How beacons will change architecture

GPS has forever changed how we interact with our cities. If you get lost in a city today, you don’t look up at street signs, you look down at your phone. If you want to hail a cab, you signal your location by opening Uber rather than by waving your arms at the side of the road. If you want a restaurant recommendation, you ask Yelp for the best places nearby instead of asking your friends. We live in a world where GPS doesn’t just locate you on a map, it changes how you interact with the city around you.

Perhaps more crucially, GPS has begun to change the city. Real estate groups inside retail companies are mining spatial data from applications like Yelp to decide where to place their stores. Similarly, city planners are looking at this data to refine their city plans. Recently, the New York Times described how Uber is impacting LA’s nightlife because people are choosing to drive less often. Something as concrete and as dominant as LA’s car culture has been overturned by something as minor and as invisible as a GPS signal harnessed by a phone application. GPS is changing our cities.

The influence of GPS stops once you step inside a building. Typically it ceases working altogether, and when it does work, it lacks the fidelity to be useful in the context of a building.

There are many researchers and companies currently vying to create the equivalent of GPS for buildings (which we’ll refer to as indoor positioning in this article). People have been testing everything from optical sensors to magnetic and acoustic technologies. At the moment, there are many promises but little in the way of useful products.

In the past year, one technology has garnered a significant amount of attention: Bluetooth LE. Most of the hype has been fueled by Apple who introduced their Bluetooth based iBeacon standard for indoor positioning as part of iOS7 in 2013. Overnight, indoor positioning became available to millions of iPhone users. Last summer Apple upped the ante with the release of iOS8, which made significant improvements to their Core Location framework in an effort to create experiences that are more connected and more aware of the physical environment.

While Apple has been successful at promoting iBeacons, we’re not ready to anoint them the champion of indoor positioning. The iBeacon standard is still not widely adopted and other companies, notably Google and Samsung, are developing their own technology that is putting the squeeze on Apple to continue to innovate in this market. Regardless of who wins, as architects and designers, the release of beacon technology could (and should) mark a profound shift in the way we think about designing user experiences.

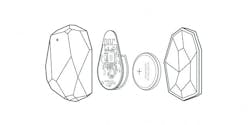

On the surface, beacons don’t sound like a technology that will revolutionize architecture. The beacons don’t really do much. They are these small Bluetooth devices that broadcast some identifying information at regular intervals. Basically, every second they send out a signal that says something like “I’m beacon 37”. Your phone and other devices can detect this signal and based on the signal strength they can approximate how far away you are from the beacon. Put enough beacons in a room and you can begin to triangulate your location. It is a simple idea that has profound consequences for how we use and design space.

When beacons were first introduced, the initial applications tended to focus on marketing. Companies could stick a beacon near a particular object in a store and when customers walked within range the customer’s phone would receive a notification (provided they had the store’s app installed). The notification could be anything from advertisements to coupons. While location-based ad networks appealed to retailers, many of these networks have already failed, primarily because no one wants to turn their phone into a location-aware billboard.

A better use for indoor positioning is in making applications contextually aware. If your phone knows where you are, it can become an interface to interact with your surroundings. In an art gallery, an application might show information about paintings as you walk up to them. In your home, an application like Beecon knows which room you are in and presents an interface to control the room’s lights. In your office, an application like Robin shows whether the meeting room you’re in has been reserved and allows you to book it (we have this application at CASE and it’s awesome!). These applications demonstrate that making the phone contextually aware also makes the phone a part of that context. The phone becomes an extension of the architecture.

Wayfinding is another obvious application of indoor positioning. If you are visually impaired, this has a huge potential to change the accessibility of unfamiliar spaces (see video above). Even for people with clear vision, indoor positioning offers a way to navigate otherwise confusing spaces. The SITA beacon registry for instance, will allow airlines to design phone apps that provide turn-by-turn directions to get from one gate to another. The research in this area will be further catalyzed by the FCC’s announcement in January that wireless carriers, like AT&T, will have to provide indoor location data with 911 calls within the next two years. As a result, it is estimated that there will be billions of dollars invested in indoor positioning over the next few years.

At CASE, we too are investing in indoor positioning. We believe that indoor positioning has the potential to transform the design and use of buildings, the same way we have seen GPS transform the design and use of cities. To that end, we have started an internal R&D program to explore the potential of indoor positioning technologies. This is the first of several blog posts that we will be writing over the coming months as we explore the potentials of indoor positioning technology. This video gives a little preview of what we've been working on, and also check out the work of Mani Williams, a PhD student at RMIT University who has been doing a research residency in our office for the past month.

About the Authors: Daniel Davis is a Senior Researcher at CASE. Andrew Payne is a Senior Building Information Specialist at CASE.