Intuitive wayfinding: An alternate approach to signage

“Signage is the wow moment of arrival – it’s how you know that you are there.”

This is a direct quote from a session on wayfinding at a NAI (National Association of Interpretation) Conference that I recently attended. At the time I thought what a sad statement. Not that I have anything against signage. It is, after all, a critical component of wayfinding. The thing I objected to is the all too common belief that signage is wayfinding. In fact, the best type of wayfinding is that which is intuitive.

Intuitive wayfinding is much like navigating via waypoints—moving from point to point to point. The skill in designing intuitive wayfinding is understanding the visual and physical clues that help pull people through a space without the need for intensive signage. In doing so, the interpretive journey is much less stressful and therefore, much more enjoyable.

The most ideal form of intuitive wayfinding is to have a visible destination. This could be the ultimate destination, or it could be a waypoint that helps guide one to their ultimate destination. This strategy requires that each destination is clear and that successive destinations are revealed as one moves along a path. A good example of this strategy can be seen at the Ford Orientation Center at George Washington’s Mount Vernon. As visitors enter the building, they are immediately drawn to a grouping of statues of the first family. As they arrive at the statues, the rest of the space is revealed with a direct view to other interpretive opportunities throughout the building, thereby intuitively moving visitors through the building and toward their ultimate destination—George Washington’s estate and mansion.

Upon entering the Ford Orientation Center, visitors gravitate to the life-size bronze statues of George & Martha Washington and their grandchildren. They are then naturally drawn to the lower lobby which features Mount Vernon in Miniature and a series of stained-glass panels depicting crucial moments in Washington’s life before entering one of two theaters to watch a 20-minute orientation film.

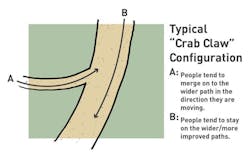

Understanding human nature is important to intuitive wayfinding as well. In the interpretive world, there is a commonly held belief that people’s intuition is to turn or move to the right. It’s a bit of a “chicken and egg” discussion as to whether our environments have conditioned us to turn right versus some subliminal tendency. However, I do think it is fair—at least in the United States—to assume people tend to move to the right, given equal choices. Other examples of human nature include the tendency to follow/stay on the widest, most improved path and the fact that people tend to be more aware of things at eye level—think of merchandising at your local supermarket. When designing spaces to be intuitively navigated, it is important to consider all of these and other aspects of human nature.

The “Crab Claw” configuration illustrates the natural human tendency to stay on or follow the widest, most improved path.

Skillfully incorporated, the use of views and light levels can also be utilized. Viewsheds are a particularly effective tool for moving people through buildings and orienting them to their surroundings. This strategy is currently being used in the new Pikes Peak Visitor Center, where the spectacular views are incorporated to help orient visitors arriving on different levels of the building. With regard to lighting, people are generally more comfortable in, and will choose well lighted areas. This is an important consideration, especially in interpretive spaces, where dramatic lighting is often utilized. Knowing these tendencies is important when trying to intuitively move people through space. For example, if one has a choice to go into a well lit room or one that is dimly lit, they will typically opt for the lighter space.

Wayfinding is a critical component of every interpretive journey. Certainly signage plays a role in informing and directing visitors through space. However, the most successful wayfinding is that which is intuitive, allowing for a more relaxed and therefore satisfying experience.

Alan Reed is GWWO’s President and Design Principal. He is a regular speaker on topics related to interpretive center design, including contextual design, and in 2011 he was elevated to the AIA College of Fellows specifically in recognition of his work on interpretive center facilities nationwide.