Six finalists selected in design competition for Canadian Holocaust monument

By BD+C Staff

The Department of Canadian Heritage is currently holding a design competition for the new National Holocaust Monument, and it is narrowed down to six finalists. The six entries were displayed to the public on February 20 and viewers were allowed to comment on the designs.

A seven-member jury will recommend the winning design to the government of Canada after taking the public’s comments into account.

The competition began in May 2013, when the department asked for competitors to submit their credentials and examples of prior work. Six teams were chosen to move forward and actually develop concepts.

The monument itself, whatever form it takes, will face the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. It is scheduled for inauguration in fall 2015.

Take a look at the proposed designs, with descriptions from their creators:

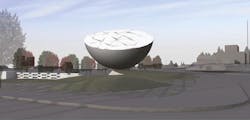

Team Amanat

Hossein Amanat (architect and urban designer)

Esther Shalev-Gerz (artist)

Daniel Roehr (landscape architect)

Robert Kleyn (architect, project manager)

David Lieberman (architect)

Essay: This broken world is represented as a half-sphere formed in white marble. The cut of the sphere is not clean, rather it is jagged, uneven. Poised at an angle and standing 20 meters wide and 14 meters high, this bisected sphere will be a landmark recognizable from the distance, while on closer view offering an immersive experience of recognition and commemoration.

The abstract form of the half-sphere is a contemporary marker for those who have perished, for those deprived of their homes, communities and families. It is also a marker for those of us living today, insofar as the world has been halved for every human being who was born before and those born after the Holocaust. One cannot differentiate the separable from the inseparable.

As a universal form, this monument can also convey loss for people in a country like Canada, which offers refuge for those who have been forced to leave their worlds behind.

This half-world seems to float over a meandering wall that first cuts the site into two halves, then ties it back into unity as the visitor moves through it. The gentle curves of the wall define a large gathering space for mourning?and remembering, for commemorative ceremonies and individual experiences.

Inscribed on the wall are quotes sharing personal testimonies, thoughts and reflections of the Holocaust. These words by survivors, poets and writers, filmmakers, historians and public servants offer reflective moments of personal experiences. Now that those who have survived the Holocaust are passing away, the gift of their words is an invitation to the visitor to read, to remember and to share.

It is through speech that we populate the silence so it may never happen again.

Team Klein

Dr. Debórah Dwork and Jeffrey Koerber (Holocaust scholars)

Essay: One of the monument’s three structures soars above the other two, its upward sweep conveying the renewal of life among Holocaust survivors and the Jewish community that has continued to flourish. The granite of the transcendent structure, with its remarkable gradation from dark to light symbolizes rising out from horror, the resilience of the human spirit and the heroism of survivors.

The exterior of the second of the three structures will be planted with birch trees and meadow grasses symbolizing the common landscape between Canada and Eastern Europe and the inescapable deeper links of remembrance and acknowledgement of responsibility. The Germans named the death camp Birkenau after the Polish village of Brzezinka, whose name stems from the birch trees found in much of the area.

Upon arrival at Birkenau, the belongings of the condemned prisoners were taken and stored in a large warehouse, ironically called Kanada because it was an unreachable place of wealth and abundance. Forests offered Jews a place of refuge but they also served the perpetrators as a place of execution. And, at the most fundamental level, the trees embody nature’s power of healing, regeneration, adjustment and growth after trauma. The birch trees symbolize the continuity of life, even through epic tragedy.

The third structure represents the importance of the number three in Jewish life and sacred contexts. Significantly, ancient Jewish teaching says that the world stands on three pillars: study, work, and acts of lovingkindness. The third letter of the Hebrew alphabet, gimmel, is derived from the Hebrew word “gemul” which means both reward and punishment. In relation to the proposed monument, the three sides speak directly to the eternal strength of the Jewish people and humankind’s capacity to choose between good and evil.

The design also responds to the three-sided site, which evokes the potent negative symbolism of the triangle, which the Third Reich used to classify people deported to concentration camps.

The monument creates a meaningful connection to the Holocaust for all visitors, including those who have no direct link to it or to its victims, opening their hearts and minds to an understanding of the Holocaust for both its historic specificity and as a universal metaphor of evil. It fuses moving image, sound, and landscape into a solemn all-embracing experience with the widest possible appeal.

It impresses upon visitors the evil of this atrocity so that they examine and confront the dangers of silence and the consequences of indifference, helping to ensure that its horrors will never be forgotten. It encourages visitors to remember with sensitivity and solemnity the millions who died and suffered, along with the resilience of the survivors, perpetuating and honoring their memory among future generations.

It evokes the lives of those who perished, celebrating the vitality of the human spirit even in the face of hopelessness and annihilation and it engages visitors by the use of significant and meaningful all-enveloping multimedia works of art, creating a memorable multi-sensory experience.

Team Lord

Essay: The star that the Nazis forced millions of Jews to wear throughout Europe, in ghettos and in camps, to exclude them from humanity and to mark them for extermination, remains the visual symbol of the Holocaust. The Nazis and their collaborators also?used the triangles that comprise the star to label homosexuals, Roma, Sinti, Jehovah’s Witnesses and political and religious prisoners for murder. People with disabilities were the first targets of mass killing. When the Monument is seen from the green roof of the War Museum, the symbol of the star becomes clear.

“The Journey Through the Star” as designed by architect Daniel Libeskind is organized with two physical ground planes: the ascending landscape that points to the future and the descending plane into the Memorial.

People enter the Monument from Booth Street and descend between two tilted geometric structures: one polished concrete; the other a mesh screen that references incarceration behind fences of often electrified barbed wire through which a landscape is still visible.

At the bottom of the descending landscape we arrive at the “Gathering Place” which can accommodate up to 1,000 people for events such as National Holocaust Remembrance Day (in April), International Holocaust Remembrance Day (in January) and Human Rights Day (in December).

The space is traversed by a railway track embedded in the ground reminding us of the trains that transported people to their death. Surrounding the Gathering Space are tilted geometric concrete and mesh structures that create six triangular thematic spaces for contemplation and reflection.

Team Saucier

Essay: The new monument is envisioned as a geological form emerging from the earth, lifting a portion of the Canadian landscape. This geological event symbolizes the process of becoming, the creation of a space for living, a place where the power of memory turns toward the future but whose roots remain implanted in a past whose repercussions we continue to live.

The monument is not merely an object erected in space as one might expect. It is a path, a passage, a form of “space-time” through whose moments of discovery and meditation we experience a range of emotions and epiphanic realizations.

The “passage” is analogous in its commemorative significance to Pesach Passover, whose literal meaning is to “pass through”, to “pass over”, to “go beyond”. The passage — a “materialized memory” — is therefore comprised of these three principal stages, notions that will shape our personal experiences sensorially and cognitively. Indeed, as we pass through this architecture of memory, we are not spectators but active participants, actors.

Approaching the site, we first discover a large tectonic plate rising out of the ground, an erupting landform having originated in the continent of Europe, symbolically heavy with the sediment of human history. Its emergence from the earth, one of the most fundamental things that humanity literally shares, creates a promontory overlooking air, space, and sky — opening toward the future, toward hope, toward infinity.

The effect is twofold: we initially sense the earthquake that has occurred — the enormous upheaval that the Holocaust has represented in history, a tragedy whose proportions and terrestrial depths have never ceased to touch us; yet, we also begin to understand that out of the unfathomable turmoil rose the human spirit, whose triumph and resolve became a springboard, or gateway, to the only kind of freedom that such elevation could engender: the freedom to live, freedom from oppression, freedom from tyranny.

The monument’s plinth, under which the path leads, transforms into a large elevated platform that structures our emergence to a higher plane, the culmination of our procession — symbolizing our journey to freedom, an arrival to a new horizon of humanity after having been plunged into and confronted by the memory of the most inhuman depths of despair.

We understand, then, that the monument is not solely an object of memory, but an authentic place of experience in which we can witness firsthand two vital sides of testimony: the powerful descriptive evidence human history, which brings to us the past, to ideas of resurgence and of resurrection; and secondly, the unwavering testament that we leave behind — that of the recognition, strength, and perseverance, which we bequeath to future generations as a legacy that enables them to face the future with even more humanity.

As the visitor begins to grasp this simple, yet rich architectural form and has contemplated the weight of its powerful symbolism, one is invited to enter through the threshold. In these first spaces, one discovers a darkened interior volume emblematically evocative of the terrible moment in history to which the monument is devoted.

The opaque interior surfaces gradually give way to luminous space, squares of light though which the sky is seen and reflected. The visitor moves from darkness to light, metaphorically from grief to hope, aware that the memory of the inhuman, of the horrific, awakens in us a fuller understanding of the Rights of Man according to The Principle of Hope articulated by the great Jewish philosopher Ernst Bloch. These “carre?s de ciel”, or “squares of sky”, open a vertical perspective through space, mediated by the vault, to suggest that a “passing beyond” is possible.

They are the glimpse of light and air for which humanity has an inherent need, especially in the darkest periods of its history. The interventions on the stone walls and interior space of the monument emphasize the continuous dialectic of earth and air, dark and light, revealing the essential work undertaken by memory when provoked by such traumatic events as those of the Holocaust.

The final stage of this lived-memory experience employs specific artistic and architectural forms conceived to lead the visitors up onto the plinth itself. Leaving behind the darker, stone surroundings for the expansive green space that covers the tectonic, sedimentary plate of the monument, we now experience the roof, whose vegetal environment is left free, wild, and fallow, recalling the site’s landscape into which the monument’s built form integrates — much like the memory of the Holocaust has integrated into our lives.

The lookout offers views to the world around us, to the ever-changing sky, toward the infinite, to life victorious over the deadly forces of history. In short, it looks out toward the possible, toward openness. Physical space impresses upon us the depths of experiential memory as we journey along the monument’s path — from inside to finally rising outward and above.

Team Szylinger

Ron Arad (artist/architect)

Essay: When faced with the daunting task of creating a memorial to honour the victims and survivors of that most recognized of collective human travesties, one cannot escape a fundamental conundrum. How can a monument in the public realm evoke the enormity of the catastrophic experiences of the Holocaust – experiences which defy abstraction or simplification, by virtue of being so specific, so traumatic and so vast?

Furthermore, the Holocaust Memorial is a Canadian monument honoring the victims and survivors of events which took place a great distance away from Canadian soil, and which are now reaching the edge of living memory.

The monument centers on an array of thin walls or foils, each up to 14m in height and 20m in length, spaced 120 centimeters apart from each other – just enough for a visitor to pass through in single passage. While we resist prescribing an ‘experience’ or enforcing didactic content onto the memorial, our proposal does pose a central, unavoidable theme – the voyage the visitor makes through these foils must be made alone.

The passage in-between the foils, recalls a key biblical reference – the Covenant of the Pieces: a pivotal event which symbolizes G-d’s bond with the Patriarch Abraham and his descendants, and the promise of deliverance following long-endured hardships.

The Covenant was sealed by a column of fire which traveled in-between an array of sacrificed animal pieces, searing them in the process. This also resonates with the Latin meaning of the word Holocaust (Holocaustum): ‘burnt offering’ or ‘a sacrifice completely consumed by fire’.

The higher reaches of these foils are individually articulated through dramatic folds and impressions to create an undulating, and at times frayed appearance. These are redolent of the imprints, or scars which events may leave in their wake – the tracery of damage which is both testament to history, and a mark carried into the future.

There are 23 concrete foils in total, facilitating 22 pathways – one for each country in which the Jewish community was decimated during the Holocaust. Their combined impact is an interplay between robustness and frailty, cohesiveness and fragmentation - like pages in a book, or individual members in a tight-knit community.

Team Wodiczko + Bonder

Julian Bonder (architect)

Essay: A Monument’s historic destiny is to preserve memory of the past and provide conditions for new responses to our lives in light of this past. As our psycho-political and ethical companions, monuments and memorials function as environments for thinking through past and present, fostering a critical consciousness. Memorial, Memento, Monument, like “Monitor,” or a guide, suggests not only commemoration, but also awareness, to mind and remind, to warn and even to call for action.

This project proposes excavating the site to expose the limestone bedrock, which is found about three to four meters below the surface (according to test pits provided by NCC). The removal of contaminated soils and cleansing of the site is a form of both physical and symbolic preparation toward the reception of new memories and histories, and new private and public commemorative and pedagogical visits and events, new consciousness toward a future free of genocide.

The Aspen trees will be planted in a mixture of Canadian soil and the soil of lands from which the country’s Holocaust survivors have come. Each year, new soils from new places will be collected and brought to the memorial, and at the annual commemoration these soils can be mixed into the beds where trees will grow. According to our estimate, this process may last until the year of 2045 or longer.

We envision this part of the project to be participatory and public, involving the diplomatic services of Canadian Government, Jewish and Holocaust related organizations, survivors and their families, as well as local, municipal and regional national governments from overseas.

We believe and hope that the events around the social, cultural and political process of collection and transport of the soil will become emotionally and historically charged and will also provide a cultural marker in places abroad from where the soil was taken.

The space is framed by Gabion Walls, which are metal baskets filled with stones. These walls, designed with specific inverted angles, will generate a strong presence of the sky, which will in turn enhance the experience of the ground. The walls emerge about two meters above the path, emphasizing the horizontal nature of the memorial, which also include a dynamic illumination system.

An eternal flame (Ner Tamid) is animated by the testimonies and memories of those who lived through the Holocaust. As an iconic symbol of life and its memory, the “speaking flame” will become at the same time an expressive and therapeutic vehicle for the speakers, survivors and witnesses of the Holocaust and later genocides. As if in intimate proximity to the speaker’s face and mouth, sensitive to each word shift in intonation and accent, the flame will become an emotional and respectful “mouthpiece”, a “porte– parole”, of and for the survivor.

Visitors will not see the survivor’s face but through the motion of the flame, animated by their speech and directly affected by their emotionally-charged voice and breath, they will be able to bring themselves emotionally closer to the witness’s testimony and experience. The process of recording and extrapolating each testimony to the flame movement will become an important commemorative and therapeutic–expressive part of the working of the Memorial.