Using artificial intelligence (AI) to apply machine learning to planning and constructing buildings is still a theoretical proposition for many AEC firms. But in recent years, as data storage and computational power have expanded, more firms are willing to engage AI as a practical analytics tool. Their ultimate goal for using this platform seems clear: to generate predictive data that provides early hints about future trends and behaviors on everything from interior designs to jobsite safety.

For example, co-working real estate giant WeWork is using AI-driven machine learning to forecast how prospective occupants might use co-working and shared spaces, and to assist its design partners in making more optimal choices. These analyses draw data from the company’s 200-plus locations worldwide.

“We’re trying to understand the right kind of spaces to put into offices, so we’re not wasting space or overusing it,” says WeWork’s Director of Research Daniel Davis, PhD. He adds that machine learning “presents multiple scenarios” and a variety of options.

“We have a lot of simulations in this industry, which the application of this new approach could make less deterministic,” says Alvise Simondetti, Global Leader of Virtual Design at Arup’s London office. “That could be AI’s greatest potential impact on construction.”

Arup is in an “exploratory stage” with AI, Simondetti says, and has had successes applying machine learning technology. These include a project in New Zealand, completed in 2016, where a joint venture of Arup and Jacobs was commissioned to create the reference design for a proposed 18-mile Auckland Light Rail route with 24 stations. Normally, identifying utility clashes on such projects is a tedious and costly manual exercise. To automate the process, the design team developed a “neural network” that consolidated the utilities data with information about the light rail’s asset features. A machine-learning algorithm was applied to reduce the need for further manual assessments.

The result: The team’s design reduced the number of potential overall clashes to 443 from 5,183, and saved an estimated 790 engineering hours, according to Josh Symonds, Arup’s Australasia Regional Leader of spatial and data engineering.

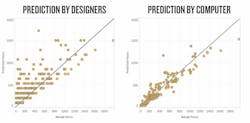

WeWork has been using AI to diagram the basic process for predicting meeting room usage. The graph boxes (at top) compare the actual number of hours a meeting room was occupied with the hours predicted by the company’s designers (top, left) and its neural network algorithm (top, right). The neural network is 40% more accurate than humans at predicting the frequency of usage by occupants. The illustration (above) shows (from left to right) the data inputted into the model, the data flowing through the neural network, and the prediction about room usage. WeWork.

Image recognition helps organize field data

Ideas about AI’s usefulness as a cognitive tool and its broader impact on society have been debated for decades. And there’s been plenty of hype surrounding AI’s application for construction, say industry insiders. “The technology only works on certain problem types, and it requires really skilled people to use it,” cautions Davis.

Stacy Scopano, Vice President of Innovation at Skanska USA’s Atlanta office, agrees, noting that AI and machine learning are still in their “very early days, both inside and outside the industry.”

He thinks the biggest impediment to this technology’s progress continues to be the construction industry’s haphazard approach to data collection, an opinion shared by every person whom BD+C interviewed for this article. The general consensus among experts is that machine-learning algorithms need a ton of data to learn from.

Scopano acknowledges that “unwinding and rationalizing” Skanska’s own data is a “Herculean task.” To that end, the firm has launched a number of pilot programs that include a strategic partnership with Smartvid.io. The pilot supports the use of Smartvid.io’s cloud-based platform at select Skanska jobsites to test and deploy machine-learning software for organizing field data such as drone photography and videos.

Both Scopano and Josh Kanner, Smartvid.io’s Founder and CEO, anticipate significant benefits in the AEC industry from using AI to analyze data generated from speech and image recognition.

Finding the right “dot”

Simondetti points out that humans’ analytical skills are hindered by their tendencies to come up with one solution and focus on validating it to the exclusion of alternatives. The appeal of AI and machine learning for AEC firms, he and others contend, lies squarely on the technology’s ability to offer myriad choices for a given task or design, and to optimize those choices without prejudice and within parameters such as efficiency, cost, and time.

“We’re all stuck in a world of ‘one dot,’” says Rene Morkos, PhD, a second-generation engineer and Founder and CEO of ALICE Technologies, in Menlo Park, Calif., whose software platform applies AI to construction engineering and planning. “This technology lets you find the best dot when it comes to labor, equipment, and materials, so you can start to understand the implications of decisions.”

Morkos estimates that his company has worked with 70% of the industry’s 25 largest engineering and construction companies, including Mortenson Construction, which first piloted the ALICE AI platform for scheduling management on a healthcare project in Denver.

Ricardo Khan, Senior Director of Innovation in Mortenson’s Minneapolis-St. Paul office, says his firm went through the standard scheduling process for this project, and then ran it again through ALICE to develop a scheduling sequence. ALICE produced 66 million 4D options and 22 different parametric sets and construction strategies, based on time and cost. ALICE shaved 84 days from the project’s original 540-day schedule.

Mortenson rejected the shorter schedule because, says Khan, it would have added “significantly” to the project’s cost. (Morkos elaborates that the cost increases, in part, were related to accelerating steel shipments and using more construction cranes to hit the scheduling target.)

But, at the very least, this pilot “confirmed that ALICE can do what it claims,” says Khan. Mortenson is now testing ALICE on projects in Chicago and Seattle, where the platform is creating schedules that Mortenson’s personnel then rationalize against budgets.

“We are focusing on change leadership to build a pathway to get full implementation of AI, and ALICE is one of the bridges,” says Khan.

(Khan and Morkos will present their findings and takeaways from implementing AI on construction projects at BD+C’s Accelerate Live! AEC innovation conference, May 10, in Chicago. Purchase tickets at: AccelerateLiveBDC.com.)

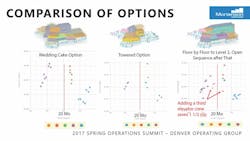

Mortenson Construction has been testing Alice Technologies’ AI platform for project management. For a healthcare project in Denver, the platform provided myriad options for two different exterior designs and how crews for different stages of the project could be optimized to reduce the overall construction schedule. The platform tracks and quantifies crew utilization, working and idle costs, working days, and tasks. Mortenson is conducting further tests of this platform on projects in Seattle and Chicago. Mortenson Construction/ALICE Technologies.

Compressing tedious tasks

Another construction firm that’s digging deeper into AI is McCarthy Building Companies. It recently embarked on an evaluation of a software platform from Pype, which filters project specs through a machine-learning algorithm to come up with submittal register items that McCarthy would provide to its subs and design partners.

David Burns, Director of Innovation and Field Applications in McCarthy’s San Francisco office, says his firm tested Pype on four projects, one of which entailed 3,000 pages of specifications. An engineer on that project spent three weeks coming up with the submittal logs. With Pype, it took just three hours to determine 1,200 items, which Burns notes were 99% accurate, based on another several hours of manual checking for quality control.

All told, the projects that McCarthy ran through Pype—which it integrated with Procore’s construction management software—saw efficiency gains between 200% and 500%, even with quality control factored in. Burns notes that the engineer involved in the project that realized the 500% gain was a “technology hater” until he saw the light when the culling process that once took 40 hours was reduced to five minutes, with another eight hours of QC.

Burns’ team approved its evaluation of Pype in December, and in late February got the thumbs up to move forward from McCarthy’s advisory board. When BD+C interviewed Burns in early March, McCarthy was considering a broader application of Pype for multiple projects over the next 12 months.

McCarthy has also looked at machine learning that draws on image recognition data. Of particular interest are Smartvid.io’s products to track jobsite safety and spot out-of-kilter activities, such as when rebar continues to be capped improperly or when crew members persistently don’t wear gloves or safety equipment.

Several sources interviewed for this article talked about using AI and machine learning to reduce risk. About 18 months ago, Autodesk delivered a pilot solution that added an AI layer to its BIM 360 field app. That souped-up product, called Project IQ, prioritizes what problems and issues on a jobsite need the most immediate attention each day.

“It’s like having a smart assistant,” explains Pat Keaney, Director of BIM 360 Enterprise Products in Autodesk’s San Francisco office. The objective, she explains, is for a project engineer or superintendent to be able to check into the program for risk management, “much like they would check the weather.” The program provides patterns and trends that might not be immediately apparent, and creates models that classify and prioritize various risks, such as water penetration.

BIM 360 Project IQ is also using safety data to apply machine-learning models to categorize issues by 40 leading safety hazards that can lead to jobsite fatalities. This is helping project managers focus their crew training measures.

A sample of ALICE Technologies’ AI-driven construction schedule analysis conducted for a healthcare project in Denver. ALICE shaved 84 days from the project’s original 540-day schedule. Mortenson Construction/ALICE Technologies.

Intersecting with other technologies

AI has the potential to go in all kinds of directions. In February, IBM and Unity entered into a partnership to integrate the former’s Watson AI platform into Unity’s virtual- and augmented-reality gaming engines. And last month, Microsoft Co-founder Paul Allen announced his plans to spend $125 million to teach common sense to AI-driven machines.

As for the construction field, Autodesk’s Keaney, for one, thinks AI’s impact could be “boundless.” But she and other industry sources concede that exploiting AI and machine learning to their maximum will require AEC firms to do a much better job at collecting and aggregating data about their projects, operational procedures, trade partners, and clients.

Mortenson’s Khan believes that to fully leverage AI and machine learning in construction, trades must be involved in the process upfront. And one way to do that would be to get subs to lower their resistance to wearable sensors, which Khan and other AEC sources believe could play a major role in feeding AI machines with information.

Burns singles out Triax Technologies’ Spot-r sensor that clips onto a worker’s belt. The device has several safety-related features such as an accelerometer to detect falls, and a distress button. It also syncs electronically to a cloud-based reporting dashboard that provides real-time insights into worker activity.

The volume and quality of data that the industry gathers and shares ultimately will determine whether AI and machine learning can be used broadly and dependably for predicting and planning for outcomes and behaviors. This is what most AEC AI experts want to happen, but they concede that it’s still years away.

“You never really know what’s causal” when it comes to productivity and profitability, observes Scopano of Skanska. “Once we clean up and steward our data, we’ll be able to see better where we’re good and where we’re lucky.”