The American Institute of Architects (AIA) Committee on the Environment (COTE) this week named the 2019 recipients for its highest honor, the COTE Top Ten Awards.

COTE bestows the award annually on 10 design projects that have expertly integrated design excellence with cutting-edge performance in several key areas.

In order to be eligible, project submissions are required to demonstrate alignment with COTE’s rigorous criteria for 10 measures that include social, economic, and ecological values. The five-member jury evaluates each project submission based on a cross-section of the 10 metrics balanced with the holistic approach to the design.

On the 2019 COTE Top Ten jury: Nancy Clanton, PE, LEED Fellow, CEO, Clanton & Associates; Paul Mankins, FAIA, LEED AP, Principal, Substance Architecture; Christiana Moss, AIA, NCARB, Principal, Studio Ma; Christoph Reinhart, Professor, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; and Allison Williams, FAIA, Principal, AGWms_studio.

The 2019 COTE Top Ten winners are (text and images courtesy AIA and project teams):

Amherst College Science Center, Amherst, MA | Payette

The Amherst College New Science Center provides state-of-the-art facilities and a flexible space to support the college’s science programs and students through the next century while reducing energy usage by 76 percent compared with a typical research building. The New Science Center is sited at the east edge of the new Greenway landscape, connecting the sciences to the rest of the Massachusetts campus. The building is organized around “the Commons,” a dramatic multistory atrium. The Commons creates a community of science through the five forms that make up the building: two four-story energy-intensive laboratory wings tucked into the east edge of the sloping site and three two- to three-story pavilions of low-intensity programming set in the landscape to the west, facing campus. A roof that floats above the Commons unifies the building while also providing a quiet visual datum for the undulating Pelham Hills beyond.

An array of skylight monitors animate the roof, further signifying the building’s scientific purpose and its commitment to sustainable performance. The Commons’ roof monitors integrate architectural and mechanical elements that provide an overall comfort conditioning solution: chilled beams, radiant slabs, acoustic baffles, and a photovoltaic array. A central gap between the laboratory wings at one end of the Commons offers views to the east, drawing nature into the building. It also serves as a circulation nexus with an interior stormwater feature, fostering strong biophilic connections. The Greenway’s new surrounding landscape, when met with the transparent, west-facing glass façade, provides the Commons with remarkable views of native ecology, blurring the edges of the central living room and the outdoors. In turn, the gathering space feel like an extension of the outdoors.

The Frick Environmental Center is a living learning center for experiential environmental education. The building and its four-acre site act as a gateway to Pittsburgh’s wooded 644-acre Frick Park and embody the neighborhood-to-nature ideal that served as inspiration for the park’s formation more than 90 years ago. The center exemplifies principles of equity, experiential learning, and public engagement and is welcoming and inclusive for all. A joint venture between the city of Pittsburgh and the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, the center is LEED Platinum and Living Building certified, municipally owned, and has free admission. The center demonstrates the conservancy’s mission to restore the city’s deteriorating parks and reestablish a cycle of stewardship. Intensive community outreach and engagement took place during all phases of planning, design, and construction and continues well into operation to maintain the pride of ownership that builds long-term sustainability.

As the main classroom for Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy’s educational programming, the building and surrounding site are educational ecosystems for both immersive outdoor education and hands-on lessons in sustainability. Biophilic design strategies used throughout the project both beckon and shelter, gently nudging park visitors from the adjacent neighborhoods toward the heart of the wooded park beyond. The three-story building is nestled into an existing slope and sheltered by a simple roof resting on slender columns. A service barn, outdoor amphitheater, and restored historic stone gatehouses and fountain complete the site. The center’s beauty and sustainable story inspire new visitors while simultaneously encouraging them to grapple with the impact of our humanity in a dynamic natural ecosystem—one that we are part of, yet inherently distanced from. The center provides the stage for public discourse about this delicate balance.

This is the story of a community imagining a different future for itself, beginning with seeking peace in the region through access to clean water and then enhancing educational opportunities for the primary school graduates. Because of its remote location in northwest Kenya and within a community of subsistence farmers and pastoralists, true sustainability has been the driver for each design decision, including design integration of a severe environment, an engaged community, and local economics. The project is a high school campus that will educate 320 students upon full buildout. Structures accommodate classrooms, offices, dormitories, and teacher housing at its core. The local conditions are harsh by any standard: drastic seasonal swings between dry seasons with harsh equatorial sun and wet seasons with pronounced rainstorms that erode the dry, sparsely planted land with no connection to a municipal water or power system. Design constraints and opportunities are dictated by the place: zero net energy, zero net water, emphasis on regional materials and local labor, and community engagement to ensure generational success.

The renovation and expansion of One Spadina Crescent for the University of Toronto’s John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design (DFALD) embodies a holistic approach to sustainable design. The project focused on the context of the city and dynamic use patterns over time as opposed to focusing exclusively on static accreditation frameworks. The project strove to distinguish itself in utilization efficiency, energy/water/material efficiency, properly insulated building fabric, indoor environmental quality, landscape, and urbanity. Most important, the project anticipated the dynamic nature of design education and technology through its flexibility and resilience.

The project objectives were twofold: (1) rehabilitate the landscape, historic Knox College architecture, and urban significance of Spadina Crescent (2) demonstrate DFALD’s objective of overt sustainability through the deployment of materials and systems to accommodate a program for studio space, workshops, classrooms, offices, a library, a cafe, a gallery, an auditorium, a Living Lab, a Fab Lab, a public amphitheater, and an event terrace. Design strategies were multifaceted to address environmental, economic, and social values. One example of this is the new, dynamic ceiling on the third floor of the new addition. Using the cantilevered structural logic of the Firth of Forth Bridge, the ceiling of the studio is shaped to integrate daylighting, hydrological control, and structural optimization, creating a desirable space that engages the senses while simultaneously saving energy and water and serving as a pedagogical tool. For years, many initiatives have attempted to preserve, reuse, and repurpose One Spadina Crescent. This project has revived the site and offers a north face for the first time in its history. The preservation of the north addition will have value in how it establishes a dialogue with the urban and campus context and serves as a critical piece of infrastructure for the city of Toronto.

Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Complex, Northeastern University, Boston | Payette

Flow and movement define the form language of the Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Complex (ISEC), expanding Northeastern University’s Boston campus to the south of a major rail corridor and reconnecting the diverse neighborhoods of Fenway and Roxbury. Dynamic movement systems permeate the project, like pebbles in a stream defining the landscape paths through bioswales and the dynamic solar veil shading the office. The building form is intrinsically linked with high-performance architecture through parametric design and energy modeling to achieve an integrated design. The building leverages passive elements to reduce energy demand and employs high-tech energy recovery systems to further reduce energy use. This cutting-edge facility represents a major expansion of research at Northeastern University and provides a 236,240 gross sq ft home for four interdisciplinary academic research disciplines: engineering, health sciences, basic sciences, and computer science.

The project elevates Northeastern University’s capability to compete as a premier research institution. Aggressive targets and an integrated approach to sustainability was ingrained from the planning stages throughout the design process, impacting everything from the programmatic organization of the building to the design of the building enclosure. The layered organization of the research lab not only creates a vibrant interior culture within the building but also minimizes energy usage while zoning areas for future flexibility. A daylight-filled atrium forms a new campus-scale public space surrounded by intimate collaboration spaces. In addition, it simultaneously acts as a mixing chamber for a cascade air system to recycle air throughout the building. Constructed on an urban brownfield site consisting of an existing surface parking lot set between two garages, the ISEC represents the completion of the first phase of the newly planned 660,000 sf academic precinct.

Lakeside Senior Apartments, Oakland, California | David Baker Architects

The building provides 92 permanently affordable homes for low-income and special-needs, formerly homeless seniors, many of whom had been displaced by rising Bay Area housing costs. This site previously served as the underused parking lot for adjacent senior housing. The new building accommodates lost parking and adds capacity in a below-grade garage topped by five levels of housing and community spaces. The design underwent early variations as the developer acquired and incorporated small, irregular adjacent sites. The final assembled site offered additional capacity and a regular shape, which streamlined design.

The goals were to add comprehensive affordable housing and supportive services, activate sidewalks to increase safety and enjoyment, and create a sense of place. This building brings focus to an area with an existing senior community, good transit, and vital neighborhood resources. A central courtyard lined with a transparent glass fence provides a protected space with a visual connection to the larger neighborhood. The top-floor community suite—garden, event kitchen, and wellness room— provides sweeping lake views for all residents. Care was taken to step the building massing down toward the lake, emphasizing the proximity to this wonderful urban resource and protecting neighbors’ light and views. The developer had a LEED goal from the outset. Shared by the design team, this goal informed all decisions about materials and systems, inspiring a range of complementary strategies that resulted in Platinum status. The building design begins with a tight envelope and massing articulation that responds to orientation. Strategies focus on reducing energy and water demand first, followed by efficient, cost-effective equipment that needs minimal maintenance and takes advantage of heat recovery and solar energy to reduce loads and offer multiplying benefits. For example, heat recovery ventilators in units provide balanced ventilation, improve comfort, and increase building durability while limiting cost burdens for low-income residents.

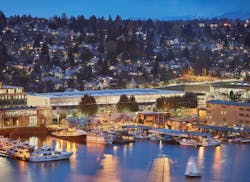

Seattle is the nation’s fastest-growing big city, with 18.7 percent growth over the last 10 years. It’s also one of the nation’s densest cities, with more than 8,600 people per square mile. With more people comes more waste, recyclables, and compostables—taxing the city’s aging infrastructure. To reach its zero-waste goal, Seattle needed a more efficient transfer station than the 1960s-era facility that stood on the site. On a typical day, the new station receives approximately 400 tons of various materials and is designed to handle up to 750 tons per day to accommodate anticipated growth. Integrating this large-scale infrastructure into a dense, low-rise neighborhood was the biggest challenge.

Bermed into a sloping 5½-acre site between Lake Union’s recreational waterfront to the south, single-family residences to the northeast, and mixed uses to the west, the facility consists of two low-slung buildings on either side of a weigh-scale yard. The main structure comprises a 63,246-square-foot tipping and transfer floor, an administrative block, and a lower level for compacting and collection. The 10,000-square-foot recycling building allows self-haulers to divert materials from the waste stream, a function the older facility lacked. The challenge facing the design team was to replace the out-of-date facility with one that was larger and more efficient while meeting the demands of two abutting residential communities. The massing responds to the most stringent constraint: a building height limit of 78 feet above sea level—equal to the existing grade at the site’s top corner, enabling the hillside neighborhood to overlook the facility to take in lake and city views. Rooftops are clear of mechanical equipment, supporting photovoltaic arrays and greenery instead. In addition, the design incorporates queuing space inside the site to reduce congestion and noise impacts on the neighboring community. The mediation of industrial and human requirements is the station’s major achievement.

Oregon Zoo Education Center, Portland, Oregon | Opsis Architecture

Inspiring visitors to engage in sustainable actions is the mission of the design and exhibits at the Oregon Zoo’s Education Center. The center—the fifth project funded by the zoo bond—provides a home base for thousands of children who participate in camps and classes annually and serves as a regional hub, expanding the zoo's youth programs through collaborations with U.S. Fish and Wildlife and other partners. The center includes classrooms, meeting spaces, gardens, and a Nature Exploration Station (NESt), inspiring visitors to get outside, learn about nature, and take action on behalf of nature. Illustrating that “Small Things Matter,” the zoo provides its 1.7 million annual visitors with interactive exhibits that demonstrate how actions can help maintain a healthy planet. The center creates dialogue between the built and natural environment, with each interior space offering a corresponding visible and connected outdoor space.

The wood and steel woven structure of the NESt is inspired by the nests of animals creating shelter and order in the environment. The NESt is the center of activity that visitors access through large sliding doors. They learn the stories of local conservation heroes and access the turtle conservation lab and the Insect Zoo—where the smallest of animals can have the largest ecosystem impacts. Within a plaza at the west end of the zoo, the tight, irregular site has curving boundaries of exhibits, the zoo railway, a pedestrian path, and a steep south hillside. The building hugs the central plaza, and learning landscapes exist throughout. Inspired by the unique spiral patterns prevalent in natural systems, two curved roofs welcome visitors to the plaza. Sustainable elements, including solar panels, native plants, bird-safe windows, and rain gardens, are designed to educate the public. The center recently earned LEED Platinum certification with 82 points and Portland AIA’s 2030 COTE award.

St. Patrick's Cathedral, New York | Murphy Burnham & Buttrick Architects

Driven by social, ecological, and economic value, the 21st-century renovation of New York City’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral—the prominent 1870s religious landmark by James Renwick Jr., which was last renovated in 1949— achieved a 29 percent reduction in annual energy use and stabilized significant historic fabric while each year welcoming 5 million-plus visitors. Design solutions combined stringent conservation methods, 10 geothermal wells, fully integrated new mechanical systems, and strategic architectural interventions to enhance worship and functionality. Additions of modern glass doors and structural glass walls supported sustainability goals, creating an energy-saving enclosure, improving uses of the 1906 Lady Chapel, and enhancing visitor comfort while maintaining views of historic interiors, stained glass, and structures. The nine-year, $177 million effort impacts the entire city block-sized campus.

Preservation of failing marble, stone, plasterwork, and stained glass stabilized and improved original materials. New ancillary spaces create expanded social and worship opportunities, and 1960s-era mechanical equipment has been completely replaced. Long-concealed original elements were restored or re-created, with deference to Renwick’s neo-Gothic details and design intent. As reported in the New York Times, “trustees of the 138-year-old building, the centerpiece of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York,” wanted the church to maintain its historic fabric, even as major systems were upgraded and “it was going green.” Offering valuable post-occupancy lessons for making historic places effective, relevant and resilient, the wide-ranging conservation and retrofit improvements to St. Patrick’s Cathedral created sustainable building systems and functionality with a focus on long-term, change-ready solutions. In this way, leadership invested in not only “the most sustainable, cost-effective, long-term options,” but also those “that best align with the greater good of the city, community and earth— not just today, but for generations to come.”

Tashjian Bee and Pollinator Discovery Center, University of Minnesota Landscape Arboretum | MSR Design | MSR Design

The Tashjian Bee and Pollinator Discovery Center is a multi-functional public education facility in Chaska, Minnesota. It provides learning opportunities for children and adults about the lives of bees and other pollinators, their agricultural and ecological importance, and the essential, fascinating, and delicious ways our human lives intersect with theirs. Along with their importance to flowering plants, honey bees and other pollinators play a crucial role in the production of the food we eat. However, the health of pollinators is endangered by pesticide use, lack of forage, destruction of nest habitats, and colony collapse disorder. Serving as the outreach arm of the University of Minnesota’s Bee and Pollinator Research Lab, this new 7,530 square-foot center contains exhibit space, a multi-purpose learning lab, a demonstration apiary, and a honey extraction room. Located on a previously abandoned historic farm site at the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, the Bee Center is the first building of a new campus focusing on sustainable farm-to-table education.

The architect developed a master plan for this new campus with the 120-year-old Red Barn as its heart and future event center. The practical beauty of traditional farm buildings inspired the Bee Center’s simple forms, its siting, material selections, and its passive design strategies. The Bee Center’s exposed glulam truss framing is a contemporary response to the wood framing of the Red Barn’s hay loft. The design connects each interior program space to demonstration pollinator gardens, beehives, and future food production plots. The Bee Center strives to serve as an exemplar of its program’s urgent call for human conversation and best practices in our natural environment. Located in an arboretum that is visited by hundreds of thousands of people in all seasons, the Bee Center invites visitors to deepen their understanding of, and connection to, the natural world around them.