Amidst the chatter about sustainability and resilience that one would expect to hear at last fall’s Greenbuild Expo in Atlanta, two related topics—Embodied Carbon (EC) and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)—almost always came up, sometimes unprompted, in conversations with exhibitors and attendees.

The Carbon Leadership Forum used that event to launch its Embodied Carbon Calculator for Construction (EC3), an open-source tool developed by Skanska and C Change Labs that allows benchmarking and assessment of embodied carbon (EC) for the purposes of design and procurement. Around the same time, Thornton Tomasetti was getting ready to make available Beacon, a parametric tool customized for structural engineers to measure EC while they are working on projects.

Greenbuild was where the construction management firm STO Building Group presented its 2019 Sustainability Survey, whose findings reveal that 48% of STO’s clients will require embodied carbon accounting on future projects. The industry’s zeitgeist also was the impetus behind the release last November of a 26-page research paper on EC in building materials for real estate, published by Urban Land Institute’s Greenprint Center for Building Performance.

All of this hubbub around EC raises the inevitable question: Why now? Why is the industry suddenly paying so much attention to embodied carbon? Are more developers and their AEC partners now committed to lowering EC in their projects, even if that means making fundamental design and specification changes?

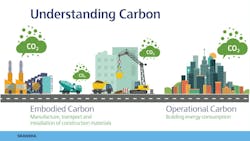

Unlike operational carbon, which can be remediated, embodied carbon can’t be removed once it’s locked into a material or building. Courtesy Skanska.

The truth is that EC has been on a lot of people’s radar screens for several years. Kate Simonen, AIA, SE, has been researching EC for at least a decade in her capacity as associate professor at the University of Washington’s Department of Architecture and as Director of the Carbon Leadership Forum (CLF). LCA tools such as Kieran Timberlake’s Tally and Athena Institute’s Impact Estimator have been approximating embodied carbon in materials and projects for a while.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology in the U.S. and the Environmental Agency in the United Kingdom developed carbon calculators. And since July 2013, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill has allowed free downloads of its Environmental Analysis Tool that can estimate EC in a project’s “early concept” to make assumptions about design, materials and building, says David Shook, PE, Associate Director and Structural Engineer in the San Francisco office of SOM.

All that being said, a number of factors have contributed to turning the industry’s interest in EC into what Amy Seif Hattan, LEED GA, Thornton Tomasetti’s Vice President of Corporate Sustainability, calls “a movement” that’s marching toward significantly reducing or even eliminating carbon from processes connected with new construction and renovation.

EC reports set off ‘alarm’

First, a little history. It wasn’t that long ago when concerns about EC seemed haphazard and random.

In a paper released in January 2017 that surveyed current industry practices, the University of Cambridge found a market where most EC measurement tools “are not transparent, up to date, open-source [or] adapted to the needs of architects and engineers.” There were uncertainties about the accuracy of the EC calculations. And the industry hadn’t even reached consensus about the length of a building’s life cycle.

EC hadn’t broken out of its second-class citizen status compared to Operational Carbon, which most developers and AEC firms were focused on reducing to improve occupant safety and comfort and to lower their buildings’ carbon footprint.

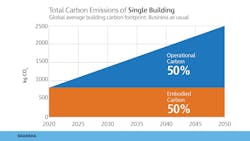

“We’ve spent the last 20 years thinking that reducing operational carbon was the [industry’s] golden ticket, but now we realize that half of the carbon that buildings emit could be embodied,” says Stacy Smedley, Skanska USA’s Director of Sustainability.

What may have altered the industry’s perception about EC were the EIA International Energy Outlook and the United Nations’ Environmental Global Status Report, both released in 2017, which estimated that EC accounted for 11% of global greenhouse gas emissions and 28% of the global building sector emissions. If the industry didn’t start making changes in the building materials it chose to use, embodied carbon would be responsible for 49% of the total emissions from new construction between 2020 and 2050. And unlike operational carbon, which can be remediated, embodied carbon can’t be removed once it’s locked into a material or building.

In other words, global carbon reduction targets spelled out in the Paris Climate Agreement—whose long-range goal is limiting increases in the global average temperature to 1.5 degrees Celsius—could only be achieved if EC is kept at bay.

The revelations about embodied carbon triggered some soul searching within the AEC community. “For the past eight years, I’ve spent every day of my professional life enabling an industry that is responsible for 40% of global climate emissions,” Stephanie Carlisle, a Principal with Kieran Timberlake, wrote for the magazine Fast Company in January. “I don’t work for an oil or gas company. I don’t work for an airline. I’m an architect. It is time for the design community to come to terms with carbon and climate change. The real challenge is design culture.”

The UN’s forecast sparked several initiatives aimed at encouraging the industry’s involvement in controlling construction’s carbon impact. These include AIA’s Architecture 2030 Challenge and CLF’s Structural Engineers 2050 Challenge. In December, the latter—whose goal is zero-carbon buildings in 30 years—was endorsed by the Structural Engineering Institute and the American Society of Civil Engineers.

The UN alarm “was a wakeup call for the industry [that] gave us only about 10-15 years to clean up our act,” says Thornton Tomasetti’s Hattan. Simonen adds that the 2050 deadline “is a timeframe that people can get their heads around.” (Thirty years is a typical life cycle for a building.)

Simonen believes that EC is now top of mind within the industry because “we know more now; there’s more data available.” Indeed, EC3 has 23,000 products in its database for nine materials categories. As of late January, it had over 3,000 registered users.

More developers engaged

It’s probably no coincidence that the industry is addressing embodied carbon at a time when governments are taking regulatory actions to rein in greenhouse gas emissions. More U.S. cities are requiring developers and property owners to provide data on the carbon impact of their buildings and, in some cases, be subject to fines if that impact rises above certain thresholds.

In January, the state of California’s Buy Clean California Act started requiring Environmental Product Declarations for certain materials like steel being specified for state building projects. USGBC–Los Angeles has been working with CLF and Sustainable Minds to develop a series of webinars and training, as well as a Buy Clean California compliance search/sort across the EPD database in the EC3 tool. Simonen says that Washington State is now considering similar legislation.

ULI Greenprint’s report states there are over 100 voluntary certifications that incorporate EC measurement. It predicts that as more U.S. cities require or incentivize green building certifications for commercial buildings, “tracking EC will become more common across the industry.”

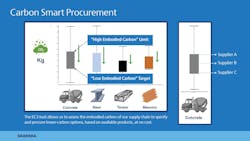

The Embodied Carbon Calculator for Construction (EC3), an open-source tool developed by Skanska and C Change Labs, has 23,000 products in its database for nine materials categories. Courtesy Skanska.

Not that developers—especially those that have made corporate carbon-reduction commitments—aren’t already engaged on this issue. Microsoft, for one, has pledged to be carbon negative by 2030, and by 2050 to remove all of the carbon the tech giant has emitted since its founding in 1975. Microsoft was the first corporate pilot for EC3, as the company set a goal of reducing embodied carbon by 15-30% in the 17 new buildings it is adding to its Redmond, Wash., headquarters.

This year, Kilroy Realty, a Los Angeles-based REIT, plans to establish upfront carbon reduction targets for its projects. “We’re very excited about the creation of the EC3 tool because what was available previously was a bit cumbersome to use,” says Sara Neff, the company’s Senior Vice President of Sustainability. In January, Kilroy got the results of its first EC3 analysis, and the company plans to use the tool on all of its projects going forward. “Now, I have a baseline, so when I set reduction targets, I know what the impact will be,” says Neff.

AEC firms take the lead

Skanska’s Smedley says that when her company first got interested in EC, the available measurement tools “weren’t providing consistent data, and you could rarely get better than averages. They weren’t transparent, and you couldn’t always understand how they got the data.”

About four years ago, Skanska, in partnership with the Charles Pankow Foundation and the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, launched a study to determine the potential embodied carbon that buildings would emit, and what could be done to reduce that amount.

Two years later, Skanska was testing the measurement tool it had developed with C Change Labs. That evolved into the calculator that CLF makes available for free as an open API.

“The industry is finally at a level of benchmarking it needs to take action,” says Smedley. “Kate and I agree that we can’t wait for perceptions; we have to act now and the make the tools better, more transparent.”

Simonen confirms that CLF worked with Tally in the pilot version of EC3. And she acknowledges that some big AEC firms such as Arup have developed parallel initiatives, “but in an appropriate way. There’s no one right answer to this problem. And while there may be some disagreements about details, there’s agreement about the fundamentals.”

Other tools out there include the Climate Emergency Tool Kit, which BuroHappold Engineering made available last September. To develop this tool, the firm consulted with AIA about how it benchmarks embodied carbon. Data from Quartz’s LCA tool is built into the engineering firm’s Buildings & Habitats object Model (BHoM) data exchange framework, says Kayleigh Houde, BuroHappold’s Computational Community Leader. The tool kit is being used primarily for measurement and design visualization, “and it doesn’t require a perfect Revit model to be effective,” says Houde.

As of January 24, Thornton Tomasetti had 160 downloads of Beacon, a Revit plug-in that is a refinement of a takeoff estimating tool called Spotlight. Robert Otani, PE, LEED AP BD+C, the firm’s Principal and Chief Technology Officer, explains that Beacon visualizes EC three ways: by materials, by building categories (such as floors, walls, foundations, and framing), and by floor levels, “so we can see where embodied carbon is hurting us the most.”

With its launch of Beacon, Thornton Tomasetti also released a seven-year study on EC, based in data from more than 600 projects that the firm gathered from structural engineers through manual measurements, and by using a “rudimentary tool” that predated Beacon. Thornton Tomasetti is currently working on an EC measurement tool that’s applicable for early stages of design.

All embodied carbon has been released by the time construction is complete. Operational carbon is emitted over time through the operation of the building, according to Skanska. The construction giant says the industry can make a bigger impact by reducing embodied carbon. Courtesy Skanska.

SOM started investigating EC in 2005, initially as an R&D exercise, and then to get the “full picture” about EC in a building’s structural frame, says Shook. What differentiates its Environmental Analysis Tool from others is that it can assess the EC that results from seismic damage and subsequent reconstruction. Shook adds that SOM has customized its tool for the construction process, which he says is relevant for companies that do business in multiple countries whose construction methods can vary widely.

SOM uses its EC tool “very actively,” and it’s been downloaded more than 1,000 times. Shook says the tool is popular with students, but hasn’t attracted as many industry practitioners as expected, possibly because it isn’t compliant with LEED v.4 (which the firm is shooting for this year). SOM plans to add exterior walls to what its tool measures for embodied carbon. “That’s important when one considers how many products and countries can be involved in that fabrication,” says Shook.

Postponing action isn’t an option

That the industry is clamoring for better data on EC is indisputable. The ULI Greenprint reports that CDP—a global disclosure system that serves investors that collectively have more than $90 trillion in assets under management—this year has started asking participants in the real estate and construction sectors how they assess EC and to provide information on CO2 emissions from new construction and major renovation.

The Canadian government is funding what Simonen calls LCA2, to build standardization into the EC measurement process. When BD+C spoke with her in January, CLF was in the process of launching an independent nonprofit entity, called Building Transparency, whose goal is to expand the Forum’s EPD database. CLF recently struck an agreement with Climate Earth, which collects data for the concrete industry, to automatically migrate concrete declarations to EC3 for digitization. “We need to automate that process” for other materials categories, says Skanska’s Smedley. “That’s our biggest challenge and opportunity.”

Building Transparency’s website concedes that EPD comparisons aren’t precise. “EC3 sorts materials by the value we are 80% confident in,” it states. Greater precision hinges on further disclosure by manufacturers.

Waiting for perfection, though, is no longer tenable, not when global emissions rose by 11% between 2010 and 2019, according to UN estimates, and when new construction is producing more than 3.7 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide annually. The EC measurement tools, at the very least, provide “a starting point to know where we are, because right now we don’t know that, either,” says Thornton Tomasetti’s Otani.

The purpose of using these tools, wrote Kieran Timberlake’s Carlisle, “is not to transform architectural design into an act of analysis. The real work now is to figure out how to make carbon assessments part of ethical and inspired design practice.”