U.S. metros take the lead in decarbonizing their built environments

By John Caulfield, Senior Editor

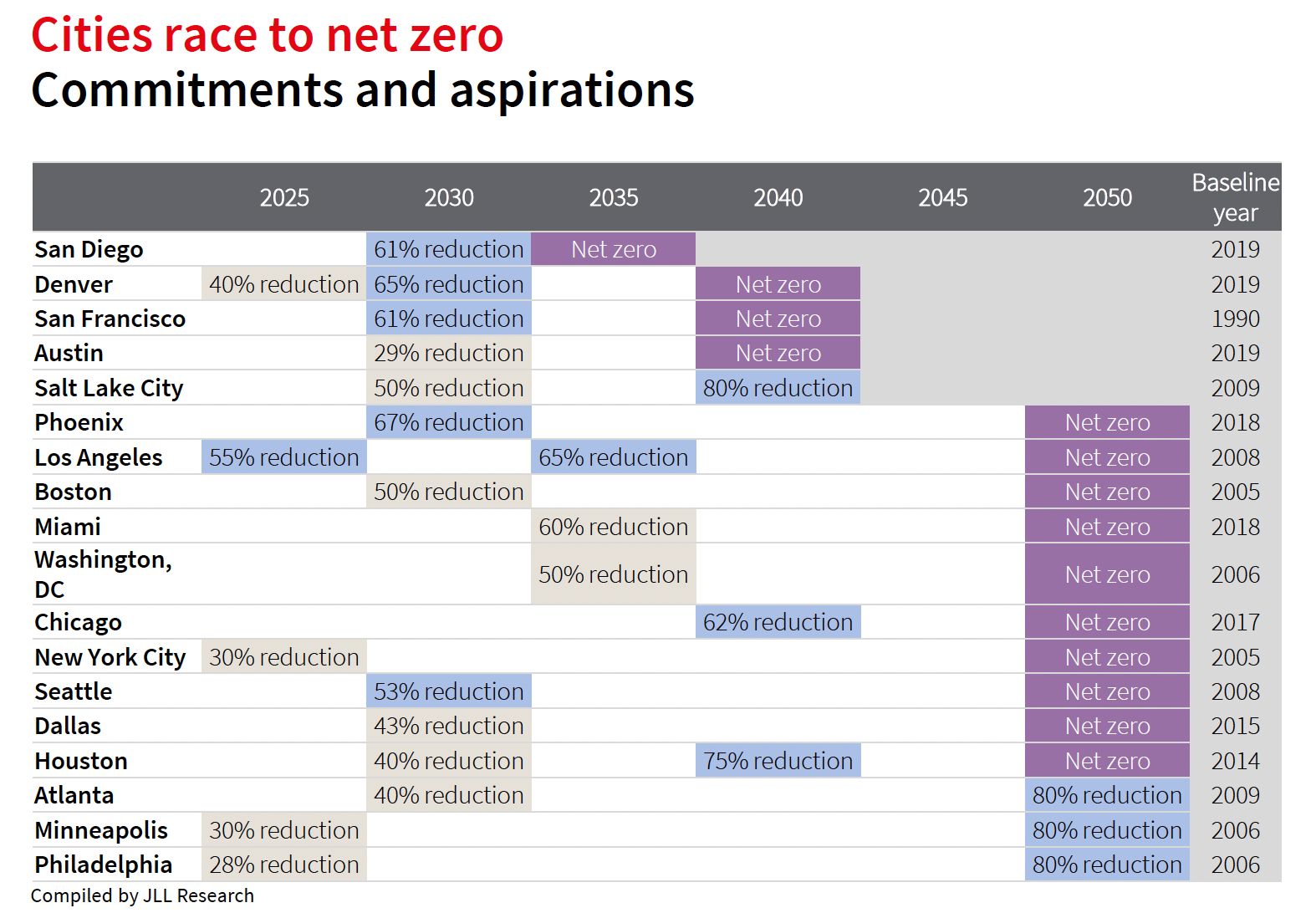

A growing number of local governments in the U.S. are setting bold net-zero carbon targets for how buildings are constructed, operated, generate power, and engage their communities and businesses. These metros are moving toward achieving their goals through a combination of incentives, public-private partnerships, and, when needed, “sticks” that can include heavy penalties for noncompliance.

In its report titled “Decarbonizing Cities and Real Estate,” JLL reviews the targets, regulations, reporting mechanisms, and other strategies and actions of 18 American cities, to help developers and investors navigate the evolving urban decarbonization landscape.

Decarbonization is at its moment of truth. More than 70 percent of total global CO2 emissions are generated by cities. At a time when U.S. cities in general still lag Europe in net-zero carbon targets and actions, the federal government, though the Inflation Reduction Act passed last August, made the single biggest climate-spending investment in the country’s history.

While U.S. cities lead on data disclosure—an important step on the decarbonization path—actual measures to reduce emissions are less prevalent. Still, a handful of progressive cities aims to reach net-zero target sooner than mid-century. For example, in a measure that was signed into law in August 2022, San Diego has committed to reaching net zero by 2035.

San Diego is among the “climate progressive” cities that JLL identifies, and include Boston, Denver, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco, and Seattle. “Climate aware” metros include Atlanta, Austin, Chicago, Minneapolis, Phoenix, and Salt Lake City.

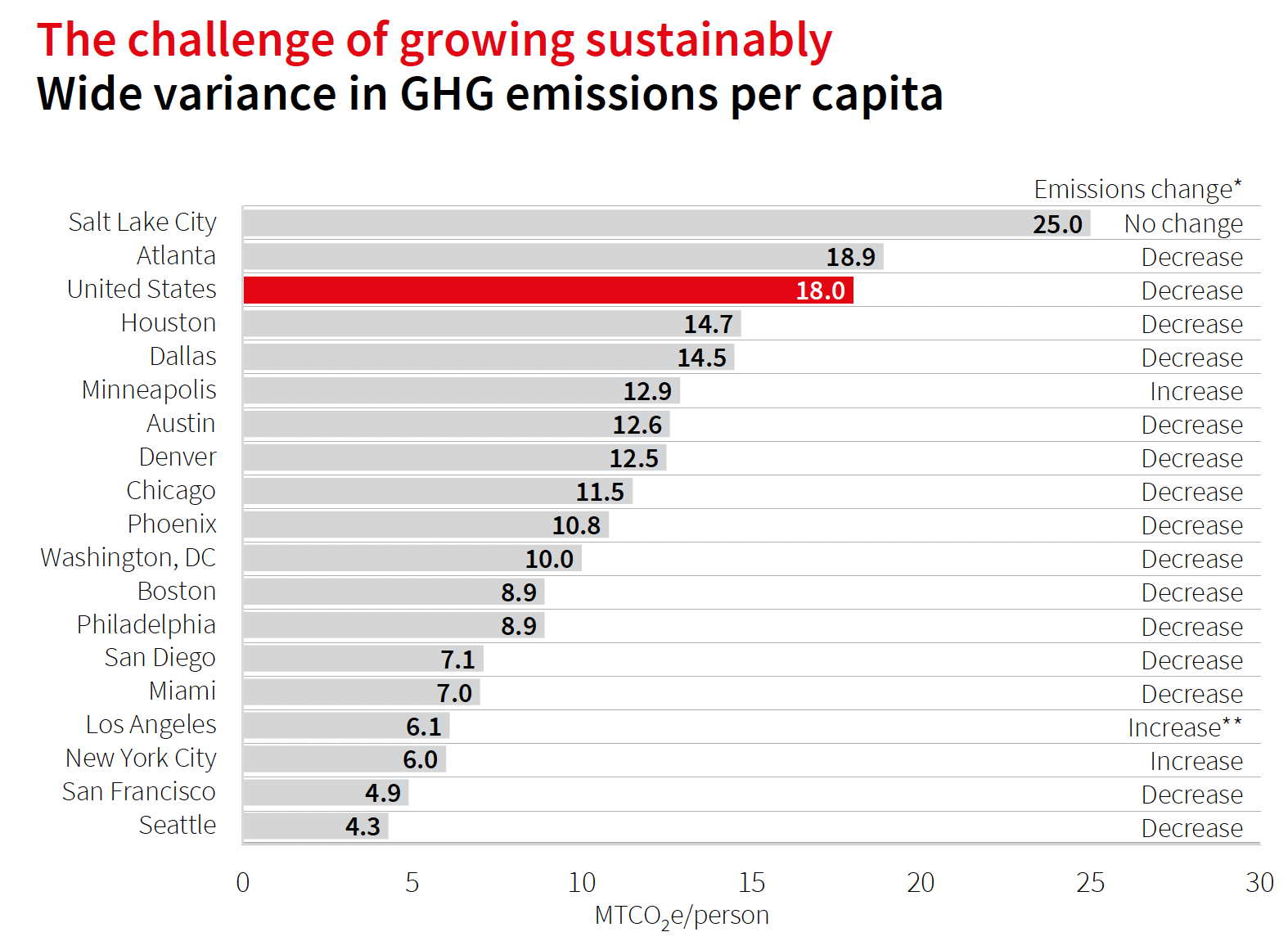

Salt Lake and Atlanta are the only two of the 18 cities JLL tracked whose greenhouse gas emissions per capita are higher than the U.S. average of 18 metric tons (MTCO2e/person). Seattle’s is the lowest, at 4.3 metro tons.

JLL points out that many of the cities with higher per capita emissions are rapidly growing in population, and this increased in-migration is putting excess demand on the grid, as well as on transportation and construction. “Rapidly growing cities are facing the challenge of figuring out how to support growth while simultaneously trying to reduce emissions. But this also presents an opportunity for these cities to grow and build sustainably.”

Indeed, JLL notes that cities around the world have shown they can expand economically while reducing their carbon emissions. Washington D.C., for one, has cut its emissions by 40 percent over 2006 levels while increasing its GDP by 21 percent. But this a lot harder to achieve when GDP and emissions are decoupled, as in Texas, where emissions were up 1.5 percent over 2000 levels compared to a 79 percent GPD growth over the same period.

Rethinking new and existing buildings

When plotting a decarbonization strategy, some hard facts need to be considered about the future of the built environment:

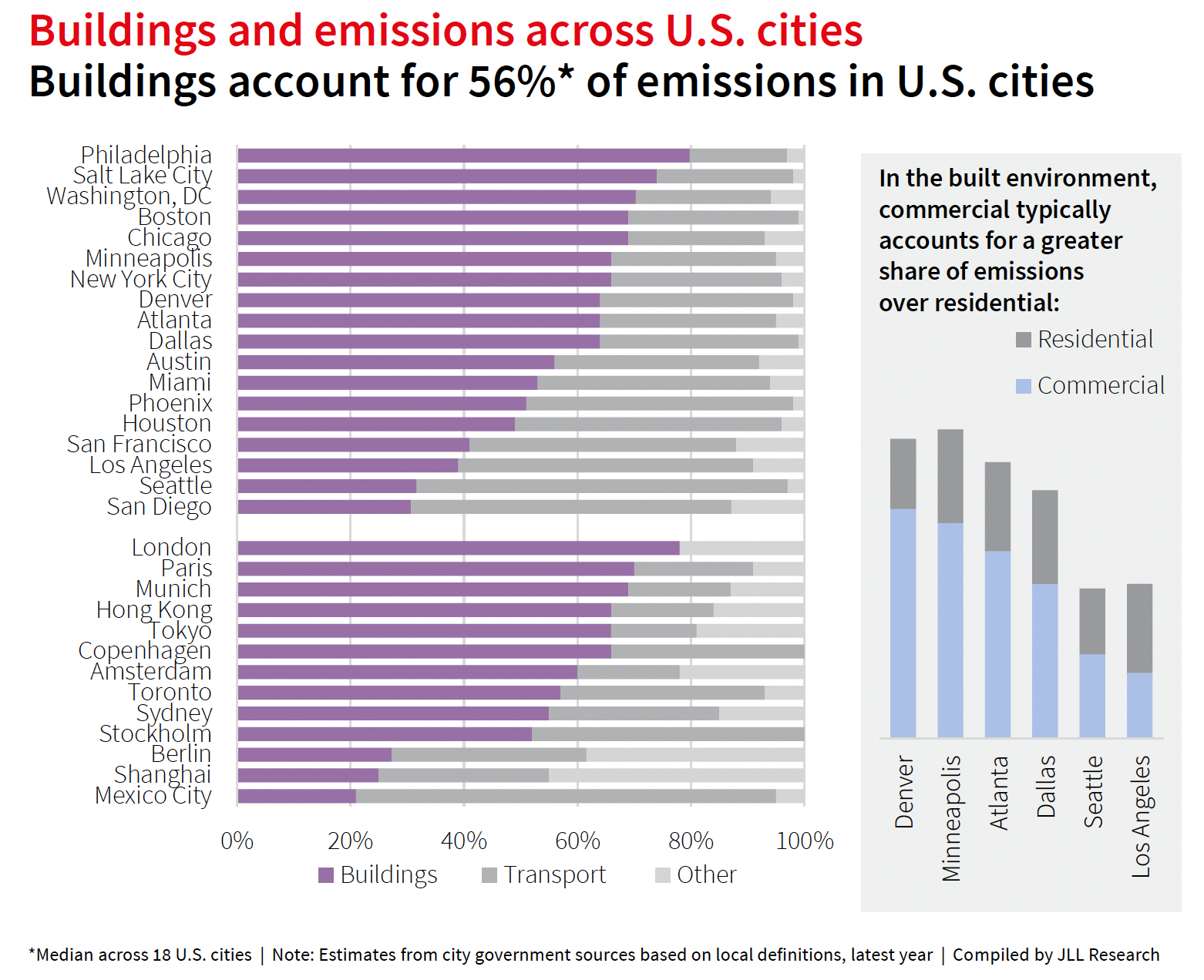

Buildings account for 56 percent of emissions in U.S. cities. Construction and demolition waste accounts for around 40 percent of solid waste in the U.S. Embodied carbon can represent as much as half of a building’s carbon footprint. And three-quarters of the existing office building stock that will be standing in 2050 has already been built.

By the end of this decade, 10 of the 18 cities that JLL surveyed will have some sort of net-zero or all-electric target for new construction. San Francisco is “leading the charge” and already has an all-electric new construction ordinance in place that began in June 2021. It is also the only city to have a similar target for existing building stock that is earlier than their ultimate, overall emissions target, though it is limited to large commercial buildings.

Cities are also taking aim at existing buildings’ operations. New York’s Local Law 97 is arguably the most ambitious building emissions legislation enacted by any city in the world, states JLL. It places carbon caps on most buildings greater than 25,000 sf, impacting roughly 50,000 residential and commercial properties. These limits begin in 2024, with stricter limits going into effect in 2030. Failure to comply will result in a penalty of $268 per MTCO2e above a building’s respective limit.

Denver’s Climate Action Task Force was formed to help the city design building performance policy for existing buildings that prioritized health and equity, job creation and climate solutions. In 2020, the task force recommended targeting 17,000 existing commercial and multifamily buildings and bringing them to Net Zero Energy by 2040 through policy that includes energy-efficiency and electrification requirements beginning in 2025. The group also recommended a sales tax, which would generate up to $40 million in funding each year and would go toward reaching the city’s climate goals equitably. The sales tax has been approved by voters.

Cities are also incorporating a building’s life cycle into the decarbonization planning. Consequently, retrofitting is “the responsible course of action when considering the embodied carbon implications of new construction,” says JLL’s authors of the report. JLL reckons that retrofitting rates will need to exceed 3 percent to meet 2050 CO2 emission reduction targets (the rate is currently 1-2 percent).

JLL singles out Austin for its “impressive goal” to reduce 40 percent of its embodied carbon footprint of building materials used in local construction by 2030.

Some cities seek energy independence

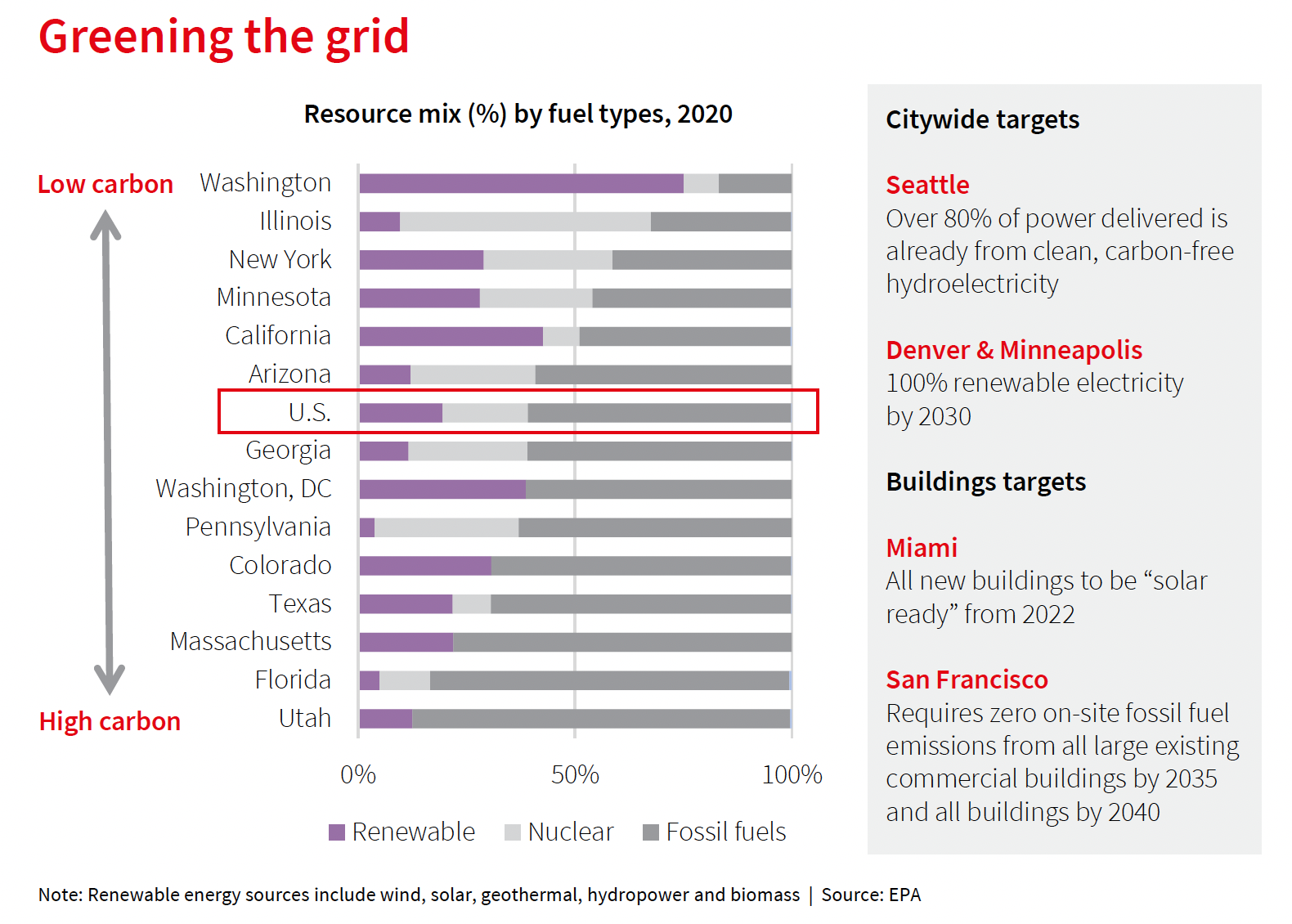

JLL’s report observes that on the national level, decarbonization has focused on how to shift the power sector to cleaner energy sources. Locally, a growing number of cities are implementing intrusive policies aimed at electrifying their building stock so that they are ready to pull from clean energy sources, but the challenge is much greater for some markets.

“Locally, energy independence is an effective strategy for tackling both the transition to clean energy and mitigation of climate change across cities,” asserts JLL’s authors.

At a state level, Utah, Florida and Massachusetts still source around 80 percent of their energy from fossil fuels, inhibiting the clean energy targets of their main cities like Salt Lake City, Miami and Boston. On the other hand, some states, such as Washington, already use 80 percent clean energy, largely from hydroelectricity, and in 2005, Seattle’s City Light became the first electric utility in the country to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions.

Partnering for livability

The report concludes by advising developers and investors to think beyond carbon when strategizing. Partnerships “are crucial for success,” it states, because “they enable best-in-class practices and knowledge-sharing across different stakeholders.”

Decarbonized real estate brings value to all stakeholders. For cities, it helps create more livable and resilient cities and reach net zero targets. For corporate users, it helps with compliance, especially when considering incoming reporting standards, and allows for companies to exhibit their brand and credo in the spaces they operate in.

Essentially, businesses need to remain “in proactive mode.” By leaning into an ecosystem of partnerships, “all parties will be better able to bridge the gap between ‘intent’ and ‘action,’ and make the best of this vital decade of action.”