires a delicate, compassionate hand.

The Hennepin County Medical Examiner Facility is designed to offer members of the public a measure of emotional comfort in the midst of hardship. Beginning with the landscape, visitors are surrounded by nature, shepherded toward the front door by a short retaining wall evokes a memorial. Copper overhanging the entrance and wooden detailing immediately bring a sense of warmth to the visitor and signify entry. Upon entering the lobby, the visitor’s views are reoriented to the exterior, toward a specimen oak tree. Waiting room seating looks out on this tree, growing amid a field of native grasses, creating a moment of quiet contemplation in an otherwise stressful process.

At its simplest level, a city provides a service. The better public servants can connect with the people they serve, the better the community will function. Architecture facilitates those connections in many ways – by giving city governments a physical identity, by creating inviting settings for citizens to participate in public life, and by communicating, in ways big and small, the values we live by. The designer’s fundamental role is to deliver a functional, efficient facility, but it goes beyond that. Our real challenge is to deliver more value without adding more cost, creating spaces that embrace, and are embraced by, the communities that fund and use them.

Related Stories

| Dec 17, 2010

Arizona outpatient cancer center to light a ‘lantern of hope’

Construction of the Banner MD Anderson Cancer Center in Gilbert, Ariz., is under way. Located on the Banner Gateway Medical Center campus near Phoenix, the three-story, 131,000-sf outpatient facility will house radiation oncology, outpatient imaging, multi-specialty clinics, infusion therapy, and various support services. Cannon Design incorporated a signature architectural feature called the “lantern of hope” for the $90 million facility.

| Dec 17, 2010

Cladding Do’s and Don’ts

A veteran structural engineer offers expert advice on how to avoid problems with stone cladding and glass/aluminum cladding systems.

| Dec 17, 2010

5 Tips on Building with SIPs

Structural insulated panels are gaining the attention of Building Teams interested in achieving high-performance building envelopes in commercial, industrial, and institutional projects.

| Dec 17, 2010

How to Win More University Projects

University architects representing four prominent institutions of higher learning tell how your firm can get the inside track on major projects.

| Dec 13, 2010

Energy efficiency No. 1 priority for commercial office tenants

Green building initiatives are a key influencer when tenants decide to sign a commercial real estate lease, according to a survey by GE Capital Real Estate. The survey, which was conducted over the past year and included more than 2,220 office tenants in the U.S., Canada, France, Germany, Sweden, the UK, Spain, and Japan, shows that energy efficiency remains the No. 1 priority in most countries. Also ranking near the top: waste reduction programs and indoor air.

| Dec 7, 2010

Are green building RFPs more important than contracts?

The Request for Proposal (RFP) process is key to managing a successful LEED project, according to Green Building Law Update. While most people think a contract is the key element to a successful construction project, successfully managing a LEED project requires a clear RFP that addresses many of the problems that can lead to litigation.

| Dec 7, 2010

Blue is the future of green design

Blue design creates places that are not just neutral, but actually add back to the world and is the future of sustainable design and architecture, according to an interview with Paul Eagle, managing director of Perkins+Will, New York; and Janice Barnes, principal at the firm and global discipline leader for planning and strategies.

| Dec 7, 2010

Green building thrives in shaky economy

Green building’s momentum hasn’t been stopped by the economic recession and will keep speeding through the recovery, while at the same time building owners are looking to go green more for economic reasons than environmental ones. Green building has grown 50% in the past two years; total construction starts have shrunk 26% over the same time period, according to “Green Outlook 2011” report. The green-building sector is expected to nearly triple by 2015, representing as much as $145 billion in new construction activity.

| Dec 7, 2010

USGBC: Wood-certification benchmarks fail to pass

The proposed Forest Certification Benchmark to determine when wood-certification groups would have their certification qualify for points in the LEED rating systemdid not pass the USGBC member ballot. As a result, the Certified Wood credit in LEED will remain as it is currently written. To date, only wood certified by the Forest Stewardship Council qualifies for a point in the LEED, while other organizations, such as the Sustainable Forestry Initiative, the Canadian Standards Association, and the American Tree Farm System, are excluded.