In order to better understand the Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) Model, let’s take a metaphorical trip to a doctor’s office.

Imagine we are having a wound treated, a wound that was caused by diabetes. During our visit, we are seen by an endocrinologist to help us better manage our diabetes. We are then seen by a Nutritionist to help manage and plan our meals based on our health needs. Lastly, before leaving, a pharmacist stops by to provide medications on the spot.

Some of you may be wondering, “What does this have to do with IPD?” Well, in the above example, this type of cross-discipline, co-location, and utilization of expertise, or “integrated care team,” as some call it, is part of a recent paradigm shift that the healthcare industry is feeling nationwide.

This shift can be viewed as analogous to the IPD model. While IPD is deemed transformational and revolutionary based on its ability to mine risk through financial incentive, contracted in an Integrated Form of Agreement or Tri-Party Agreement (an agreement between the owner, architect, and contractor), it is how the three parties collaboratively work together. The underlying variables and tools used to manage collaboration between teams is ultimately the driving for success with IPD.

DAY-TO-DAY TOOLS FOR IPD

To ensure goals are met, it is imperative that teams identify and utilize an effective structure to hold every member accountable to a near-term degree. In project delivery, there are usually three main, big-picture goals that all team members are aiming to achieve: scope, schedule, and budget. What sets the IPD delivery model apart from others are the tools and structure implemented by the IPD team to deliver the project within or under budget while still meeting the owner’s needs.

To maintain accountability for a big-picture item, there must be a means by which teams can track their progress. If this is not done properly, it can lead to major issues ranging from budget overages to change orders to schedule slips. Ever heard the adage “out of sight, out of mind”? Well, to avoid falling into this pattern, many IPD teams engage in daily stand-up meetings. These meetings are brief, 10-20 minutes, where all three parties stand and review a list of items that require some type of action within the next week. This may seem short and redundant at first, but once team members own an action, the benefit of these meetings becomes very clear.

Through the natural and innate human desire to succeed, these meetings drive every member of the team to be accountable, urgent, and collaborative with all three entities of the IPD agreement throughout all phases of the project.

IPD allows these meetings to drive the big-picture goals because the architect, contractor, and owner are able to discuss construction and design items every day, through the design, preconstruction, and construction phases and all the way through closeout.

Target Value Design (TVD) is a major tool in setting IPD apart from traditional methods. TVD breaks the mold of contractors providing estimates based on detailed design. Instead, estimates are based on a target cost which is collaboratively established amongst all team members.

TVD in IPD diminishes the traditional “throw-it-over-the-wall” design since contractors and sub-contractors are brought on board in the design phase. This allows the designers to engage the people who will be procuring and finishing-out their projects as they design. This helps avoid design results that require re-work due to constructability and budget issues, de-value engineering and delay.

Stemming from TVD, an IPD team participates in PITs, or Project Implementation Team meetings, also known as Component Team Meetings. PIT meetings are comprised of interdisciplinary groups of project participants, and are crucial in achieving success with IPD.

Typically with IPD, there are PIT teams for each major aspect driving the design and construction: MEP PIT, Civil/Site PIT, Structure PIT, Build/Fit-Out PIT, Equipment PIT, Food Service PIT, AV/IT PIT, Closeout PIT, etc. (there can be more groupings depending on the size of the project). These meetings are extremely successful and serve as the foundation of TVD. It is in these meetings that designers are able to engage and receive real-time feedback from the subcontractors and other team members who will be executing the design in the field.

Also, like the stand-up meetings, the PIT meetings take place through all phases of the project, ensuring the designers are receiving real-time answers from subcontractors and vendors before construction has begun and often before final documents are issued.

RESULTS

So let’s imagine a construction project that brought all major players on-board almost concurrently. With an owner’s vision, or preliminary program, the architect, contractor, and owner may all work together to establish the target-value with detailed estimates to drive expectations.

The detailed estimate design originates in an environment that has harnessed and co-located all key players, of not only the design phase, but also the construction phase. Below is an example of how this type of environment and structure enhances project goals when utilizing IPD.

At a weekly MEP PIT meeting, the owner-representative informs the team that the owner has decided to change the original HVAC selection from a chilled water to a DX central AC plant. The mechanical contractor, present in the meeting, is able to get specifications for the DX system. The engineer and architect, also in attendance, are able to begin redesign work and plan changes. The contractor is able to revise pricing based on the new system selection and all other related aspects that will change.

All of the rework and revisions are completed in less than a week and within budget. The schedule is not impacted and the plans are changed prior to pouring the slab. The team is thus able to collaborate and provide the owner an estimate of the affect the changes will have on important operational parameters such as heat/cool loads, maintenance, and facility operations cost, post-occupancy.

Because of the nature and processes inherent in IPD, this issue did not impact the schedule or budget. The issue was brought up before construction had begun, the subcontractor was able to provide the designer and engineer with all necessary information and support to ensure constructability was guaranteed, and the design team was able to make the plan change prior to the release of final plans. What could have been a very pricey and time-consuming Change Order was mitigated through a collaborative re-planning session in which all valuable project team members participated.

CONCLUSION

The IPD method incentivizes all team members to work collaboratively to provide the client with the best possible product; a project that meets scope, maintains budget, and delivers on schedule.

Like the Integrated Care Teams mentioned previously, an IPD team is a one-stop shop that is established during or even before design. This delivery method cultivates cross-discipline design, ideally before construction begins, through various tools that help to focus accountability on not just an individual level, but also a team-wide level.

Both figuratively and literally, IPD provides a design and construction world without walls and fences. It instead provides a clear definition and structure of the near-term and long-term goals of the entire project team at large. Ambiguity is a major enemy of IPD, but utilization of the proper tools creates transparency in every aspect of design, budget, schedule, and construction.

The project vision will be as clear to the owner as it is to the designers, contractors, and down through the entire project team.

About the Author

Megan Donham is an Associate Consultant with CBRE Healthcare. She can be reached at megan.donham@cbre.com.

Related Stories

| Dec 2, 2014

Nashville planning retail district made from 21 shipping containers

OneC1TY, a healthcare- and technology-focused community under construction on 18.7 acres near Nashville, Tenn., will include a mini retail district made from 21 shipping containers, the first time in this market containers have been repurposed for such use.

| Dec 2, 2014

Main attractions: New list tallies up the Top 10 museums completed this year

The list includes both additions to existing structures and entirely new buildings, from Frank Gehry's Foundation Louis Vuitton in Paris to Shigeru Ban's Aspen (Colo.) Art Museum.

| Dec 2, 2014

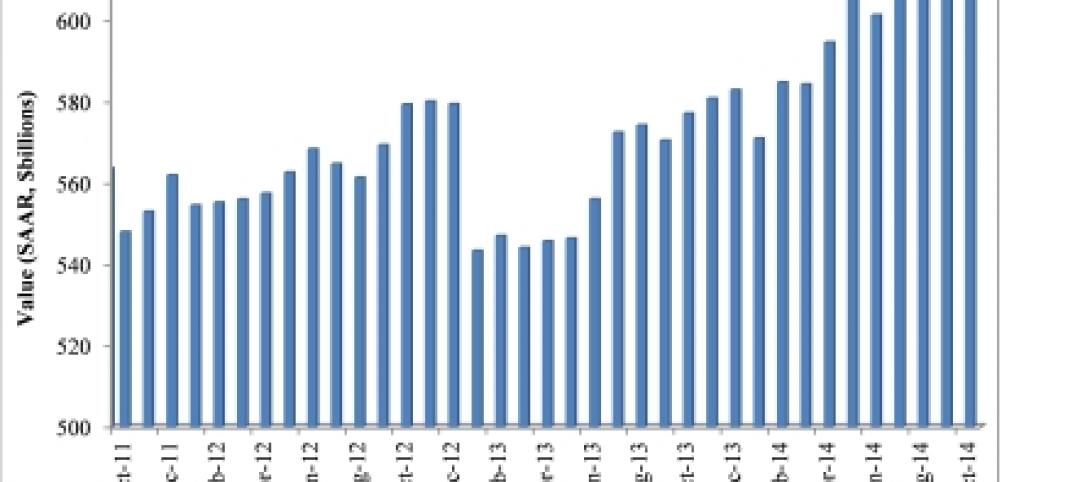

Nonresidential construction spending rebounds in October

This month's increase in nonresidential construction spending is far more consistent with the anecdotal information floating around the industry, says ABC's Chief Economist Anirban Basu.

| Dec 2, 2014

Hoffmann Architects announces promotions

The architecture and engineering firm specializing in the rehabilitation of building exteriors announces the promotion of members of its Connecticut staff.

| Dec 2, 2014

SPARK designs urban farming housing for Singapore’s elderly population

The proposal blends affordable retirement housing with urban farming by integrating vertical aquaponic farming and rooftop soil planting into multi-unit housing for seniors.

| Dec 2, 2014

Bjarke Ingels unveils cave-like plan for public square in Battersea Power Station

A Malaysian development consortium is guiding the project, which is meant to mimic the caves of Gunung Mulu National Park in Sarawak, East Malaysia.

| Dec 1, 2014

9 most controversial buildings ever: ArchDaily report

Inexplicable designs. Questionable functionality. Absurd budgeting. Just plain inappropriate. These are some of the characteristics that distinguish projects that ArchDaily has identified as most controversial in the annals of architecture and construction.

| Dec 1, 2014

Skanska, Foster + Partners team up on development of first commercial 3D concrete printing robot

Skanska will participate in an 18-month program with a consortium of partners to develop a robot capable of printing complex structural components with concrete.

| Dec 1, 2014

How public-private partnerships can help with public building projects

Minimizing lifecycle costs and transferring risk to the private sector are among the benefits to applying the P3 project delivery model on public building projects, according to experts from Skanska USA.

High-rise Construction | Dec 1, 2014

ThyssenKrupp develops world’s first rope-free elevator system

ThyssenKrupp's latest offering, named MULTI, will allow several cabins in the same shaft to move vertically and horizontally.