A restroom for everyone

As designers, we spend a lot of time thinking about how people experience the spaces we design, and the best ways to optimize those experiences. In fact, we don’t just think about experience, we measure it—from how effectively people work in the offices we design, to how well they’re able to study in our libraries, or what they look for most in a trip to an outdoor mall. So when a client approached us last year and asked how they should design a gender-inclusive restroom for their workplace, we knew we had to get it right. Like anything else we do in life, using the restroom is an experience—albeit, a very private and necessary one.

It was a timely question. 2016 saw the emergence “bathroom bills” on both sides of the aisle—cities and universities across the U.S. passed gender-inclusive policies regarding restroom access, but 19 states also considered legislation last year that would override these policies and restrict a person’s access to a restroom based on their gender assigned at birth, as opposed to their gender identity. Suddenly, on both sides of the issue, there were protests over the legislation, boycotts of entire states and companies, and many more people and employers left confused, hurt, or even worse, without dignified access to a restroom. In fact, according to the National center for Transgender Equality’s 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, 59 percent of respondents in the past year had either sometimes (48 percent) or always (11 percent) avoided using a restroom, such as in public, at work, or at school, because they were afraid of confrontations or other problems. Lack of safe restroom access has been linked to medical problems such as kidney infections, urinary tract infections, and stress-related conditions.

We tackled the issue via a Gensler research grant over the past year, with a goal to document the historical, political, legislative and cultural impacts of designing gender-inclusive restrooms; and to identify best practices for inclusive restroom designs. We structured our work into three parts: 1) third-party research, 2) an internal survey of staff and 3) community roundtables. Team members included myself, Melissa McCarriagher, Stephen Swicegood, Pia Sachleben, Chad Finken, Mara Russo, Jennifer Thornton, Haley Reddick and Katy O’Neill.

Third-party Research

Our third-party research explored the history of public sanitation and its evolution through time, beginning in the Roman Empire. The first law that mandated sex-segregated toilets dates back to the late 19th century, when women began entering the workforce. It was quickly mirrored by nearly every other state. In the U.S., the women’s liberation movement and the fight for civil rights by African Americans and people with disabilities has influenced regulations on public bathrooms. We also looked at existing precedents for gender-inclusive design, academic studies, and ongoing efforts by fellow architects and designers to provide solutions.

The Survey

With a global reach of 5,500+ employees in 46 global offices, our colleagues were a prime, accessible audience for measuring experience with, or feelings about, restroom design. We received 966 responses from 35 offices across 7 countries and 5 continents. Notably, we discovered that, collectively, our colleagues had a great deal of experience working with clients on gender-inclusive design solutions, with workplace and education clients leading the way. We also learned the importance of proximity to restroom choice—if a gender inclusive restroom is located closer than a gender-segregated restroom, respondents would prefer to use it nearly 3:1. However, if they were located equal-distance from each other, 80 percent felt more comfortable using a gender-segregated restroom.

The Roundtables

We hosted four community roundtables in 2016 in Los Angeles, Chicago, Atlanta and New York, bringing together academics, business leaders, healthcare providers, human resources personnel, facilities managers, transgender people, not-for-profit executives, architects and designers. Our conversations spanned from the emotional to the pragmatic, but led to common conclusions: policy and laws alone will not solve this challenge over night; and, most likely, a singular solution will not be enough.

Another key realization during our research: while we began with transgender community’s experience specifically in mind, we quickly realized that restroom access affects everyone: transgender people, parents with children of the opposite gender, people with medical needs or disabilities, caretakers and really anyone with issues or needs around privacy. As noted in a 2015 Department of Labor & OSHA handbook, “safe access to public restrooms is a basic necessity and essential for most people’s participation in civic life, the workplace, and school.”

The Findings

- Don’t assume; accommodate. Designing for inclusivity from the beginning (instead of waiting for issues to arise) not only reinforces cultural tolerance or organizational values, but also saves money by avoiding redesigning or adding new facilities. Inclusive policies are also a driver for talent recruitment and innovation.

- Language is powerful. “Gender inclusive,” or “all gender” is preferred. “Gender neutral,” is considered problematic by the transgender community—the term erases gender identity, rather than embracing its diversity. Signage and pictograms should also be considered carefully, and within the cultural context—what works for a North American workplace may not for an international airport or highly trafficked museum.

- Design for privacy, proximity and cleanliness. Many people with disabilities and in the transgender community plan their days around using the restroom, often having to research facilities they will be able to use. But what they’re looking for is universal—privacy, proximity and cleanliness matter to everyone choosing a restroom. Features like floor-to-ceiling stalls that maximize privacy are ideal, but maintenance is also a consideration—will the cleaning equipment be able to get into the corners?

- Provide options for all users. There is no “one-size-fits-all” solution—an appropriate solution for a small workplace or restaurant will likely not work effectively for an airport or public park. Multi-user, single stall, gender-segregated options should all be considered. If providing amenities, such as sanitary napkins and disposal bins, they should be provided equally in all environments.

Common Solutions

Three commonly used design solutions emerged from the best practices we identified. These solutions are most effective when paired with an inclusive policy that allows people to use the facility consistent with their gender identity. The policy should also address gender non-binary people; typically, they should be allowed to use the facility they feel safest in.

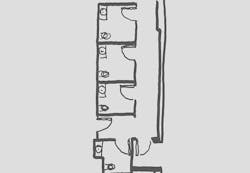

Single-user solutions offer privacy for all users, and are most appropriate for small work environments, or low-traffic areas. Signage should be designated gender-inclusive (pending local code requirements), and visual locks displaying “occupied” vs. “vacant” offer further privacy. The downside: if these are the only option, they can be costly to implement for large populations.

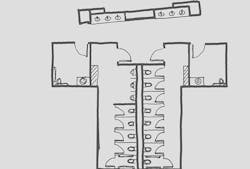

Hybrid solutions combine private and communal spaces for all users, and are most appropriate for work environments, public places and high-trafficked areas. They are often accompanied by policy indicating individuals may use spaces consistent with their gender identity, and the provision of some single-user spaces also supports the needs of families and those needing additional assistance, or people who prefer more privacy. Communal sinks can complement an inclusive policy while allowing for shared plumbing and cost savings.

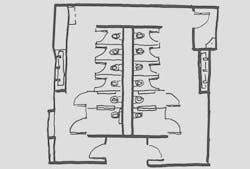

Multi-stall solutions provide privacy for all users, and are most appropriate for high-trafficked, well-secured public spaces—particularly when offered in addition to single-occupancy and/or gender-segregated spaces in close proximity. Signage and policy must be clearly communicated (preferably multilingual), and code requirements should be thoroughly reviewed by local architect. Floor-to-ceiling stalls may also require additional lighting, ventilation or structural support; considerations for security should also be analyzed.

Next Steps

Access to bathrooms based on gender identity continues to be engrained in controversy, leaving near-term solutions often in the hands of building owners and tenants looking to provide the best solutions for their employees and visitors. Fifteen states have restrictive legislation on their dockets in the coming year, and North Carolina’s HB2 law, which mandates individuals may only use restrooms and changing facilities that correspond to the sex on their birth certificates, remains in place, despite being widely unpopular, with only 32 percent of voters in the state supporting it.

Code requirements show progress towards inclusion. The 2018 International Building and Plumbing Codes now includes code provisions for “gender-neutral” restrooms as proposed by the AIA (403.1.2; IBC 2902.1.2). According to the AIA, “States and local jurisdictions can adopt the 2018 IBC (when it is published by the International Code Council in spring 2017) or they can adopt the new code provision if they are currently updating their state or local building codes. Doing so would expedite the review and permitting process for this type of bathroom design.”

Because of the diverse landscape of laws and policies, and the unlimited configurations possible based on users and building type, it’s nearly impossible to offer one prescriptive solution that would benefit all users and building owners, while also being compliant with local laws and ordinances. But, with careful consideration, we can continue to move the needle in the right direction to provide better experiences for all.

As senior communications strategist in Los Angeles, Nick Bryan helps Gensler practitioners connect with their clients and communities through the power of creative content. He has more than 15 years experience working with architects and engineers to tell their stories.