How one team solved a tricky daylighting problem with BIM/VDC tools, iterative design

Picture this: it is an uncommonly clear December morning in Corvallis, Ore., and a student is working hard on a white paper in the new Chemical, Biological, and Environmental Engineering Building at Oregon State University. His workspace is on the south side of the building and, therefore, the low winter sun is beaming onto his computer screen, making it difficult for him to work.

Fortunately for him, the project has integrated a series of interior full height sliding sunscreens at the adjacent window, which have operable louvers that allow him to eliminate this disruptive glare. Unfortunately for the building, while deploying and shutting the screen in order to block out the problematic exposure of the morning sun on the student’s work surface, the student has also eliminated the possibility for daylight to infiltrate the building and provided indirect illumination of the space. Even worse, the student then hastily heads to class and forgets to reopen the blinds, effectively forcing the electric lights to remain on in this area for the duration of the day.

It is this problematic scenario that the project team on the OSU Johnson Hall was able to resolve through a unique combination of traditional architectural design principles with iterative and empirical analysis. Utilizing dynamic parametric modeling and daylighting analysis software, we were able to test and tune our design response to this particular challenge with an agility and efficiency that has become increasingly vital in the world of compressed schedules and integrated project delivery.

"Utilizing dynamic parametric modeling and daylighting analysis software, we were able to test and tune our design response to this particular challenge with an agility and efficiency that has become increasingly vital in the world of compressed schedules and integrated project delivery." Scott Mooney, AIA, SRG Partnership

Before I describe this process, though, it is important to fully frame the issue that the team is trying to address around the context in which the project is being designed.

As previously described, the primary functional purpose of the interior sunscreens is to control the excessive contrast that can result from direct solar exposure of work surfaces after the autumn equinox. In previous projects, such as University of California Riverside School of Medicine and Research Building, SRG’s project team reconciled the need for daylighting with glare control by providing interior screens that are partial height. This serves to control visual contrast at the work surfaces, but maintain daylight autonomy through an independently controlled aperture above.

While this strategy has made sense in the past, the overlapping interplay of pure planar forms that can be found throughout the Johnson Hall interior suggested that the white birch sunscreens should extend the full height of the space that they occupy to maintain compatibility with the rest of the interior architecture. While this hinders the opportunity to have an independent "daylighting" portion of the window, it ultimately made sense in this instance in that it reduces the number of visible parts and pieces in the space, which have the potential to dilute the purity of the interior architectural forms that are unique to this project.

That being said, the true beauty in architecture lies at the intersection of aesthetics and performance. While the overall screen reaches the full height of the openings, the louvered areas within the frame have been designed to accommodate the varied needs of the users and the space as a whole.

In lieu of subdividing the window, the design team instead made the decision to zone the louvers in such a way that the lower portion of the louvered area will maintain operability, while the upper third will remain fixed. This would ensure continuous effective daylighting of the space from above, regardless of how the screen area below is being manipulated over the course of the day. While effective in theory, in practice there were a number of critical variables that needed to be clarified in order to ensure optimal performance.

For the winter months, when the screens were most likely to be fully deployed, we needed to learn the optimal fixed angle and spacing of the upper louvers to eliminate contrast and maintain daylight autonomy.

Grasshopper, Diva, and 3D Printing

Given the constraints that our team had established, both in terms of the architectural expression and the scope of the daylighting challenge, we chose to use dynamic parametric modeling in combination with daylighting analysis software to determine the optimal solution for this unique condition.

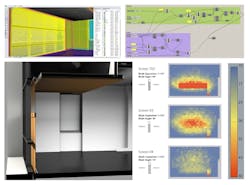

A first step in the process was for the team to build a parametric model of the screen using Grasshopper modeling software. Grasshopper allows the user to build a virtual model whose individual components can be quickly manipulated based on a certain set of established parameters—in this case louver depth, angle, and spacing.

The next step was to import different versions of this model into the Diva lighting analysis tool for Rhino. Using these tools in tandem through a rapid succession of designs options, it allowed the team a fast and effective way to fine tune and evaluate our screen design based upon both modeled performance and architectural expression.

As a follow up, we are also in the process of utilizing in-house 3D printing technology to create physical versions of these screens, as generated by the grasshopper model, in order to confirm our results in a more traditional daylighting model.

The end result is a design that deftly balances user control with tectonic clarity and energy efficiency. Each decision was made with a clear understanding of the ultimate intent, with equal weight given to performance, experiential, and aesthetic concerns. In its own small way, this example contributes to the greater architectural legacy of SRG that harmonizes research-based conclusions with rigorous and elegant architectural solutions that are uniquely shaped by climate, context, and composition.

About the Author: Scott Mooney, AIA, has been in the architectural industry since 2005. He received a BA in Urban Studies from Stanford University in 2001 and an MArch from University of Oregon in 2005. His primary interest is in Integrated Design, with a focus on finding synergies that support beautiful and holistic solutions for any architectural or design challenge. With a dual focus on ecological sustainability and design excellence, Mooney is passionate about public interest design and being a part of projects that serve the community at large. More on Mooney.

About the Author

SRG Partnership

SRG provides architectural services rooted in idea-driven design that respond to each project’s mission, program and context. BLG features articles on sustainability, research, culture and architectural practices written by SRG’s staff, showcasing each individual’s voice speaking passionately about a subject. These stories celebrate why we choose to devote our professional lives to design. Visit our Ideas page for more blog posts from our experts. Follow us on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter.