Steely resolve: Carnegie Mellon University fuels Pittsburgh's post-industrial reinvention

This year, the Regional Industrial Development Corporation of Southwestern Pennsylvania (RIDC) turned over the keys for two floors of the first building at Mill 19 to Carnegie Mellon University, which is subleasing 94,000 sf for its Manufacturing Futures Initiative (MFI) and the Advanced Robotics Manufacturing Institute, of which CMU is a member.

Catalyst Connections, which provides training to small manufacturers, is leasing the third floor of Building 1. By the end of this year, Building 2 at Mill 19 should be ready for occupancy, and it has been reported that Aptiv, a global supplier for smart-vehicle parts, will lease 70,000 sf there. Tenants for Building 3 have yet to be disclosed, but RIDC President Don Smith has stated that one of Mill 19’s buildings would be leased to a company focused on artificial intelligence.

The redevelopment of Mill 19—a 1,500-foot-long, 180,000-sf former LTV Steel rolling plant built in 1943 and closed in 1998—to accommodate 264,000 sf of new rentable space nestled within the original steel structural shell, is the latest manifestation of the city of Pittsburgh’s post-industrial renaissance. That revival is most definitely an “Eds and Meds” story, attributable in large measure to businesses flocking to Pittsburgh to be closer to the talent and research generated by locally based Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh, as well as an expanding UPMC healthcare system.

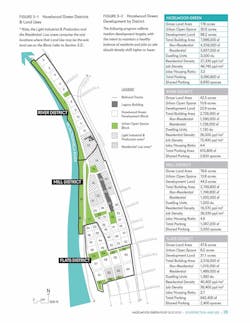

Mill 19 sits on 12.6 acres that RIDC owns. The parcel is part of the 178-acre Hazelwood Green, a former steel mill site along the Monongahela River, whose brownfield redevelopment plan over the next two decades calls for nearly 31 acres of open public space, 3,500 housing units, and about 4.4 million sf of nonresidential buildings for offices, hospitality, retail and restaurants, education, and R&D facilities.

Smith says there’s no timetable for when Hazelwood Green’s vertical construction might begin. Rebecca Flora, AICP, LEED AP, President and CEO of ReMake Group, who is serving as Hazelwood Green’s project manager, has been working with Mascaro Construction and GBBN Architects to “stabilize” two buildings on that site: the 22,619-sf Roundhouse building, which dates back to 1887; and the 3,405-sf Pump House, circa 1870.

(CMU has been involved in the design of this site’s first public space, a two-acre plaza. And RIDC and CMU have been coordinating with Oxford Development on site infrastructure and parking as CMU moved toward occupancy at Mill 19.)

Three foundations—Heinz Endowments, Richard King Mellon Foundation, and Benedum Foundation—have owned 165.6 acres of this site since 2002. “It’s a unique property in that it was purchased by private foundations for public use,” observes Tim McNulty, a spokesman for Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Perduto.

But it wasn’t until Carnegie Mellon agreed to lease space at Mill 19 that Hazelwood Green’s redevelopment—whose plans once considered including a casino—came into clearer focus.

“There’s no question that we can take credit for getting this started,” says Gary K. Fedder, MFI’s Director and the Howard M. Wilkoff Professor of ECE and Robotics at Carnegie Mellon.

Indeed, Hazelwood Green’s proximity to Carnegie Mellon’s students and faculty is a “big factor” in creating interest in this redevelopment among prospective tenants, says Flora. That access, she’s convinced, “should play out for a long time.”

Decades-long commitment

After the steel industry started collapsing in the late 1970s, Pittsburgh has been reinventing itself as a science, medical, and academic hub. Pittsburgh is now viewed as a global center for R&D in robotics, AI, autonomous vehicles, and biotech, says Smith. And those recognitions stem from the growth and reputations of its universities and medical centers, “whose impact continues to this day,” says McNulty.

“The university and hospital communities can put stakes in the ground, and people will come,” says Bob Reppe, CMU’s Senior Director of Planning & Design, whom BD+C interviewed with Ralph Horgan, the university’s Associate Vice President, Campus Design and Facility Development.

Indeed, CMU’s role in Pittsburgh’s recovery can be traced back to 1983, when a collaboration among CMU, RIDC, Pitt, the Urban Redevelopment Authority, and several other regional and state partners reclaimed a 48-acre former steel mill site in the South Oakland neighborhood for an office park called Pittsburgh Technology Center. That park now has nine buildings. A 100-key, $14.7 million Indigo Hotel opened there in 2018, and a six-story office building is scheduled to open this year.

Fedder notes that while Pittsburgh’s economy took a serious hit when its steel industry imploded, it was also among the U.S. cities with the greatest potential for rebirth. Vivian Loftness, FAIA, LEED AP, a CMU professor and the former head of its School of Architecture, points out that there are 27 “completely unique Main Street neighborhoods” in Pittsburgh that have avoided the wrecking ball that was common of other metros’ urban renewal.

CMU has been one of the key players at the heart of Pittsburgh’s redevelopment. Take, for example, 2nd Avenue, a main road for Hazelwood Green along the riverfront. That’s where, in 1999, the university opened its Entertainment Technology Center, which churns out graduates for the gaming industry.

A more telling example of how a university can kickstart a neighborhood’s recovery is found in Lawrenceville, a once sketchy community that 25 years ago was little more than abandoned row houses and factories. In 1995, CMU leased 82,132 sf in a reconstructed foundry building that dated back to 1898 for its National Robotics Engineering Center (NREC). Now, Lawrenceville is thriving. Its adjacent Strip district has come to be known as “Robotics Row.” NREC is surrounded by other resurrected buildings leasing space to CMU’s corporate partners, says Mark Nolan, the university’s Associate Vice President–Institutional Partnerships. These include the recently opened Tech Mill 41 at The Foundry, a 73,500-sf office building inside a former machine shop.

The economic impact of NREC has bolstered the neighborhood’s real estate values, too: Smith notes that 10 years ago, RIDC paid $27,000 to purchase a house in Lawrenceville. Now, an entry-level townhouse starts at $350,000.

Lawrenceville’s resurgence didn’t happen overnight. “NREC was 15 years ahead of its time, and it was only in the last five years that redevelopment started to spring up around it,” says Reppe. Still, he and Horgan are convinced that lightning could strike again at Hazelwood Green. NREC—with its modular design that can easily adjust to different tenants—is the template for Mill 19’s redevelopment and leasing strategies.

“We were grateful that Herman Herman [NREC’s Director] was able to engage early on for the design team to understand how NREC’s high bay, project cells, and supporting spaces are laid out to maximize efficiency,” recalls Nicole Graycar, AIA, Senior Project Manager and Architect with CMU, who is managing the Mill 19 reconstruction.

She elaborates that the Mill 19 project needed “a very fluid design approach, as program requirements, core and shell issues, and site impacts have changed, sometimes on a day-to-day basis.” The project will deliver “an extremely flexible ecosystem of spaces,” while at the same time honor the mill’s manufacturing past. “Our palette is very constricted: concrete, steel, black mullions, with cold-rolled raw steel panels and clear-coated white oak,” says Graycar.

Leaders from CMU and the city signed a sculpture commemorating Mill 19’s groundbreaking, which will sit in the first building’s lobby. (CMU worked with Renaissance 3 Architects and Jendoco Construction on the fit out. Minnesota-based MRS and Turner Construction were the architect and GC, respectively, on the Mill 19 reconstruction.)

Setting the stage for startups

CMU’s impact on Pittsburgh’s economy extends beyond urban redevelopment. NREC, for example, has spun off several companies, says Fedder, including Carnegie Robotics (whose principals helped start Uber and Argo), Titan Robotics (which focuses on scraping the surfaces of aircraft), and Platypus (which uses autonomous vehicles for water analytics). Another NREC alum started Aurora Innovation (autonomous vehicles), which in January raised $530 million in venture capital. There have been about 35 startups connected with robotics alone, and several others in manufacturing and technology, including Duolingo, a free language learning platform.

Since its inception in 2008, CMU’s Center for Technology Transfer and Enterprise Creation has incubated 288 companies: 176 have been indirect startups by faculty, students, and staff; and 112 direct startups that licensed CMU-owned intellectual property. Since 2011, CMU-incubated startups have raised more than $1 billion in venture capital financing.

“There’s an amazing array of educational leadership” in Pittsburgh that entrepreneurs and companies want to tap into, says Loftness. And these relationships are symbiotic because “when we have a vibrant Pittsburgh, that helps the university to compete for students and faculty with Boston and San Francisco,” says Fedder.

Smith notes that several CMU startups have been acquired by global players. The city is working harder to get other startups to a point of critical mass in order to optimize their economic importance. “We want to be the center of gravity for robotics and AI,” says Smith.

CMU has 350 corporate partnerships that revolve around hiring its students, using its labs, and accessing its research. About 200 of these partnerships are active in research projects with the university. “And wherever I go, the question, ‘Is there space available in Pittsburgh?’ always comes up,” says Nolan, who adds that the best way for companies to take advantage of CMU’s resources is to operate in the city.

a reason to relocate

Hazelwood Green, which was rezoned recently for greater density and sustainability, is being positioned to potential tenants as an extension of CMU’s campus. McNulty and Smith confirm that there will be some form of transportation between the site and campus. (Gondolas have even been suggested.)

The university continues to expand and build on its seven million-sf Oakland campus. Horgan points specifically to several new construction projects: the 315,000-sf Tepper Quad, the Wilton E. Scott Institute for Energy Innovation, and the 62,000-sf Cohon University Center addition.

'The university and hospital communities can put stakes in the ground, and people will come.' — Bob Reppe, Carnegie Mellon University

CMU’s fingerprints can also be detected on another of the city’s reclamation projects, Bakery Square within the once downtrodden East Liberty neighborhood.

In 2005, CMU opened on its Oakland campus its $27.9 million, 136,000-sf Collaborative Innovation Center, whose purpose is to provide office and lab space for tech companies that wanted to work with the university. “They want to have the type of interaction you can only have when you’re in close proximity,” said Smith at the 2003 groundbreaking. “They want to be close to the students.”

One of CIC’s first tenants was Google, which leased 20,000 sf. But by 2009, Google had outgrown that space, and moved its offices to 44,000 sf inside a former Nabisco factory at Bakery Square that dated back to 1918 and had closed in 1998.

“This was a breakthrough moment,” recalls Reppe about that relocation. “The flare went off,” letting businesses know that there was an infrastructure ecosystem for those that wanted to open shop in Pittsburgh.

Reppe isn’t exaggerating. Google now leases about 300,000 sf on six floors in two office buildings at the mixed-use Bakery Square, whose developer, Walnut Capital Partners, is currently completing a $30 million, nine-story, 300,000-sf Building Office Three there. (CMU provides shuttle services between its campus and Bakery Square.)