Building façade innovation: Water won’t dissolve this sugar cube

Who says the façade for a renovation and restoration project needs to be stodgy? Certainly not New York-based architecture firm ODA, which recently finished its conversion of the former Arbuckle Sugar Refinery on New York City’s East River into 10 Jay Street, a Brooklyn waterfront jewel box with 10 stories of open floor plates.

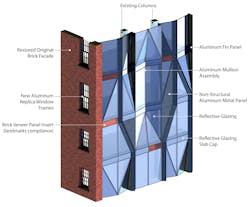

The 230,000-sf building combines three of the building’s original brick façades with a new unitized glass-and-steel waterfront curtain wall. (The original waterfront façade was torn off the building in the early half of the 20th century.)

The new curtain wall’s design was inspired by the form of a sugar crystal, meant to harken back to the building’s original use as a sugar refinery, while also adding a contemporary touch to the landmarked building. Additionally, through the use of parametric modeling, the façade will produce dynamic fragments of reflections of the river, the park, and the surrounding city.

The 10 Jay project had to manage a delicate balancing act to maintain the relationship between the neighborhood and the waterfront, as well as heritage and innovation. Photo: Pavel Bendov

“The intent was to restore the parts of the building that are historical and add a contemporary architectural element,” says Christian Bailey, AIA, LEED AP, Founding Principal, ODA.

Before 10 Jay Street’s new sugar-crystal-inspired design could be put into motion, it needed to be approved by the Landmarks Commission Board, which typically does not approve such modern interpretations in DUMBO and can hold jewel-box designs to intense scrutiny. Ultimately, the façade and interior earned 15 permits from New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission, with one permit noting the new look “aligns in keeping with the utilitarian character of the building.”

A new way of doing things: unitized curtain wall

ODA took advantage of the technical advances the AEC industry has developed in recent years with regards to unitizing the wall. In the past, the primary way to assemble curtain walls was through “stick building.” With this type of construction, the curtain wall frame is constructed primarily on site, piece by piece.

On the 10 Jay project, ODA decided to forgo the traditional stick building technique and instead opted for a unitized construction approach. The firm, after a global search for a manufacturer that could produce what was needed within budget, selected KPA Studio to construct the curtain wall.

‘10 Jay Street honors the relationship between neighborhood and waterfront, heritage and innovation.’ — Christian Bailey, AIA, LEED AP, ODA

Engineering and fabrication assembly took place in a factory in a controlled environment. The curtain wall units were then transferred to the site, which enabled “superior quality and facilitated ease of installation once on site,” says Bailey.

The unitized construction approach and the fact that the waterfront façade was installed simultaneously while the landmark restorative work was done on the other three façades helped the project stay on schedule and within budget.

In order for the new glass-and-steel façade to connect to the existing brick façades (and for restorative work to continue during installation), tolerances needed to be built in. “Items such as building and thermal movement and seismic anchoring requirements needed to be incorporated within the tolerance set in the design,” says Bailey. “Once this has been engineered, then you can start to incorporate the marriage of the two wall types as it pertains to weatherability and waterproofing.”

Weatherability and waterproofing are an important consideration when designing and installing an exterior assembly. The 10 Jay Street façade included a couple curveballs the team needed to consider: the myriad angles required to achieve the sugar crystal design, the fact that the new façade would connect to a restored brick exterior, and the building’s location right on the riverfront in New York’s flood zone.

The building’s location on the East River means the façade will be subjected to high winds and moisture, making the connection points between the restored brick walls and the new glass exterior critical. Source: ODA

“Resiliency was at the forefront of our thought process when designing the building,” says Bailey. The waterfront façade was specially engineered to resist the high winds and moisture coming off the river, and because a unitized approach was taken, stringent quality was maintained as the curtain wall was assembled in the factory before being transferred to site. This meant, despite the multifaceted design and the combination of new construction and renovation, the façades came together and formed a waterproof seal without issue.

ODA hopes the resulting building, a successful marriage between old and new, will act as an example of how cities around the world can recover and readapt buildings without completely obfuscating a given building or neighborhood’s heritage.

“10 Jay Street honors the relationship between neighborhood and waterfront, heritage and innovation,” adds Bailey. “A delicate balance of glass, steel, brick, and spandrels gives the building gravitas without compromising industrial heritage.”