When Minnesota passed the nation’s first law permitting charter schools, in 1991, no one could have predicted that more than six thousand such schools would be operating 22 years later. Nor could anyone have known that 18 cities would have at least 20% of their students enrolled in charters.

Today, charter schools are educating just under 5% of public school children in the U.S., according to the National Alliance of Public Charter Schools (www.napcs.org). But don’t let that 5% figure fool you: Demand for charters is exploding, even as many public school districts are closing schools. In Massachusetts alone, 45,000 children are on waiting lists to get into charters, according to the Massachusetts Charter Public School Association (www.masscharterschools.org).

Charter schools have come a long way in just over two decades. Forty-one states and the District of Columbia have laws recognizing charters, and resistance to charters by public school administrators and teachers’ unions has diminished over the years. Private-sector developers have moved into the field, and banks have become a bit more comfortable lending to charters for capital projects.

Despite this progress, getting schools built remains a daunting task for charter operators. Charters get funding on a per-pupil basis for day-to-day operations from the state or their local school district, but the burden of raising the money for capital projects invariably falls on the charter operator. According the National Charter School Research Project, “scarcity of facilities” was listed by 89% of charter management organizations as the single greatest external barrier to their growth.

ALSO SEE: 6 funding sources for charter school construction

Competition for grants, loans, and bond financing among charter schools is heating up, so make your clients aware of these potential sources recommended by experts we consulted for our charter schools report. Read 6 funding sources for charter school construction.

Most charters can only afford to allocate about 14-15% of their budgets to facilities, compared to 22% or more for public schools. Typically, charters will start with one or two kindergartens in leased space and move up a few years later to a K-3 in a renovated space. The real test comes when the charter becomes successful enough to consider building its own facility.

That’s where you come in. Before you get too excited about this opportunity, however, heed the advice of veteran AEC professionals and charter operators consulted by the editors of Building Design+Construction.

1. Learn to recognize the unique characteristics of charter school clients

“Charter starters” come in three basic forms: the disgruntled public school teacher or administrator who believes he or she can educate children more effectively than the public schools; the business executive who sees the free market as the salvation of the education system; and anxious parents desperately seeking a better education for their children. Look for strong representation from all three groups in any charter organization you’re getting into bed with.

2. Keep in mind that a charter operator’s first concern is the education program

With public schools, the design must meet preset parameters, notably square footage per student. These requirements are usually administered by officials with no direct involvement in the school, whereas charter operators invariably have a hand in every aspect of curriculum and operations. “Charter operators tend to be focused on making the space work toward the needs of the program,” says Karl E. Jentoft, Principal with TenSquare LLC, Washington, D.C. That level of involvement can, as we shall see, be both a curse and a blessing.

3. Do your due diligence to avoid getting burned

“You can hit a charter school that really doesn’t know what they’re doing, so do your homework before you get into bed with one,” says Christine Schlendorf, AIA, Principal with Perkins Eastman (www.perkinseastman.com). “Usually the financing for their buildings is dependent on CDs being complete, so we want to be paid before that. The charters we’ve worked with have been very responsible.”

The National Association of Charter School Authorizers (www.qualitycharters.org) is the private nonprofit group that sets standards for half the nation’s charters. Authorizers vet charters’ education programs, staffing, and business plans—valuable information you should review before taking on a charter client.

“Meet their board and staff,” advises charter facilities consultant Jentoft. “See how well they’re doing attracting parents. If they’re not educating kids, the parents will vote with their feet.”

At Boston Renaissance Charter School, HFMH Architects converted a warehouse into a complex of spaces—two gyms, two dance studios, a cafeteria, and two raised music rooms. These activities are separated by partitions which, when pulled back, create an assembly space that can host a thousand people for a graduation or fundraiser. “It’s the most intensely flexible space we’ve every done,” says HFMH’s Pip Lewis. The K-6 school embraces a “whole child” philosophy—foreign language (Mandarin as a second language), dance, fine arts, vocal and instrumental music, technology, and martial arts—espoused by Superintendent/CEO Roger F. Harris, PhD, a former Boston Public Schools principal. Photo: Anton Grassl/Esto / Courtesy HFMH

4. Choose the right partners for your charter team

“Experience counts,” says Jentoft. “If you’re an architect looking to get into charters, partner with a contractor with a track record in charters. If you’re a contractor looking at charters, partner with an experienced charters architect.” Populate your Building Team as much as possible with firms that have charter chops. “Find consultants who have done charters with the school district and know the district’s standards,” says Brianna García, Charters Executive, Los Angeles Unified School District.

Choose partners with deep pockets, because you might not get paid for six months. “If we’re going to finance some of the design and construction up front, we look pretty hard at the charter’s financing and credit standing,” says Tom Rogér, Vice President/Project Executive, Gilbane Building Co. (www.gilbaneco.com). “We don’t want to be the last one paid.”

5. Help your charter client find the perfect property

This is a crucial step, and your expertise can prevent a disaster. “The key is finding the right property,” says Pip Lewis, AIA, LEED AP, Principal with HFMH Architects (www.hfmh.com). “We have dissuaded many rosy-eyed charter operators from buying properties that had bad column spacing or severe zoning restrictions,” says Lewis.

Patricia Saldaña Natke, AIA, Principal in Charge at UrbanWorks (www.urbanworksarchitecture.com), a Chicago firm that has conducted early feasibility studies for charters, says, “You have to warn them about the risks of building codes and help them with ADA accessibility, sprinklers, parking requirements, structural elements, and student drop-off areas.”

Don’t limit your search to vacant public or parochial schools. Warehouses, old mills, car dealerships, nursing homes, strip malls, bowling alleys, grocery stores, even seminaries—all have been adapted for reuse as charter schools by AEC experts consulted for this article.

6. Look for space in a charter incubator—or help create one

High-tech startups often share costs in an incubator facility until they’re ready to go out on their own. That concept has spread to charter schools.

CONTRACTORS: Be prepared for delays in financing projects

“Starting off, you’ve got a client who’s really squeezing pennies, and that affects your choice of materials,” says Tom Rogér, Vice President, Gilbane Building Co., whose projects include Amistad Academy, in New Haven, Conn., and a new charter on Governors Island in New York. “For a public school, we’ll use materials that will last 50 years, but charters are not looking at life cycle costs. They’re thinking maybe six months ahead.”

Rogér says that as a Project Executive, he wants to be involved early in the design process. “The architect is doing his best to satisfy the owner, but my experience is that a lot gets lost in that discussion that can generate costs,” he says. “The teachers may want a chem lab, which is expensive. Maybe all they really need is a general science room.”

Rogér prefers working with a designer who has charter school experience—“someone who’s very efficient and willing to make compromises on costs and aesthetics.” To that end, he uses Gilbane’s proprietary tool, the “Cost Advisor,” which provides cost data from more than 100 recent school projects. “If the owner has $10 million and the first cut is $15 million, you’ve got to change the program right up front,” says Rogér. “It’s our job to make the best use of the charter’s money.”

In Washington, D.C., Perkins Eastman worked with the nonprofit social agency Building Hope to create such an incubator at the decommissioned Birney School. “It’s a kind of gestating program, where you have a couple of small charters in different wings under the same roof, sharing food services, a cafeteria, and assembly space—the D.C. government even provides a nurse,” says Sean O’Donnell, AIA, LEED AP, Perkins Eastman’s K-12 Market Sector Director. One of the charters, Septima Clark, is looking to find new home; the other, Excel Academy, is preparing to occupy the whole incubator.

7. Help your clients locate financing sources

Charters have three primary funding sources: 1) traditional bank financing (i.e., a loan); 2) rated bonds, whereby the charter uses its per-pupil revenue stream to get underwritten for tax-exempt bonds by an investment bank like Piper Jaffray (www.piperjaffray.com); and 3) lease with an option to buy, where a developer builds the school and leases it back to the charter.

8. Brace for pushback from the local public schools

While 41 states and the District of Columbia have laws granting charter schools access to leased space in public schools or the right to purchase closed schools, only 14 have policies to implement those rights, according to the NAPCS.

The most cooperative states, says the NAPCS, are Alaska, California, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Louisiana, New Mexico, South Carolina, and the District of Columbia, but cooperation can vary from district to district, especially in older cities.

For example, Boston has shuttered a dozen or so old school buildings in recent years, yet “there are a lot of charters looking desperately for space, but the city bureaucracy is hesitant to let them use the schools,” says HFMH’s Lewis, whose firm has numerous charters to its credit.

Don’t assume, however, that all public school officials will shut you out. “We, too, want the best schools for the kids,” says LAUSD’s García. “So knock on our door and we’ll help you.”

García says she routinely pulls together staff from multiple LAUSD departments to answer technical questions and help charters with specifications. “Check in with us, so that when something comes up that we’ve never encountered before, we’ll have that relationship, and we can work it out.”

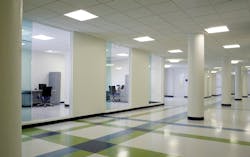

Teachers at United Neighborhood Organization suggested the idea of creating offices with visual access to the corridor and classroom, so that teachers could stay in contact with their students while providing an extra pair of eyes on the hallway. Two teachers from the same grade share an office to foster collaboration. Sprinklers are focused on the glass to provide a one-hour fire-rating. Photo: Anton Grassl/Esto / Courtesy HFMH

[pagebreak]

9. Don’t hesitate to educate the educators

“They’re not builders. They’re looking for guidance: Here’s my pot of gold, what can I get for it?” says Ronald Corrado, Project Executive, Turner Construction Co. (www.turnerconstruction.com).

Corrado, who has worked with Friendship Charter Schools and KIPP Public Charter Schools in Washington, D.C., says 50-60% of his projects have been design-build or design-assist. “These projects work well with having the contractor tied to the architect,” he says. “We occasionally have to tell a client that, for example, there’s no way we can do that curtain wall, and here’s why. It saves a lot of time, and it’s good for the budget.”

However, you must also do your part to help charter clients realize their goals. “With charter operators, there needs to be a lot of listening up front,” says Phil Nemeth, AIA, LEED AP, Managing Principal, HMC Architects (http://hmcarchitects.com). Adds HMC Managing Principal Steven Prince, Assoc. AIA, “You have to spend time up front to understand their business model.”

10. Make sure your design allows for additional income streams

For the Foxboro (Mass.) Regional Charter School, a $15 million public middle/high school that opened last September, HFMH Architects increased the size of the new gymnasium well beyond the needs of the anticipated 1,200 students. The reason: The school had cut a deal with a local sports club to lease the space at night and on weekends—an income stream that’s more than paying its way.

11. Tutor your charter client in the basics of scheduling

Neophyte charter operators simply don’t appreciate the amount of time it takes to design and build a school. “They come to you in April and say they need a 20,000-sf space by August, and they haven’t even hired the architect!” laments Gilbane’s Rogér.

Late delivery is not negotiable, says Turner’s Corrado. “If you can’t figure out how to meet the schedule, you’ve got to be honest and help them make the decisions they need to make right now. The endgame doesn’t change. It’s game on, go!”

Charters don’t have the luxury public school districts sometimes have to be able to shift children around for a few weeks. “If they don’t open on time, it could be catastrophic,” says Jentoft, the charter facilities consultant. “The parents will just take their kids elsewhere. It could put their whole program in a death spiral.”

12. Expect to do much, much more with much, much less

For charter construction, figure you’ll have 65-70% of the space and 65-70% of the budget per square foot that you’d have with a comparable public school. “In New York State, where I’m currently working, you can pay $250-300/sf for a public school,” says Gilbane’s Rogér. “You throw that at a charter school and they’ll laugh in your face.”

Can it be done? Yes. In Castle Rock, Colo., Hutton/Cuningham Group (www.huttonarch.com) is putting the finishing touches on the 80,000-sf Aspen View Academy (PreK-8). “We broke ground last November and it will be ready for 700 students this summer,” says Paul C. Hutton, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP BD+C, Principal. “We’re going to bring it on line in half the time and at half the cost that the local school district could have done.”

While some charter schools, especially those whose operators are new to the game, are still being built on the cheap, it is also the case that many of the established charter operators are building facilities that compare favorably with well-funded public schools, including full gyms, foodservice facilities, assembly spaces, and playgrounds.

13. Make every space work twice as hard

“You have to learn what spaces they think they need, and then you have to talk them down to a reasonable level and be innovative, because every space has to serve more than one purpose,” says Perkins Eastman’s Schlendorf.

Charters often have after-school programs, community meetings, adult education, and health programs going on six or seven days a week. “They don’t shut down at three o’clock,” says Mark McCarthy, AIA, LEED AP, Principal, Perkins Eastman. “In a traditional school the teacher owns that classroom; in a charter, someone else uses it at night and on weekends, so every room has to do double duty.”

One common solution: the “gymacafetorium,” a flex space that can be quickly reconfigured into a gymnasium, eating space, or auditorium/meeting room.

American Academy PreK-8 charter school in Castle Pines North, Colo., 20 miles south of Denver, designed by Hutton/Cuningham Group. While the majority of charter schools nationally are located in cities, the Denver metro has substantial charter activity in its fast-growing suburbs to the south. Photo: Raul J. Garcia / Courtesy Hutton/Cuningham Group

14. Step outside your comfort zone

Global Village Academy, a language-immersion K-8 charter in Aurora, Colo., wanted a building that reflected the international nature of the program, “so we did some fun stuff with color and tilt-up and sealed concrete floors,” says Adele Willson, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP, Principal, Slaterpaull Architects (www.slaterpaull.com) “That’s not something we could have done for a neighborhood public school.”

Hutton/Cuningham Group has designed blue roofs for Denver-area charters: “In our climate, green roofs are not practical, but we do have flash storms.” Hutton says a blue roof can be cheaper to install than a detention basin. He has also experimented with combining low-cost rooftop air-handling units with displacement ventilation to provide improved indoor air quality.

15. Take good ideas wherever they come from

UrbanWorks’ Pat Natke recalls an innovation that came from an unexpected source at UNO, Chicago’s United Neighborhood Organization: “We were at a dinner with the incoming teachers for Galewood School, and they told us they didn’t want the usual wing of ‘teacher offices.’ They wanted to be close to their classrooms, to maintain the connection with their students.”

This discussion led to a floor plan with glassed-in offices flanking the classrooms and extending into the corridor. Each office is shared by two teachers from the same grade to allow for collaboration but also to provide two sets of eyes on the corridor and into the classrooms. To get the required one-hour fire rating for the glass, the designers configured the sprinkler heads to spray the glass.

Natke says the maintenance crew also asked for storage space for their mechanical floor washers. “They also reminded us that we had missed something in the design of the vegetated roof,” she says. The designers quickly amended the roof plan to add a closet for storing shovels and hoses.

16. Design and build in phases to stretch the budget

“Charters move a lot in the first five years,” says charter facilities consultant Jentoft. “They get into that first building and start growing, and then it becomes a question of how to get over the finish line into a new building.” His advice: look into a lease with option to buy, and design buildings that can be completed in phases.

Plan carefully for contingencies, too. “These jobs need to be planned with alternatives that can be added or removed based on the budget,” says Jentoft. “There’s no second bite of the apple. You can’t go back to the school board for more money.”

[pagebreak]

17. Don’t throw out the kitchen with the bath water

A full kitchen is a big-ticket item—$150,000 to $170,000. “That’s one of the first things charters let go,” says Hutton/Cuningham’s Hutton. Only about one-fifth to one-third of charters have kitchens that qualify for the National School Lunch Program, and “that’s a deterrent to low-income kids attending your charter,” says Jim Griffin, President, Colorado League of Charter Schools (www.coloradoleague.org).

But the impact goes deeper. Federal Title I reimbursements and state subsidies are tied to the free/reduced lunch program. If you hire a caterer to bring in lunch, you don’t get reimbursed by the government, says Griffin. No full kitchen, no reimbursement—a double whammy.

Due to first-cost constraints, you probably won’t win the battle for a full kitchen, but you should advise your charter operator as to the consequences of not having one.

Hutton, who is the Incoming Chair of the AIA Committee on Architecture for Education, sees a similar problem with the paucity of gyms in charters. “Yes, I understand they have to make compromises, but with the crisis in childhood obesity and diabetes, I would urge charters not to cut those facilities.”

Boston Renaissance Charter Public School, a 105,000-sf K-6 serving 885 students in the Hyde Park neighborhood. A 15,000-sf addition links a 70,000-sf heavy timber/masonry mill building (shown here) with a 20,000-sf mid-20th-century warehouse. HFMH Architects led the team, including Garcia Goluska DeSousa Consulting Engineers (MEP) and Suffolk Construction (CM at risk). Photo: Anton Grassl/Esto / Courtesy HFMH architects, Inc.

18. Make the owner’s rep your buddy

Slaterpaull’s Willson says quite a few of the more than 30 charter schools she has designed hired owner’s representatives—and she’s glad for it. “Some of the ORs have targeted the charters as clients and understand their budgets and operations,” says Willson. “They can help navigate the process, especially when there’s a charter group that needs that kind of help.”

19. Keep building systems simple

Most charters don’t have the facilities staff to operate sophisticated building automation systems, says Slaterpaull Architects’ Willson. “We’ll still fight for daylighting systems and occupancy sensors, because those dollars come back to them in energy savings, but we can’t always justify the cost for higher-end mechanical systems.”

20. Let the building inspire the community

Charter operators with a strong community-service mission want buildings that provide a source of aspiration and inspiration. “Our overriding goal is to make an impact, not only with the academic success inside the classroom, but also with how our buildings project into the community,” says United Neighborhood Organizations’s Andrew Alt, Vice President, Real Estate and Facilities. “You can deliver a precast box, or you can do something that the community is proud of and has some ownership in.”

UNO, which serves Chicago’s 800,000 Hispanics, has 13 schools completed or in the works. “From an aesthetic point of view we hope that each of our buildings will have a positive influence on the surrounding neighborhood—well landscaped, well maintained, even a deterrent to crime,” says Alt.

21. Step in and help charters with long-range master planning

“A lot of the people involved in charters are looking at immediate needs, and they may not have experience planning for future growth,” says Russell A. Sears, AIA, LEED AP, Principal, Russell Sears & Associates (www.sears-architects.com). “After reviewing their existing program, we talk about future enrollment, capacity, and curriculum, and then we look at the site—things like parking, and where we could put new buildings. They may have an addition on their wish list, and I may explain how that addition could hurt access to the site, or create an eyesore, or cut off the potential to put in a new building later on.” At that point, it’s time to discuss real options. “It’s a great opportunity to be creative,” says Sears.

22. Build green, but don’t go overboard

Most charter operators want to be green but usually have to settle for the low-hanging fruit—low-VOC materials and so on, says TenSquare’s Jentoft. Some want to be able to add green components later, when they have more money. “They always ask for a green roof but they usually can’t afford it, so we make sure the structural components and access to water are there for when they’re ready,” he says.

LEED certification for charters varies. New York City doesn’t require it for charters but Harlem RBI DREAM Charter is going for it, says Schlendorf. The District of Columbia requires LEED (or an alternative such as CHPS) for any project getting capital funding from the city. “LEED Silver is usually within striking distance,” says Perkins Eastman’s O’Donnell.

HMC’s Prince says the charter operator has to set the sustainability threshold. “LEED Platinum may not be their business objective,” he says. “If they just want to pick the right lights and low-VOC materials, that’s their decision.”

Of course, not everything green works. UNO did an extensive green roof as a learning space at its Veterans Memorial campus. “With six months of cold in Chicago, we’ve gone to green trays with a live load,” says Alt, UNO’s Vice President for Real Estate and Facilities. The charter operator has also ruled out geothermal as too expensive. Yet all six of the charters it owns outright have earned or are seeking LEED Silver or Gold.

23. Try new materials

At UNO’s Galewood charter, “We wanted to create the sense of how UNO was rising at a cosmic rate,” says UrbanWorks’ Partner Meggan M. Lux, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP BD+C. The firm designed a dramatically upward-sweeping roof and specified a coated composite panel faced with natural wood veneer called ProdEX, from Prodema (www.prodema.com).

The problem: ProdEx had never been used for a school exterior in Chicago. “We had to prove that it was not making the wall less safe than more conventional materials,” says UrbanWorks’ Partner Rob Natke, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP BD+C. With the manufacturer’s help, the firm was able to get City Hall to approve the product.

Did we miss an important point about charter schools? Send your suggestions to: [email protected]. We’ll publish the best contributions.