Last month, Michael Fowler, a Mechanical Designer and BIM Manager with engineer Lockwood, Andrews & Newman, set up a meeting with several of the firm’s practices to discuss how drones might soar into their futures.

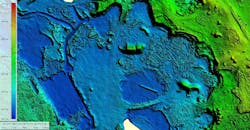

A few months earlier, Fowler caught the drone bug while watching a presentation at an AEC tech event. It showed a prop drone that had been programmed to fly over a square-mile area at Red Rock Canyon, in Nevada. Thirty minutes after the flight, the point cloud data the drone collected was converted into 3D imagery that could be superimposed over U.S. Geological Survey maps.

“What was really interesting to me was the speed of the turnaround” and the accuracy of the images, says Fowler.

The Computer Technology Association expects drone purchases to hit one million units in 2016, a 145% increase from last year. Juniper Research estimates commercial drone sales alone will rise 84% this year to $481 million.

Eager pilots are likely to include AEC firms that see drones as useful tools for surveying hard-to-access structures and sites. Some firms are already marrying drone technology with image-capture tools to enhance their modeling and designs.

FLYING WHERE HUMANS WOULD BE ENDANGERED

Andy Phan, Senior Associate and Director of Visualization with Page, says his firm’s engineers often want to inspect a project from the top of its roof on down. Google Earth doesn’t provide the detail that drones with cameras can show, he says.

Page also uses drones to reinforce its modeling. On high-rise projects, for example, it has worked data captured by drones into the design process to position the building vis-à-vis other buildings on the site.

PBK recently used its $2,000 3DRobotics quadcopter to inspect a church and its surrounding grounds. The drone was able to survey the 18-acre site in 15 minutes, and the point cloud data it delivered was run through BIM software for modeling right on site. Jose Galindo, Director of PBK’s VIZLab, says the drone can get “really close” to a building. “It greatly speeds up the modeling process,” he says.

Thornton Tomasetti has been using drones to help its forensic engineers assess buildings in situations where it is “not safe or even possible for humans to perform an investigation,” says Robert Otani, PE, LEED AP, a Principal with the firm. He says Thornton Tomasetti now combines drone technology with 3D laser scanners for more accuracy on new construction and renovation projects.

Working pro bono, Autodesk in 2014 conducted a proof-of-concept exercise that incorporated drones for the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo. The Air Force had issued an RFP to renovate its Cadet Chapel, which was completed in 1962. Autodesk offered to run the project through various technologies and models to see if the estimated $80 million renovation cost could be lowered.

The chapel was the first project for which Autodesk employed photogrammetry—the use of photography in surveying and mapping to measure distances between objects. It piloted a Phantom 2 Vision Plus quad copter inside and outside the building, and shot 4K video and more than 500 images.

“We got views of the chapel that no one else could have,” including from its roof, 150 feet above the ground, says Pete Kelsey, Strategic Projects Executive at Autodesk. The interior images revealed water damage in the chapel, whose busy booking schedule makes it virtually impossible to shut it down to erect scaffolding for physical inspection.

REGULATIONS ARE SORTING THEMSELVES OUT, SORT OF

Autodesk was more than pleased with the quality of the data collected by the drone. But Kelsey notes that flying inside the chapel was difficult because the GPS system couldn’t be used. He also notes that photogrammetry software “doesn’t like shiny stuff,” and glare compromised some of the images.

Kevin Grover, PE, Regional Technology Lead with Stantec, explains that, regardless of the quality of the camera, glare often results when there are different resolutions between images. Using drones to capture a specific point cloud of water is hard, too, because “it all looks the same.” Drone cameras also don’t like things that move, “even trees,” says Grover.

Stantec acquired its first drone, a fixed-wing model, three years ago, and has used drones primarily for mapping and geomatics. The company is only licensed to fly drones in Canada, where regulations enforced by Transport Canada have been in place for a while.

“You don’t have to be a pilot, and the ground-school course is only two or three days,” says Grover. Stantec’s permit allows it to fly up to 700 feet above ground and within controlled air space.

Grover points out, though, that Transport Canada is updating its regs—due out in 2017—and is likely to align them closer to what the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration comes up with.

In December, FAA issued an interim final rule that establishes registration and marking requirements for small drones used recreationally. Drones that weigh between 0.055 and 55 pounds must be registered.

FAA also launched B4UFLY, an app for iOS devices that identifies airspace where drones are prohibited. The agency said that state or local drone regs shouldn’t conflict with federal rules. At the same time, FAA said local laws prohibiting drones from being used in ways that invade privacy—something the federal regs don’t address—would be acceptable.

FAA is expected to issue its final rules for commercial drone use this summer. Until then, companies must apply for a Section 333 exemption to fly drones. As of early January, FAA had issued roughly 3,000 permits, compared to about 1,000 through early 2015.

“Ideally, we get some consistency and precedent set in the legal forums, as well as an understanding of the liability associated with using this technology,” says Stephen Held, VP and CIO with Leo A Daly.

Despite regulatory concerns, Held says Leo A Daly is excited about the potential for drone use for business development, field services, and photography/video for marketing. He says drones allow more regular and updated aerials for its GIS (geographic information systems) team, as well as scanning that will “snap into our CAD software, saving time establishing existing conditions.”

NEXT STEPS FOR DRONES

In early February, DroneDeploy, a provider of cloud-based drone aviation and image-capture software, introduced a drone-based volume measurement tool. The feature allows users to measure and analyze volumes on maps, such as stockpiles of materials, from any mobile device, at an accuracy level within 2% of traditional ground-survey methods.

Kelsey notes that the first contractual phase of Mexico City’s new international airport project includes large-scale photogrammetry. He sees endless possibilities for drone use in construction. “With the right camera, you can get data at only a fraction of the cost” of other methods, he says.

PBK’s Galindo points to eBee—a fixed-wing drone used for professional mapping that collects geo-referenced digital aerial images with resolutions as sharp as 0.6 inches per pixel—as being “extremely accurate” for land surveys.