THE PANAMAX EFFECT: Panama Canal expansion could trigger an East Coast construction boom

Two months ago, the town of Summerville, S.C., broke ground on a $19 million, 307,000-sf shell building (expandable to 923,000 sf) at the Charleston Trade Center, a 750-acre shipping complex with access to the Port of Charleston.

At the same time, the South Carolina Ports Authority has embarked on a $1.6 billion program that includes the construction of a $750 million terminal and $350 rail line at the old North Charleston Naval Base. The Ports Authority is also conducting engineering studies to enable dredging of the port to 52 feet from its current depth of 45 feet. The dredging, at a cost of $509 million, would make Charleston the deepest harbor on the East Coast.

BD+C MOVERS AND SHAPERS

The People, Institutions, and Movements that are influencing design and construction in the U.S. and around the world.

Dan Gilbert – Detroit's Catalytic Converter

Judith Rodin – Crusader for Resiliency

Bruce Katz – Urban Evangelist

Millennials – The Disruptors

Alloy LLC – Vertical Integrator

Jerry Yudelson – Green Giant

The PANAMAX Effect – The New Panama Canal

Theaster Gates – Real Estate Artist

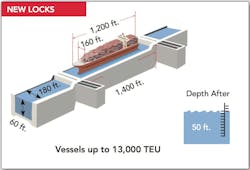

Activity of this kind is occurring up and down the Eastern seaboard and Gulf Coast in anticipation of the opening of the expanded Panama Canal on June 26, the first expansion of the waterway since the canal became operational in 1914. The $5.25 billion construction program added a third set of locks and widened and deepened Gatun Lake, various access channels, and the channel that cuts between Panama’s mountains.

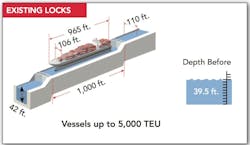

Currently, only ships with cargo no greater than 5,000 TEU (the equivalent of a 20-foot container) can traverse the Panama Canal. The expansion will be able to handle ships up to around 13,000-TEU capacity. The Panama Canal Authority estimates that allowing 12 to 14 larger vessels per day to pass through the new locks would double the canal’s annual activity to 600 million tons of cargo.

Panama Canal traffic flow has been rising in recent years. Last year, a record 340.8 million cargo tons made the 48-mile passage through the channel. The Panama Canal Authority projects that figure to rise to 360 million tons in 2017. But with 56% of the new cargo vessels on order being built to larger-capacity “post-Panamax” standards, expanding the canal became a competitive necessity.

As more traffic starts moving through the canal, U.S. ports that are already congested will have to find ways to become more efficient. In its “2016-2020 Port Planned Infrastructure and Investment Survey,” the American Association of Port Authorities reported that its members and their private-sector partners would spend nearly $155 billion on port-related freight and passenger infrastructure improvements over the next five years. Five years ago, the AAPA survey found that only $46 billion in spending was anticipated.

Whether the canal expansion will shift cargo traffic to East Coast and Gulf Coast ports is an open question. But a report by Boston Consulting Group and the supply-chain provider C.H. Robinson estimates that, by 2020, as much as 10% of container traffic arriving from East Asia could shift from western ports to their eastern rivals.

Where container ships dock often depends on the preferences of vessel operators, some of which own terminals at ports, says Steve Fitzroy, Executive Vice President with the Economic Development Research Group. He is one of the coauthors of a study on the impact of the Panama Canal expansion on ports and cities for the U.S. Maritime Administration.

Several East Coast and Gulf Coast ports are positioning themselves to be the destination of choice for larger vessels. Most new spending—in Charleston, Fort Lauderdale, Miami, New Orleans, and Savannah—revolves around dredging, infrastructure upgrades, and improvements in connections with rail and transit facilities.

In April, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey weighed in with an RFP for a 30-year master plan for its water port system, the country’s third largest. The goal: to surpass the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach in cargo volume.

The Port Authority is already spending $5 billion to raise the height of the 5,780-foot-long Bayonne Bridge, which connects Bayonne, N.J., to Staten Island, N.Y., to 215 feet, from the current 151 feet, to accommodate taller vessels. The Port Authority is also making improvements to the port’s water- and landside connections. “On-dock rail and automation are going to separate the men from the boys,” predicts Fitzroy.

to open up more trade opportunities for Eastern Seaboard and Gulf Coast ports. Click to enlarge.

MORE LANDSIDE DEVELOPMENT?

Will greater cargo volumes at East Coast and Gulf of Mexico ports lead to a spurt in nonresidential development and construction for surrounding communities? It’s probably going to be some time before post-Panamax vessels will be dropping anchor at eastern and southern U.S. ports. Real estate developers likely will wait and see which ones attract the most activity before investing in new construction. But ever since the Mayflower bumped into Plymouth Rock, ports have fed local economies.

Consider Houston’s harbor. Robert Kramp, CBRE’s Director of Research and Analysis, says more than 1.18 million jobs and $265 million in annual economic activity in Texas can be attributed to the port of Houston. Stepped-up port activity from the Panama Canal expansion could have “an echoing effect” on commercial real estate (notably retail and multifamily housing) and on healthcare, government, and education, says Kramp.

STIRRING THE WATERS

Western ports are preparing for growth, too, as BD+C's John Caulfield reports.

Law firms, insurance companies, trucking services, and others in the supply chain also may wish to locate near ports.

The industrial sector could be the earliest beneficiary of stepped-up port traffic. Kramp notes that, over the past five years, developers have built 382.2 million sf of warehouse space in the U.S., largely to handle the explosive demand in shipping products from ecommerce. Much of the newer warehouse construction has been in markets like Atlanta, Chicago, Cincinnati, Columbus, Memphis, and Kansas City that are nowhere near deep-water ports and rely primarily via rail.

Many of the products purchased online come from manufacturers in China and elsewhere in the Far East. The net result, says Kramp, is that “the expanded Panama Canal is mostly going to be used to get these goods to local business and customer markets faster, cheaper, and easier than ever before.”

Editor's Note: After this story was posted, the New York Times published an extensive investigative article [www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/06/22/world/americas/panama-canal.html] that raised questions about the Canal expansion's capacity to actually handle Panamax-size vessels. Among the problems the Times cited include design and construction flaws and defects, dredging depth and lock width, and the availability of water.