Owners, developers, and AEC firms regularly espouse the virtues of early project collaboration. But few teams have been willing to check their egos and financial prerogatives at the door in order to enter into true integrated project delivery (IPD). IPD is the ultimate collaboration, where signatories are contractually obligated to work together from a project’s start to its finish, to solve problems jointly, and to put their money where their mouths are by placing some of their profit margin at risk based on achieving predetermined cost targets.

These agreements, when executed properly and fully, have proved to be beneficial to owners’ and building teams’ bottom lines. For example, outpatient clinics that Advocate Health delivered in 2016 and 2017 under IPD contracts with eight AEC partners achieved $12.5 million in savings, or 12% below those projects’ $103.5 million target cost—which itself was $23.1 million less than the $126.6 million budget that Advocate had initially approved for these clinics’ construction.

See Also: Developers invest in mega amenities to draw top-notch tenants

IPD, though, should not be misconstrued as value engineering, as it can actually expand a project’s scope of work. Last May, Brown University held a formal dedication for its new $88 million, 80,000-sf Engineering Research Center on the school’s Providence, R.I., campus. Brown built the center under an IPD contract that included Kieran Timberlake (designer), Buro Happold (engineer), Shawmut Design and Construction (GC), and 15 trades. (This was a first IPD project for all of the signatories, and each put some profit at risk.) The team completed the building project three months ahead of schedule, and in the process added about $11 million to its scope, according to Mark Davis, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, Principal with Kieran Timberlake.

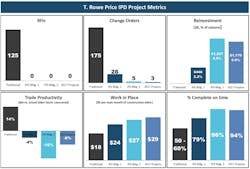

Compared with a traditional delivery method, IPD has led to considerable improvements in reducing change orders and producing productivity. T. Rowe Price has invested savings back into its projects. Courtesy T. Rowe Price.

“It’s a beautiful building whose design would have been harder to sell under a strict dollars and cents contract,” says Davis.

Other AEC firms that have signed onto IPD agreements also say their rewards aren’t just monetary. “The goal of the project always comes first, and it’s a lot more pleasant experience,” says Scott D. Bulera, Vice President and General Manager for Turner Construction’s Baltimore office. From 2012 through October 2018, Turner had entered into 66 IPD contracts with total values of $1.4 billion.

But IPD remains an exception to other preferred delivery methods. One reason is that the contracts generally aren’t structured for competitive bidding, which government projects require. Some owners either don’t see a problem that needs fixing or don’t want to relinquish project control. Insurers aren’t always comfortable with an IPD’s shared risk. And prospective signatories fret about confidential information leaking outside the contract.

IPD must overcome “a legacy of procurement and law” that resists the level of transparency and trust that these contracts demand, says George Zettel, Turner’s North America Program Manager for Integrated Project Delivery and Lean Operations/Transformation. He notes that some attorneys still believe their owner-clients fare better by transferring risk to AEC firms, despite the fact that 70% of all projects come in over budget and late.

“We call this the definition of insanity,” says Zettel.

IPD also needs champions who keep the owner and signatories enthusiastic about the contract. At the investment firm T. Rowe Price, which currently is engaged in a nine-building renovation IPD contract with seven AEC and supplier firms, that person has been Brian Dean, the company’s Head of Corporate Real Estate and Workplace Services. Dean, along with Charles Nugent, T. Rowe Price’s Manager of Construction and Project Management, spent a year learning about IPD, an education that included reading the influential book “Commercial Real Estate Revolution,” to which three eventual contract signatories—Turner, Gensler, and furniture supplier Haworth—contributed. Dean also spent a lot of time getting his company’s legal and procurement departments on board. “Unless the owner is motivated, these contracts won’t happen,” says Turner’s Bulera.

Dean’s efforts were supported by Jim Camp, AIA, LEED AP, Design Manager and Principal with Gensler, who was instrumental in assuaging his firm’s anxiousness about this IPD contract’s fee-at-risk component.

Tailor-made for medical centers

Several sources note that IPD seems best suited for repetitive projects whose design, engineering, and construction/renovation are similar, building to building.

IPD also generates the greatest value when it’s connected to highly complex, high-risk projects, whose nature requires team investment and problem solving, says Robert Mitsch, Vice President of Facility and Property Services at Sutter Health, an early IPD adopter.

Sutter has delivered nearly $2.1 billion in projects executed under IPD contracts, and has another $2.5 billion in the works. Across 24 projects completed under IPD contracts, Sutter has saved an estimated $220 million, says Mitsch.

“It is a tremendous delivery method,” adds Digby Christian, Sutter Health’s Director of Integrated Lean Project Delivery. One of its recent projects is Van Ness and Geary Hospital in San Francisco, a 15-story, 274-bed acute care facility that’s scheduled to open in March. There were three signatories to that project’s IPD contract, including SmithGroup (designer) and a partnership of Herrero Builders and The Boldt Company (GC). Fourteen trades put some of their profit at risk under IPD subcontracting contracts.

Advocate Health Care began its journey toward IPD in 2008, when it started pushing lean and modular construction practices. Its investigation into this delivery method got serious in 2013-14, when Advocate started rolling out ambulatory outpatient clinics and anticipated at least $300 million in construction costs. At the same time, Advocate stated its commitment to driving down total construction costs by 20% by 2020, says Scott Nelson, Advocate Health Care’s Vice President of Planning, Design, and Construction.

The health system’s first Integrated Lean Project Delivery contract included an architect, engineer, and GC, and delivered seven clinics. Advocate then came up with its first national Master ILPD agreement that involved 29 (now 31) AEC firms and subcontractors. Eight of these firms—HDR (architect, interiors, landscape), IMEG (MEP, technology), Boldt (GC, cost estimating), and trade partners Martin Petersen, Glass Solutions, Huen Electric, LeJeune Steel, and framing/drywall subcontractor The Rockwell Group—are members of Advocate’s Ambulatory Collaborative that work together as a team and put some of their profit margins on the line.

Here’s how that contract works: Each project has an allowable budget that Advocate’s board approves. The company and the collaborative then agree on a target cost with reduction goals. The difference between the budget and target constitutes the contract’s incentive compensation layer. Advocate keeps 50% of the savings achieved below the target cost, and the signatories split the other half, based on the scope of their work and the portion of their profit each contributes to the risk pool.

“I admit, I was skeptical about the target goals,” recalls Jeff Neisen, Boldt’s Group President–Central Operations. “But I give credit to Advocate for setting them upfront. The contract empowers the partners to meet them.”

Advocate Medical Group and eight AEC firms are signatories to an Integrated Lean Project Delivery contract, in which each puts a portion of its profit margin on each project at risk, and splits what savings the team achieves below an agreed-upon target cost.

EYE-OPENING RESULTS FOR ADVOCATE

As of last October, 17 projects had been completed under Advocate’s ILDP contracts, including 10 projects in 2017 alone. The results have been impressive:

• In 2017, the Ambulatory Collaborative achieved 14% cost savings (compared to Advocate’s corporate goal that year of 10%). Five of the 10 projects achieved savings between 16% and 28%.

• 20.3% of the 10 projects involved modular construction (compared to a 20% goal), with four projects at 27% or higher.

• These contracts are learning experiences for their participants. One of the first projects the Ambulatory Collaborative tackled was a 44,000-sf clinic in Libertyville, Ill., which took 33 weeks to complete in June 2016. The collaborative took only 23 weeks to complete, in August 2018, a 44,478-sf reconstruction of a former Sports Authority and connected parking garage on North Clark Street in Chicago.

“We’ve found that putting skin in the game brings these contracts to another level,” says Mike Doiel, HDR’s Senior Vice President. “People do things on IPD projects that aren’t normal; they look out for each other. There’s almost zero change orders and much smoother conflict resolution. I don’t know why you’d do a project any other way.”

Five of the 17 projects, including North Clark, were completed under an Integrated Form of Agreement (IFOA), whose signatories risked 100% of their profits toward hitting the project’s agreed-upon target cost. The Ambulatory Collaborative meets every Wednesday to keep projects on track toward reaching their goals.

Advocate originally envisioned building around 30 clinics using IPD methods, but after Advocate merged with Aurora Health Care in April 2018, that number could get as high as 50. Doiel confirms that a dozen new clinic projects in Wisconsin are scheduled to release starting this month, most of them under IFOAs.

The 10 Advocate Medical Group projects completed under an Integrated Form of Agreement in 2017 achieved an aggregate 14% savings.

Finding the right balance

T. Rowe Price’s Dean and Nugent recount how their company got interested in IPD: It was purely out of frustration with a budgeting process that was “pulling a lot of scope out of projects” only to have them come in under budget, says Dean. “We knew we could do better.”

Its first multi-party agreement was for a $21 million renovation of the company’s 105,000-sf Building 1 on T. Rowe Price’s headquarters campus in Owings Mills, Md. “A complete gut,” recalls Bulera of Turner, the GC on the project, which started in July 2014 and took about seven months to complete (including preconstruction and design).

During the second renovation of the 108,000-sf Building 2, T. Rowe Price converted its multiparty contract to an IPD master agreement with project-to-project authorization, says Bulera. The other signatories were Gensler (design architect), TAI Engineers (MEP design engineer), Poole & Kent (ME), M.C. Dean (EE), Haworth (furniture supplier), and Harford Forest (furniture installation). Several of these companies already had long-term relationships with T. Rowe Price.

Through October 2018, five of the nine projects under this contract had been delivered, and the remaining four should be completed by November 2019.

One of the things that makes IPD contracts different from other construction delivery pacts, explains Dean, is that “they’re written like a manual. They describe how and when each party works together, and each step of the process, all the way through post occupancy.” He notes that the contract has a “team structure” that organizes partners into senior management, project management, and implementation groups.

No change orders, nor lawsuits against partners, are permitted under T. Rowe Price’s contract.

“It’s amazing how people are willing to work together when you remove that risk,” says Nugent. If savings are identified before the target cost is set, participants retrieve 20%; if found after, they get 10% of the savings.

There are two incentive compensation layers in the contract: at the end of the design, and at the end of the construction. Dan Jones, Senior Associate and Project Director in Gensler's Baltimore office, says there are four key periods during the contract when participants can “draw” on their share of any savings.

“The benefit for us is that we can invest the savings back into the project,” says Dean. On the Building 1 project, T. Rowe Price reinvested $446,000; on Building 2, $1.26 million; and on the three projects it started in 2017 (which consisted of renovating two floors and a café), $1.17 million.

The contract is set up to motivate participants to find ways to reduce a project’s costs. This inclusiveness appeals to Brad Boutilier, PE, Principal with TAI Engineering. He explains that, in a more conventional contract, the engineer is hired by the architect, who works for the developer. The architect may have already done preliminary work, like programming, without input from the engineering firm. And often, the engineer doesn’t have any contact with the project’s general contractor or construction manager until later in the game.

Under an IPD contract, “we’re in with the contractor from the beginning and have a better chance at finding cost savings in materials and installation processes. “It’s an all-hands-on-deck approach,” says Boutilier.

He was surprised, though, just how involved his fellow participants can get in a project’s details. On one of the early T. Rowe Price renovations, there was a snag in the delivery of mechanical equipment. Normally, the CM would be yelling at the vendor, but under the IPD contract, “everyone was calling, including Haworth,” says Boutilier. “How often does a furniture supplier get involved in those conversations?”

Teresa Terry, Haworth’s Global Accounts Manager, notes that participants signed to IPD contracts sometimes have to take one for the team. Installers recently told Haworth it could reduce double handling if it shipped in smaller trucks. (T. Rowe Price’s buildings can’t accommodate 53-foot trailers.) Normally, Haworth wouldn’t make that concession, but under the IPD contract it went back to T. Rowe Price to work out a solution.

“Chances are, this was going to cost us some money, so we had to decide if we’re going to take the hit to keep the client happy, or split the cost with T. Rowe Price,” says Terry.

Ray Crouch, Harford Forest’s President, notes that when projects get delayed, “we’re usually the one who gets crunched.” But under T. Rowe Price’s IPD contract, “we’re involved in design from day one. And the more efficient we can get the subs to be, the better. The unknown is significantly reduced.”

See also: Indoor-outdoor amenities open leasing value at a San Francisco skyscraper

Wrangling complexity

Turner’s Zettel has found that MEP contractors in particular are willing to enter into IPD “because they are frustrated by blueprints from architects and engineers that don’t make sense.” He cautions, though, that IDP contracts often misfire because “clients won’t invest in having a third-party coach in the room” to guide participants whose understanding about how these contracts function can vary widely.

“Everybody says they can do IPD and wants to collaborate, but the amount of transparency required isn’t for everyone,” says T. Rowe Price’s Dean. His company’s experiences have shown, though, that “the more complex the project, the more beneficial IPD is to the owner.”