Student housing is as important a selling point on American campuses today as the number of spin bikes in the rec center. Administrators at the nation’s 3,011 four-year institutions know that if their residential offerings aren’t absolutely top of the line, the best students will—with their parents’ blessing—look elsewhere for their degrees.

But new student residences can also help solve problems unique to their respective institutions. Let’s look at three such examples—at Arizona State University, Middlebury College, and the University of California, Irvine.

ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Advancing ‘The Fulton Difference’

Growing pains. That’s what Arizona State University’s engineering program was going through. “We doubled in size in the last six years,” said Kyle D. Squires, PhD, FAPS, Dean of ASU’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering. “FSE,” as it is known, had exploded to 21,000 students, making it the largest engineering program in the country—which was exactly what the university had planned for.

That rapid trajectory did, however, put intense pressure on the university to house all those aspiring engineers. At the main campus in Tempe, FSE students were scattered over a number of residence halls, a situation that ran counter to the university’s goal of housing students—especially first-year Sun Devils—in single-discipline “residential colleges.”

“We stress what we call ‘The Fulton Difference,’” said Squires. “It’s a culture that students can build on for their entire lives as engineers.” A new residential college devoted exclusively to FSE engineers would strengthen that experience.

Thanks to ongoing donations from ASU alums Gary L. Tooker, former chairman of Motorola, and his wife, Diane, that aspiration has been realized in the Fulton Schools Residential Community at Tooker House. The 458,000-sf complex serves 1,594 mostly first-year FSE students. (Upper-division students get the first two floors.)

The $120 million project was completed as a public-private partnership between ASU and American Campus Communities. Since 2006, ACC has provided Arizona State with residences totaling more than 7,719 beds (including Tooker House).

See Also: Bicycle kitchens give cyclists their very own amenity space

WRESTLING WITH A HARSH DESERT CLIME

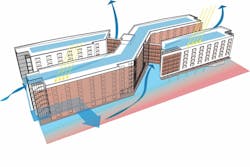

The seven-story complex was designed to mitigate Tempe’s desert climate, where the temperature routinely exceeds 100. According to Jim Curtin AIA, Principal, Solomon Cordwell Buenz, the design firm conducted extensive shading and wind modeling to determine the optimal shape and orientation for the building.

From those studies emerged a solution that called for two parallel building masses facing east-west and shaped in a figure eight. This “infinity” configuration shades the interior courtyard formed between the masses and ushers in cooling winds from the west.

The shaded “canyon” leads out onto an extensive public lawn; it can also be accessed from the 525-seat dining hub. This fluidity has turned the area into a popular social/event venue at ASU. “Last fall, the homecoming committee specifically asked to have a function there,” said Squires. “It’s become a big draw on the campus.”

On the west section of the south façade, SCB specified vertical louvers set four feet from the wall to shade the building. “Using Grasshopper and other software, we were able to determine the exact position for each louver to curtail heat gain,” said Curtin.

On the south façade’s eastern half, inverted U-shaped visors were installed over and around the high-performance glazing. The buildings were clad in insulated metal panels, stone, and EIFS, yielding an effective R-23 rating for the walls. “For this desert environment, the more we could insulate the exterior the better,” said Curtin. Mechanical systems and other behind-the-wall sustainable features were exposed so that the students could learn from them. Tooker House earned LEED Gold certification.

PUTTING THE EMPHASIS ON COLLABORATION

What makes Tooker House special is how it encourages interaction among students, starting with the living spaces. There are some private rooms, but most are fully furnished quads: two double-occupancy rooms with a shared bath. Because Tooker House residents come from a variety engineering disciplines—computer science, informatics, transport, electrical, sustainability, etc.—the possibility of serendipitous learning opportunities looms everywhere. “It’s good for students to hear from others who are outside their major,” said Squires.

The big buzz is the ground-floor maker lab, a 3,500-sf open space equipped with 3D printers, laser cutters, soldering tools, wall-to-wall whiteboards, adjustable tables, and lockers for storing projects. Sliding glass Nanawalls open onto a courtyard, where students can display their work on exhibit pedestals.

Adjacent to the maker lab is an e-space classroom where first-year students take their “FSE 101, Introduction to Engineering” course. “It’s all designed to encourage collaboration,” said Jennifer Hightower, Vice President of Student Services. “We wanted a space that would lead to interdisciplinary conversations.”

Dean Squires makes no bones about the university’s grand strategy for its gargantuan engineering program—and how Tooker House fits into it. “We want to have a catalyzing effect on the metro Phoenix valley,” he said. “We just graduated four thousand engineers. Two-thirds will stay in Arizona, many of them in metro Phoenix. We want to produce the engineering talent for companies like Intel and Medtronic, which are already here, and help attract new employers,” such as Benchmark Technologies, which last fall announced it was moving its headquarters to Tempe.

To the extent that Tooker House provides the kind of environment that attracts and develops top engineering students, it is playing its part in furthering the Fulton Difference.

PROJECT TEAM | FULTON SCHOOLS RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITY AT TOOKER HOUSE

CLIENT Arizona State University DEVELOPER American Campus Communities ARCHITECT Solomon Cordwell Buenz SE PK Associates CE HDR MEP/FP GLHN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT Trueform GC Okland Construction

Middlebury College: How to keep students on Campus?

Founded in 1800, Middlebury, a liberal arts college of 2,500 undergraduates, is nestled on 350 acres in Vermont’s Champlain Valley. Views of the Green Mountains and the Adirondacks make it one of the most idyllic campuses in New England, if not in the whole country.

A few years ago, Middlebury officials determined that too many students—120, to be exact—were living off campus. “That was more than we wanted off campus,” said Douglas Adams, until recently Associate Dean of Students for Residential and Student Life. The college wanted to slice that number in half.

Adams knew that simply building more housing—especially traditional “dorms,” where most Middlebury students lived—was not the answer. The new housing would have to compete head-to-head with the allure of off-campus living. Compounding the problem: the imminent loss of outmoded modular units housing 35 students.

RURAL VERMONT MEETS THE NEW URBANISM

Middlebury had always financed its own construction, but not this time. “The college was not in a position to extend the capital cost of building new student beds. It had other priorities,” said Tom McGinn, Middlebury’s Project Manager in Planning, Design & Construction. For the first time, Middlebury contracted a private entity, Kirchhoff Campus Properties, as developer. In turn, Kirchhoff brought in one of its preferred designers, Union Studio Architecture & Community Design.

Union Studio, a Providence, R.I., firm deeply rooted in the New Urbanism, had done some work for Kirchoff in the past. “They appreciated our ethos—to create places that had an identity, as well as being contextual,” said Douglas Kallfelz, AIA, LEED AP, CNU, Managing Partner.

Identity. Context. Those were the watchwords that shaped the project. After extensive meetings with college officials, notably the Board of Trustees’ Building and Grounds Committee (“a very engaged group,” said McGinn, with a chuckle), a sloping site near a residential neighborhood on the edge of campus was chosen.

Here, Union Studio positioned three townhouse structures in a U around a west-facing greenspace that affords a stunning view of the Adirondacks. The 2,700-sf townhomes—a first for Middlebury—have two bedrooms on the lower level, two on the main floor, and four up top. Each has three full baths, a kitchen, living space, and a laundry. Twelve such configurations, totaling 96 beds, are spread over the three structures.

A separate apartment building, Ridgeline Residence Hall, has 62 bedrooms clustered in 1,000-sf suites, each with 3-4 singles and shared bath, kitchen, and laundry. Suites are arranged around large common rooms. An upper-floor great room looks out over the valley.

Kallfelz said the design vocabulary of the new residences derived from three influences: the agrarian character of the Champlain Valley, the residential aspect of the nearby homes, and the more formal scale and feel of the nearby campus. The steeply pitched roofs, rustic wood braces, and white cementitious clapboard siding perfectly reflect the stately, rural nature of the surrounding countryside. “We worked very hard to keep that vernacular,” said Adams.

All 158 rooms have full-size single beds and storage for skis and boots. (Middlebury has its own Snow Bowl 13 miles from campus.) Curiously, the closets have no doors. “In our other residences, the students were asking us to take the doors off because they took up too much room,” said McGinn. Instead, the closets have a rod to hang a curtain on. “Makes for a lot less maintenance,” he said.

McGinn, a 20-year veteran at Middlebury, praised Kirchhoff and Union Studio for being receptive to the college’s priorities. “We always spend time with the developer and the designers to make sure we know what we’re getting,” he said. Details like floor finishes (VCT preferred), furniture quality (“it’s got to be durable”), even trash collection and recycling, have to be worked out early.

“Make sure everything fits with your campus standards,” he said. “We use certain suppliers for our projects, and I don’t want to have a separate stockroom for some other manufacturer’s stuff.”

In the two years since their completion, the new residences—especially the townhomes—have become the most popular housing on campus, said Adams. The newness helps, of course, but he also credits the strong community identity created by the greenspace common, numerous shared areas, and communal kitchens.

And that “off-campus” situation? It’s down to 60. Exactly as planned.

PROJECT TEAM | RIDGELINE RESIDENCE COMPLEX

CLIENT Middlebury College DEVELOPER Kirchhoff Campus Properties

ARCHITECT, INTERIOR DESIGN Union Studio Architecture & Community Design SE Camera / O’Neill Consulting Engineers SITE SE Richard M. Doherty, PE CIVIL ENGINEER Otter Creek Engineering SITE EE Engineering Services of Vermont MEP/FP Collective Design Associates LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT Wagner Hodgson Landscape Architecture GC Naylor & Breen Builders

UC Irvine: Pumping up the density

For 50 years, since its founding in 1965, the University of California, Irvine, stuck to a two-story, low-density campus housing paradigm appropriate to its suburban Orange County location. On January 20, 2016, that model was disrupted by an announcement from Janet Napolitano, President of the UC system, directing the 10 UC campuses to build a total of 14,000 new student housing units by 2020.

“We knew we needed to provide more housing, more beds, and to do it more densely,” said Brian Pratt, AIA, DBIA, LEED AP, UCI’s Assistant Vice Chancellor/Campus Architect. Not to mention more affordably, given the limited supply of affordable rentals in UCI’s metro area.

Luckily, UCI was able to respond almost immediately to Napolitano’s directive with a project it had in the pipeline: its first high-rise residence, Mesa Court Towers, three six-story structures totaling 250,972 sf. Completed in fall 2016, the $96.7 million complex provides beds for more than a thousand first-year students, in 269 rooms. There’s a 19,975-sf, 950-seat dining commons (“The Anteatery,” after UCI’s mascot, the anteater) that can serve up to 2,500 students, a 2,906-sf fitness center, a very popular café, music and billiards rooms, a yoga center, and nine each of communal kitchens, great rooms, and laundry rooms. All this on 2.75 acres. Hello, high density!

DESIGN-BUILD COMES TO THE FORE

UCI’s Pratt attributed much of the success of the Mesa Court project to the design-build team, led by architecture firm Mithun and design-builder Hensel Phelps. “We’re huge proponents of design-build,” said Pratt. “We’ve been doing it for 25 years.” He said he likes the “cost certainty” that comes with holding a design-build competition (“we know how much we have to spend”) and the speed of delivery (“much faster than what most of our peer institutions can deliver”). Mesa Court was completed in 28 months, from contract award to occupancy.

What he likes most about design-build, said Pratt, is the innovation that it inspires. “We’re religious about the selection process being blind,” he said. “We score our competitions on best value, not price, and we get the top teams in the country—great, fabulous designs! We want to see teams taking some risks because we know that nine times out of ten we will be the beneficiary.”

Mesa Court took advantage of one such unanticipated innovation. Mithun laid out the floors to UCI’s standard “suburban” model, three beds to a room. But this time the architecture firm designed the rooms with 10-foot ceiling heights, while still meeting the budget constraints. As a result, UCI was able to comfortably furnish about 150 of the rooms as quads with two sets of bunk beds each—a 33% gain in occupancy per room.

“We expected students to push back, but they love the loft feeling,” said Pratt. Bill LaPatra, AIA, LEED AP, the Mithun Partner on the job, said, “There were zero complaints. The parents were happy because they got a deal on the price.” By the second year of operation, the university had shifted Mesa Court almost entirely to quads.

The design-build team also surpassed UCI’s sustainability standard (LEED Gold), achieving LEED Platinum certification. At the start of the project, the UC system required new construction to best California’s Title 24 energy-conservation standard by 20%. “Title 24 got more restrictive in the middle of the project,” said Pratt. “Still, the team more than met that goal,” beating Title 24’s energy requirements by 30%.

A thermal mass of up to 30 inches of concrete provides seismic performance and helps modulate interior temperature. High-performance operable windows allow three-fourths of the building space to be cooled by natural ventilation. The buildings use solar hot-water systems and electricity-generating photovoltaics,

In 2017, the Design-Build Institute of American named Mesa Court Towers its Project of the Year.

UCI is forging ahead to fulfill its share of the UC system’s 2020 target. Next up: UCI’s 215,000-sf “Middle Earth Expansion”—two five-story towers that will house 494 first-year students, along with a dining facility capable of serving 7,300 meals a day.

The design-build team for the new job: Mithun and Hensel Phelps.

PROJECT TEAM | MESA COURT TOWERS

CLIENT/OWNER University of California, Irvine ARCHITECT/LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT Mithun, Inc. SE DCCL Engineers CE KHR Associates MECHANICAL ENGINEER Hartford Engineering ELECTRICAL ENGINEER Michael Wall Engineering ACOUSTICAL Veneklasen Associates COMMISSIONING Zaretsky Engineering GC Hensel Phelps