Design-build downsized: Applying the design-build method in an era of smaller projects

How small is too small for design-build? This question was asked at last year’s Design-Build Institute of America’s (DBIA) Federal Project Delivery Symposium, and it stumped the panel of federal owner representatives.

Certainly, any project can benefit from the collaborative spirit and cooperative relationships embodied by design-build. But is there a point of diminishing return where the implementation of full procurement and project development processes for design-build just don’t make sense for small projects? And how do we achieve design-build benefits on those types of projects?

This challenge has been brought into even greater focus as federal construction dollars are reduced and there is a greater emphasis on reinvesting in existing building stock, as evidenced by 2014 budgets for most federal agencies.

DBIA recently released research indicating that design-build project delivery represents nearly 40 percent of total market share in the United States, based on dollar value. The federal government was an early adopter of design-build in the 1990’s, with many agencies now procuring up to 75% of their projects through this process. Most federal agencies agree that the surge of BRAC, ARRA, and MILCON work peaking in 2010 could not have been accomplished without design-build in the federal toolbox. State and local governments have quickly followed suit, with 41 states now enabling broad use of design-build.

“This growth of design-build project delivery across geographic regions and building sectors throughout the United States reflects the imperative for cost and time efficiencies in a world of tightened budgets, and that can be achieved through interdisciplinary teamwork, innovation, and effective collaboration,” says Lisa Washington, Executive Director and CEO of the DBIA.

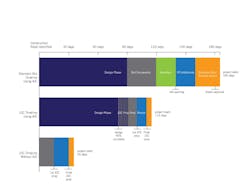

Design-build takes a sophisticated, engaged owner, and while there are clear time savings over other contracting methods, it does require a three to six month procurement process. This makes sense for larger project investments but sometimes smaller projects need to be even more responsive to urgent facility maintenance needs or shifts in government mission. Federal owners have taken a two-prong approach to expediting these types of projects with a design-build methodology by leveraging procurement and process efficiencies available to them.

The federal government has long been a leader in Indefinite Delivery Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) procurement approaches that enable efficient delivery of construction programs. These long-term contracts have helped federal agencies accomplish more construction—from BRAC to ARRA—even as acquisition personnel have been reduced. An IDIQ contract is any type of acquisition where work is delivered under multiple task orders, and the specific project needs are undefined at contract acquisition. An IDIQ must have a defined pricing structure or a competitive process at the task order level, and both of these approaches have been used to leverage design-build construction delivery.

MACCs and MATOCs

The most common and straightforward of IDIQs are Multiple Award Construction Contracts (MACCs) and Multiple Award Task Order Contracts (MATOCs). Especially beloved of the DOD, these contracts come in design-bid-build and design-build flavors, and the primary advantage for both is a smaller pool of pre-selected, qualified contractors that compete for individual task orders. This both reduces the selection process workload at the task order level and creates inherent efficiencies in a reiterative contractor pool that invests in becoming familiar with a particular facility, base, or region, its staff, and its preferred working process.

There are varying degrees of opportunity to streamline the design-build process in MACCs and MATOCs. In the DOD, where there are clear design-build process requirements for MILCON projects—specifically any new construction over $750,000 or life/health/safety upgrades over $1.5 million—it can be challenging for owner and contractor to streamline the design development steps. But enterprising contractors are working to accomplish sensible efficiencies for their government clients while fulfilling process requirements.

Lifecycle Construction Services, based in Fredericksburg, Va., holds several MATOCs and has developed a fast-track design process for smaller projects that compresses front-end civil and structural design packages (or, for renovations, demo and remediation design packages) into a single design review with associated “interim building package”), which can be accomplished in 4-6 weeks.

Lifecycle Construction has successfully used the process on numerous design-build projects for the military. One recently completed project at Fort Lee, Va., compressed the civil and structural design packages to one submission completed in four weeks. This enabled major aspects of the work to begin while the interior design details were being finalized. The successful implementation of this approach resulted in a three-month reduction to the overall schedule as compared to a traditional approach.

JOCs and SABERs

Another tool at the disposal of federal owners is Job Order Contracting (JOC), which many practitioners consider “design-build lite.” A Job Order Contract is another long-term contract vehicle, but instead of establishing a pool of contractors for Task Order competition, it establishes contractual unit pricing through the use of a Unit Price Book (UPB) like RSMeans and a competitively-procured coefficient, which is applied to every unit price contained in the UPB.

Job Order Contracting streamlines the design and procurement process in a way that is appropriate for small projects.

Since competitive pricing is established upfront, it allows task orders to be developed on a sole source basis, often enabling a true performance-based design-build process. While JOC is not appropriate for larger projects, it can be a very effective tool for smaller projects. JOC task orders are typically under $1 million, but total contract volume can run to the hundreds of millions. The key to success on these projects is a contractor-led, simplified design process.

The JOC process typically begins with an owner-issued request for proposal detailing the project requirement, followed by a site visit where the owner and contractor develop the scope collaboratively. During this meeting, design requirements are typically defined, with much flexibility on design deliverables.

JOC contractors typically have simple design capabilities in-house, and many projects do not require anything beyond this level of definition, often called “incidental design.” Incidental design runs the gamut from contractor-produced AutoCAD to the use of annotated photos and detailed scope description to marked up as-builts. Where professional design is needed, it can often be streamlined from that required for a full bid or even a MATOC process.

It is critical that the JOC process engage design professionals when task order scope demands it, and that the JOC contract vehicle not be used as an end-run around professional design. With best practice implementation, JOC allows contractors and design professionals to offer the greatest value to their clients. Once the design is defined, whether by the contractor or a design professional, the cost can be quickly calculated using the contractual unit pricing, resulting in a lump sum task order proposal for government approval.

Opcon Inc., based in Carol Stream, Ill., holds several Job Order Contracts for the Department of Veterans Affairs throughout the Midwest. These contracts offer added value to the end-users in the demanding sphere of occupied healthcare facilities by allowing rapid and integrated development of project scopes of work, including the flexibility to hold on-site design meetings so that all parties are able to fully review existing conditions before the proposal stage in order to minimize change orders.

Effective technology support is critical when dealing with a large number of projects and unit pricing data. The largest number of JOC projects is executed by the Air Force, where the contracts go under the moniker SABER, or Simplified Acquisition of Base Engineering Requirements. The Air Force and other federal owners are further increasing the efficiency of JOC by using advanced software technologies such as project Estimator by 4Clicks Solutions and JOCWorks by RSMeans to embed JOC processes, including independent cost estimating, automatic technical evaluations, auto-population of government-mandated paperwork, and collaborative processes.

Hybrid Approaches

GSA Region 7 has long run a series of hybrid IDIQ contracts that combine the capabilities of the JOC and MATOC worlds. The contract provides great flexibility, including a unit-price structure that is often used on projects under $100,000 with the ability to compete larger delivery orders or award them on a design-build basis.

FacilityBUILD Inc., an Albuquerque, N.M.-based general contractor, holds the contract for the State of New Mexico Zone, and has completed 32 individual task orders worth nearly $2 million in the first two years of their four-year contract. The largest of these was a design-build project to convert an unused courtroom and judge’s chambers on the 11th floor of the Dennis Chavez Federal Building in Albuquerque into office space for the Small Business Administration.

Design-build team integration was evident in the closely scheduled engineering inspections which occurred midway through abatement and demolition activities, with appropriate safety precautions, so that the internal space alteration carving two floors out of the cavernous courtroom could be engineered on a fast-track schedule. The project was designed and constructed to the Executive Order 13514 for high-performance building standards, and also complied with the “GSA Green Initiative,” which requires the recycling/reuse/repurposing of a certain percentage of materials.

As the federal government faces fiscal constraints and the retirement of 50% of its acquisition personnel in the next seven years, the use of IDIQ contracts is poised to grow. The design-build community can play a proactive role in bringing the value and efficiency of our delivery method is part of the evolution of these important contract vehicles.

About the Author

Lisa Cooley is a construction industry veteran with 16 years experience in design-build and IDIQ contracting. She is a specialist in Job Order Contracting and works with RSMeans, the largest producer of construction cost data for JOC programs, to implement JOC for government owners.