Hurricane Matthew has brought renewed attention to the importance of adaptive strategies in the planning and future-proofing of our urban waterfronts. Adaptive planning can address a variety of objectives, including reducing the impact of a direct storm event such as Hurricane Katrina, avoiding damage from storm surges such as Hurricane Sandy and mitigating sea level rise. Many coastal cities are thinking broadly about their infrastructure, combining open space networks with sewer and water planning to improve adaptive performance in extreme weather and elevate the general quality of life for residents on a day-to-day basis.

An Incentive to Act

The picture above shows a portion of the Embarcadero in the fall of 2010, when storm surge combined with a king high tide resulted in an overtopping of the sea wall. The event caused alarm and concern for residents and city officials. The Port Authority had long recognized that much of the coastline on the San Francisco side of the Bay was vulnerable to damage from sea level rise. Analysis suggested that finger piers and portions of the sea wall could be subject to tidal uplift and might not have a fully functional life by the end of the century.

A Leading Voice

A proactive response has already begun. In the last 7 years, SPUR (formerly known as The San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association) published a series of articles on sea level rise and the future of the San Francisco Bay area. According to their research, “In the last 10 to 15 years, the rate of global sea level rise has increased by about 50 percent, and is now averaging 3 millimeters per year. In California, we are very likely to experience a sea level rise of 16 inches by 2050 and 55 inches (1.4 meters) by 2100, and (probably) much more after that.”

Rising tides are due to multiple factors, including expansion of oceans from rising temperatures and melting glacial ice. Approximately 40 percent of California’s land drains to San Francisco Bay, and storms and flooding will last longer at the coastal edge than in higher-elevation regions. Under existing conditions, the combination of high tides, storm surges and river flooding can raise water levels in the Delta. As sea levels rise, low-lying areas protected by already fragile levees will be even more at risk.

Building a Coalition

In 2015, SPUR formed a group of interested citizens, nonprofits and city and community organizations to study the impact of sea level rise in detail. They hired a consortium of scientists, engineers and designers led by ARCADIS, a global expert in coastal adaptation strategies. The scope of the study was to understand in greater detail the probabilities of sea level rise in San Francisco and the impact it might have on specific neighborhoods with the overall purpose of proposing a variety of design solutions and implementation strategies. One of the most vulnerable areas in the city—Mission Creek in Mission Bay—was chosen for the study.

“We sought to develop a model for interagency collaboration and knowledge-sharing that the city can use in future work to address sea level rise along its entire shoreline,” said ARCADIS Project Manager Peter Wjisman.

The full study can be found here.

Acutely Vulnerable

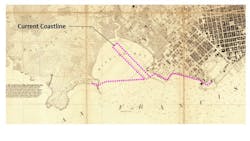

Historic maps in the report show that, until the late 19th century, Mission Bay was a shallow, crescent-shaped wetland and a significant waterway that formed the city’s eastern watershed. Most of today’s Mission Bay development, China Basin and the areas immediately south of the 80 Freeway are manmade. Mission Creek was channelized before World War II as mooring space for navy ships and barges. Years of industry increased Mission Creek’s toxicity. As industrial uses moved to the East Bay after the war, a houseboat community relocated from Islais Creek. In the 1990s, a significant sewer and water treatment facility was built at the base of the Creek. The Mission Bay development is transforming the coastline further south, including providing a home for UCSF campus and the new Golden State Warriors Arena, but the low-lying character of the entire area continues to make it vulnerable to intermittent storm surges.

“If we are going to continue to see such development interest in this portion of the city, it’s essential to consider future investments that prevent damage from rising seas and storm surge while improving water quality and the overall ecology of the tidal estuary,” said Corrine Woods, a Mission Creek houseboat resident.

Project Assumptions

The ARCADIS team selected two scenarios to study in terms of impact upon the area: 52 inches above mean higher high water in 2050 and 77 inches above mean higher high water in 2100. These projections are based on a variety of factors, including projections from 2013 FEMA maps for the area and the 2014 San Francisco Public Utilities Commission and Sewer System Improvement Program Maps, which represent state-of-the-art projections for the San Francisco shoreline.

Collaborative approach

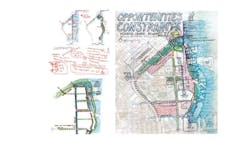

The team included engineers, government officials, sustainability experts, planners and urban designers. Information was gathered from a wide number of sources, including site reconnaissance, GIS mapping and face-to-face interviews with residents and key stakeholders. An open-minded approach was applied to the work, with multiple brainstorming sessions, workshops and opportunities to get input from a wide range of key voices.

Objectives

Driving the work was a series of mutually agreed upon objectives:

- Range of concepts: the study would address both the creek and the adjoining shoreline, looking at options without selecting a preferred alternative

- Creativity: the options developed will be as visual and varied as possible to help generate discussion and imagine potential

- Multipurpose solutions: learning from best practices, flood protection will be integrated into the urban fabric as a multipurpose network of amenities that help to create an attractive and investible city

- Natural ecosystem development: seek opportunities for natural ecosystem and habitat development that enhance environmental quality

- Future Adaptability: all designs should mitigate rising sea levels and storm surge at 2100 projections.

Thinking Big

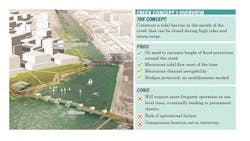

Although conservation of the waterfront is a common desire, the impact of climate change will fundamentally change the waterfront to such a degree that it was necessary to challenge the community to stretch their imaginations beyond the status quo. The design team was able to introduce a number of options that were not immediately obvious for consideration through a best practices approach. The team took inspiration from projects such as London’s Thames Barrier Locks, Japan’s Super Levees and Singapore’s Marina Barrage.

Notation and Refinement

Although San Francisco is a great waterfront city, the experience of the waterfront is often challenged by poor water quality and limited access. A process of presentation, discussion and refinement was employed by the design team. Comments were collected and integrated into schematic designs multiple times for creek and shoreline protection alternatives. Each of the options was presented not only in terms shoreline protection, but also in terms of community benefit and human experience of the waterfront.

Rethinking the industrial waterfront

The study takes a clear-eyed approach to the existing piers and their future. A variety of options are presented, from completely rebuilding the piers to allowing for occasional flooding of the pier and associated pier buildings to even allowing a “strategic retreat” from the current shoreline.

Conclusion

Although comparative studies such as Rebuild by Design often capture the headlines, it does not have to take a major catastrophe for local, state and federal agencies to collaborate effectively. SPUR, city agencies and the local community are proactively studying sea level rise and the potential impacts upon San Francisco’s urban waterfront.

The benefits of thinking about issues of sea level rise NOW are:

- Consciousness raising: Although San Franciscans are generally well educated about sustainability, starting a discussion now about coastal adaptation can build valuable coalitions that can lead discussions about strategy in the future.

- Rethinking the water’s edge: Although the answer in New Orleans after Katrina was more or less to simply build a higher levee wall, we are learning from global examples that through “softening” the urban water’s edge and allowing water into the city in a variety of ways, natural storm events and sea level rise can be accommodated more flexibly and inexpensively.

- New opportunities: Although San Francisco is a great waterfront city, its waterfront is not always great. Allowing the waterfront to change from its history as a working port toward something more nuanced will increase appreciation of the water’s edge, generate land value and open up new development opportunities that help to pay for capital improvements.

- Extending the Brand: While San Francisco is well known as a leader in sustainability, its future waterfront remains in question. Thinking progressively about its options will help it remain competitive in attracting the best and brightest while creating more amenities that improve the quality of life for residents.

- Anticipatory governance: In an era of scarcity, governmental agencies often hold on too long to authority of physical assets it can no longer maintain and suffer through the mounting costs associated with deferred maintenance. With the Port Authority willing to admit it might not be able to maintain all of its piers in the future, it can focus its resources intelligently while appropriately rethinking its business model.

Finally, every major city could benefit from an advocate for progressive planning and environmental issues such as SPUR. By acting as a provocateur, they have effectively started a vital discussion and enlightened decision makers about an issue that might not otherwise be addressed until a catastrophic event such as Hurricane Matthew.

SPUR’s Laura Tam, put it well: “We in San Francisco have perhaps a unique opportunity…to demonstrate what a truly sustainable city and region would look like. If we can’t find a way to create a carbon-neutral way of life here, with all of our wealth, innovation and political support for tackling climate change, then we are lost.”