Empty churches and shuttered parochial schools are scattered throughout neighborhoods in many older U.S. cities, and Chicago is no exception. Meanwhile, many daycare providers, community organizations, and charter schools are desperate for program space. Could this be evidence of divine providence at work?

The story of Concordia Place illuminates both the difficulties and rewards of trying to match empty buildings with social programs. Concordia Lutheran Church, founded by Swedish Lutherans in 1898 and today a member congregation of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, was seeking to expand its highly successful early childhood program, Concordia Place. That program was started in the early 1980s, when three single mothers pleaded with the small, 60-member congregation to provide low-cost childcare.

Located in Chicago’s North Center neighborhood, about six miles northwest of the Loop, Concordia Place had a long waiting list and no space in which to grow. When a shuttered Catholic church, St. Veronica’s, about a mile southwest of Concordia, came on the market, Concordia’s leaders sprung at the opportunity.

Project summary

CONCORDIA PLACE

Chicago, Ill.Building Team

Owner: Concordia Lutheran Church

Owner’s representative: Cotter Consulting

Project planning and development: LL Consulting

Architect, interior design, SE: Holabird & Root

MEP engineer: EME (now KJWW)

Civil engineer: Terra Engineering

Historic preservation consultant: Harboe Architects

Landscape architect: McKay Landscape Architects

Contractor: Bulley & AndrewsGeneral Information

Project size: 28,000 sf

Construction cost: $5.6 million

Delivery method: Design-bid-build

There was talk about razing the structures in order to build condominiums, but the local community would hear nothing of that: They wanted the buildings preserved and repurposed to serve mounting social demands. Concordia members undertook a multi-year fundraising campaign, doubling their regular contributions, mortgaging existing church facilities, and soliciting donations from businesses, foundations, and government sources

Unravelling a hodgepodge of building uses

The property featured an unusual set of structures. St. Veronica Parish was founded in 1904 and a year later dedicated a combination church-school building. What looked like a three-story brick-and-limestone school actually contained a sanctuary on the ground floor, classrooms on the floor above, and a large community hall on the third. Gone was an old convent in a wood-frame penthouse above it all; it was destroyed by fire years ago.

In contrast to the modest church-school structure, the rectory, built a decade later, was an imposing red brick Tudor design by noted ecclesiastical architect Henry Schlacks. The archdiocese closed both church and school and sold the property to the city of Chicago in 1989. For a time, it was used as overflow space for a nearby public school, but within a few years it was vacant and subject to repeated vandalism.

Such combination church-school buildings may be the most readily adaptable of church properties, as they usually have no bell towers, large rose windows, or tall, voluminous naves. The lack of the typical church basement meant that the main level was just up from the sidewalk, making ADA compliance easier to achieve.

When Concordia Lutheran eventually purchased the property, the first two floors of the church-school building prooved perfect for their early childhood and preschool program. But according to the church’s pastor, Reverend Nicholas J. Zook, the leaders wondered what to do with the cavernous third floor. They surveyed the community and found that, due to heightened gang activity in the neighborhood, teen programs would be welcomed. There was also a large population of seniors and non-English-speaking adults with unmet needs.

Thus, it was envisioned that the so-called “bonus space” of the third floor could house a community center that would offer after-school and summer camp programs for ages six to 12, leadership development for teens, English classes for adults, and wellness programs for seniors.

Keeping program needs and preservation in mind

Local architects Holabird & Root were charged with meeting the varied programmatic needs of these diverse user groups while preserving the historic exteriors. Careful site planning made use of virtually every square inch of the property. “We wanted to get as much space as possible for the kids to play in, but we also wanted to make a welcoming gesture to the public,” says Maria Segal, RA, then Holabird & Root’s early childhood design specialist. (She is now with Blender Architecture, Chicago.)

General contractor Bulley & Andrews demolished a decrepit 1950s addition and replaced it with a single-story annex. Its colors and materials—soft red and light sage green composite cement panels—mediate between the red brick rectory and the yellow brick church-school building. Siting the annex at the back of the lot created a courtyard that is now used for both school and community events, including a farmers’ market run by the after-school teens.

The high-ceilinged annex is used for children’s large-motor activities as well as banquets, community meetings, and worship services. Extensive glazing provides a visual connection to the outdoors and makes it glow during evening events. A playground for the preschool children is just south of the annex, and a fenced play area for toddlers is tucked into the north part of the site, offering direct access from those classrooms.

Because the church complex was rated orange on the Chicago Historic Resources Survey, the project was able to obtain state funds. That triggered the involvement of the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, which directed Concordia to preserve all existing window openings. This was at odds with Concordia’s desire to change some of the windows into glass-paned doors for the first floor classrooms.

The IHPA and Concordia reached a compromise: alternating windows were changed into doors, and small square windows were punched into the walls below the sills of the remaining windows. The original wood windows were restored and double-glazed.

Except for a stairway in the southeast corner, the interior of the church-school was gutted. Folding wooden doors that divided a large room on the third floor were reused for the same purpose.

The archdiocese had removed about half of the stained glass windows before selling the property. Those that remained were removed from the first-floor sanctuary and placed in backlit frames in the historic stairwell and in the third-floor teen room, which can also serve as a chapel. The IHPA did not require the stained glass to be preserved, but Reverend Zook insisted that it be done anyway, as a gesture “to show continuity with this place as an anchor in the community.”

The interior materials palette is in neutral, soothing colors with natural materials, such as birch plywood, used wherever possible. “That way the child brings the life and color to the spaces,” Segal says.

Reverend Zook praises the 28,000-sf, $5.6 million project, for its maximization of natural light and for providing and an abundance of storage areas from otherwise useless space, which helps maximize the flexibility of the rooms.

Keeping the scale right

A child-appropriate scale was also achieved despite the high ceilings by breaking down the scale of the classrooms with alcoves, cubbies, and lofts. Activity areas are defined by changes in ceiling and floor treatments. Low, square windows provide views into adjacent classrooms as well as to the outdoors. During construction, a number of cast-iron columns were discovered; these columns had to be reinforced with a secondary set of steel supports.

The third floor has an array of spaces whose flexibility has contributed significantly to the building’s success as a community center. Reverend Zook dreamed of a grand lobby on the first floor, but that space was needed for classrooms. Instead, the project team created a great lobby upstairs, where a pitched-roof skylight structure provides abundant north light, and a café serves as a multipurpose space used throughout the day by seniors, adults, and teens. New doors can close off the corridor to separate the licensed preschool spaces from the community areas

This kind of mixed-use facility is a model for the pooling of community resources that is now often necessitated by tight budgets, especially for nonprofit entities like Concordia.

Two campuses, one mission

Renovating the buildings and constructing the annex resulted in a dramatic expansion of Concordia’s mission and program. Concordia Place’s two campuses now serve a multi-age population from babies to senior citizens, providing more than 300 children (95% of whom are not Lutheran) with childcare and after-school programs. Seventy percent of the children in the new program come from minority families, nearly half of which are headed by single parents.

Reverend Zook feels that the marginal added costs of preservation were a demonstration of Concordia’s “good-faith relationship to the community.” Instead of being lost to the wrecking ball, this former church serves a new organization’s mission as a place where, in the minister’s words, “The church’s witness of outreach is grounded in her service to the larger community of neighbors in which she lives.” +

--

Laurie Petersen is a regular contributor to Chicago Architect, the official publication of AIA Chicago, from which this article was adapted.

Related Stories

University Buildings | Jun 18, 2024

UC Riverside’s new School of Medicine building supports team-based learning, showcases passive design strategies

The University of California, Riverside, School of Medicine has opened the 94,576-sf, five-floor Education Building II (EDII). Created by the design-build team of CO Architects and Hensel Phelps, the medical school’s new home supports team-based student learning, offers social spaces, and provides departmental offices for faculty and staff.

Healthcare Facilities | Jun 18, 2024

A healthcare simulation technology consultant can save time, money, and headaches

As the demand for skilled healthcare professionals continues to rise, healthcare simulation is playing an increasingly vital role in the skill development, compliance, and continuing education of the clinical workforce.

Mass Timber | Jun 17, 2024

British Columbia hospital features mass timber community hall

The Cowichan District Hospital Replacement Project in Duncan, British Columbia, features an expansive community hall featuring mass timber construction. The hall, designed to promote social interaction and connection to give patients, families, and staff a warm and welcoming environment, connects a Diagnostic and Treatment (“D&T”) Block and Inpatient Tower.

Concrete Technology | Jun 17, 2024

MIT researchers are working on a way to use concrete as an electric battery

Researchers at MIT have developed a concrete mixture that can store electrical energy. The researchers say the mixture of water, cement, and carbon black could be used for building foundations and street paving.

Codes and Standards | Jun 17, 2024

Federal government releases national definition of a zero emissions building

The U.S. Department of Energy has released a new national definition of a zero emissions building. The definition is intended to provide industry guidance to support new and existing commercial and residential buildings to move towards zero emissions across the entire building sector, DOE says.

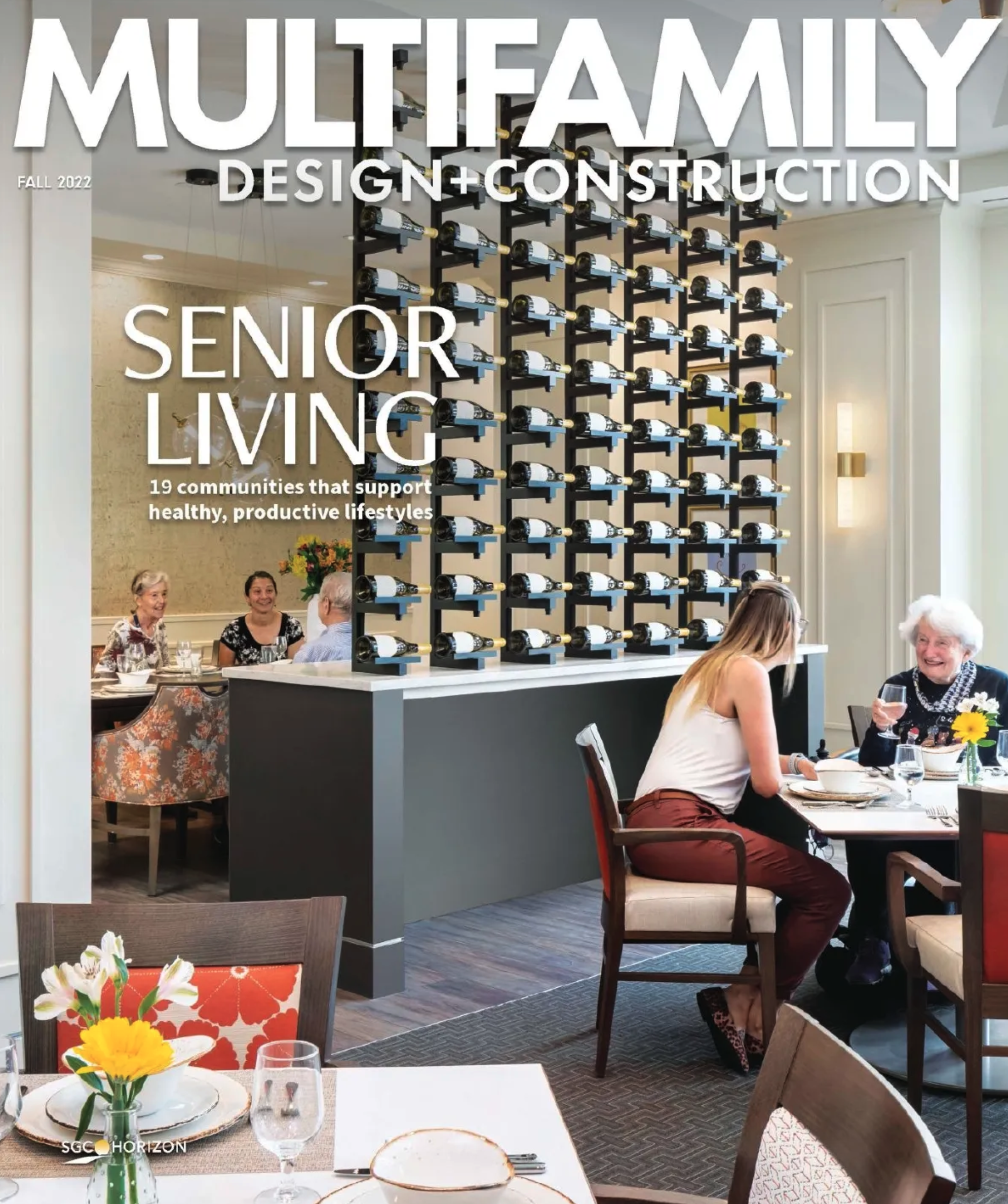

Multifamily Housing | Jun 14, 2024

AEC inspections are the key to financially viable office to residential adaptive reuse projects

About a year ago our industry was abuzz with an idea that seemed like a one-shot miracle cure for both the shockingly high rate of office vacancies and the worsening housing shortage. The seemingly simple idea of converting empty office buildings to multifamily residential seemed like an easy and elegant solution. However, in the intervening months we’ve seen only a handful of these conversions, despite near universal enthusiasm for the concept.

Healthcare Facilities | Jun 13, 2024

Top 10 trends in the hospital facilities market

BD+C evaluated more than a dozen of the nation's most prominent hospital construction projects to identify trends that are driving hospital design and construction in the $67 billion healthcare sector. Here’s what we found.

Adaptive Reuse | Jun 13, 2024

4 ways to transform old buildings into modern assets

As cities grow, their office inventories remain largely stagnant. Yet despite changes to the market—including the impact of hybrid work—opportunities still exist. Enter: “Midlife Metamorphosis.”

Affordable Housing | Jun 12, 2024

Studio Libeskind designs 190 affordable housing apartments for seniors

In Brooklyn, New York, the recently opened Atrium at Sumner offers 132,418 sf of affordable housing for seniors. The $132 million project includes 190 apartments—132 of them available to senior households earning below or at 50% of the area median income and 57 units available to formerly homeless seniors.

Mass Timber | Jun 10, 2024

5 hidden benefits of mass timber design

Mass timber is a materials and design approach that holds immense potential to transform the future of the commercial building industry, as well as our environment.