HUD to spend nearly $1 billion on these six novel resiliency projects for NYC and NJ

By BD+C Staff

The winners of the Rebuild by Design competition, an program from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development have been announced. The competition was created after Hurricane Sandy to encourage innovative architectural solutions to protect American cities that are vulnerable to extreme weather events.

All six winners this year are from either New York or New Jersey. Check out their projects below (all renderings courtesy HUD):

Project Name: Living Breakwaters

SCAPE / Landscape Architecture

Staten Island, New York

Funding: $60 million

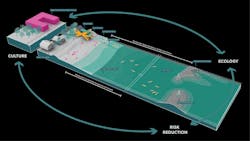

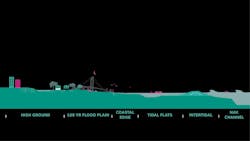

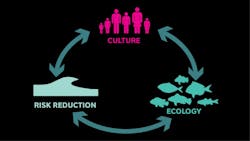

Architect's Statement: The Living Breakwaters project reduces risk, revives ecologies, and connects educators to the shoreline, inspiring a new generation of harbor stewards and a more resilient region over time.

Staten Island sits at the mouth of the New York Bight, and is vulnerable to wave action and erosion. Rather than create a wall between people and water, our project embraces the water, increases awareness of risk, and steps down that risk with a necklace of breakwaters to buffer against wave damage, flooding and erosion. We have designed “reef street” micro-pockets of habitat complexity to host finfish, shellfish, and lobsters, and also modeled the breakwater system at a macro scale to understand how and where they can most effectively protect communities. This living infrastructure will be paired with social resiliency frameworks in adjacent neighborhoods. Through the Billion Oyster Project and an associated network of programmed water hubs, local schools will be empowered with science, recreation, education, and access.

Our approach is especially suited to Staten Island’s south shore, but it is also replicable in other waterfront communities faced with the similar duality of risk and opportunity presented by their connection to the water. Tottenville, the site of our proposed Phase One pilot, was once known as “the Town the Oyster Built.” During Sandy, lives were tragically lost, and homes and parks were severely damaged. Moving forward, we can foster a vibrant water-based culture, invest in our students, shoreline ecologies and economies, and Tottenville can claim the mantle as the Town the reef re-built.

Project Name: Hunts Point Lifelines

PennDesign/OLIN

Bronx, New York

Funding: $20 million

Architect's Statement: The 1-square mile of Hunts Point peninsula is the intersection of the local and the regional in rebuilding by design. What’s at risk in Hunts Point is the hub of the food supply for 22 million people, a $5 billion annual economy, over 20,000 direct jobs, and livelihoods of people in the poorest U.S. Congressional District.

HUNTS POINT LIFELINES builds on assets and opportunities of regional importance, and a coalition of national leaders in community environmental action, business and labor, to create a working model of social, economic and physical resilience. The project demonstrates a model of WORKING WATERFRONT + WORKING COMMUNITY + WORKING ECOLOGY that applies in maritime industrial areas across the region.

Four Lifelines organized the proposal as follows:

Flood Protection Levee Lab: Flood protection that keeps a modernizing food hub dry is integrated with a waterfront greenway that opens up access to the rivers and dynamic windows on the operations and spectacle of the real working waterfront. Flood protection incorporates a string of new platforms for recreation and use on the water, and a Levee Lab of designed ecologies and applied material research. Levee Lab pilots contribute to the development of a new regulatory framework for industrial waterfronts.

Livelihoods: The Levee Lab incorporates new techniques for construction, maintenance, and research to find ways for communities to participate in building their own flood- and storm-protection infrastructure without compromising engineering or procurement integrity. If local communities benefit from the climate adaptation investments government needs to make, the value will be felt every day in new jobs, community economic assets, and awareness of the waterfront.

Maritime Emergency Supply Lines: Once the peninsula is dry and powered up, new pier infrastructure on the site of a Marine Transfer Station builds on emerging federal programs to create marine highways and improve preparedness by creating a logistics base for a Maritime Emergency Supply Chain that serves the entire East Coast when roads are impassable. The emergency infrastructure expands intermodal transport by serving commercial fishing delivery to the fish market every day.

Cleanways: A new tri-generation plant is tailored to a district with huge refrigeration demand, creating low cost and low carbon cooling and a micro-grid island when the big grid goes down. A series of strategies re-center the neighborhood around transit and connect it to the waterfront greenway. New infrastructure improves air and water quality, provides safe passage for pedestrians through truck routes, and increases local access to food.

Project Name: Resist, Delay, Store, Discharge: A Comprehensive Strategy for Hoboken

OMA

Hoboken, New Jersey

Funding: $230 million

Architect's Statement: Jersey City, Hoboken and Weehawken are susceptible to both flash flood and storm surge. As integrated urban environments, discreet one-house-at-a-time solutions do not make sense. What is required is a comprehensive approach that acknowledges the density and complexity of the context, galvanizes a diverse community of beneficiaries, and defends the entire city, its assets and citizens.

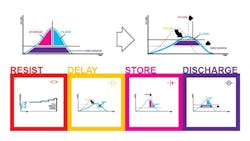

Our comprehensive urban water strategy deploys programmed hard infrastructure and soft landscape for coastal defense (resist); policy recommendations, guidelines, and urban infrastructure to slow rainwater runoff (delay); a circuit of interconnected green infrastructure to store and direct excess rainwater (store); and water pumps and alternative routes to support drainage (discharge).

Our approach is framed by a desire to understand and quantify flood risk. In doing so, we are better positioned to identify those opportunities that present the greatest impact, the best value, and the highest potential — our areas of focus. Our objectives are to manage water?for both disaster and for long-term growth; enable reasonable flood insurance premiums?through the potential redrawing of the FEMA flood zone; and deliver co-benefits?that enhance our cities. These are replicable innovations that can help guide our communities on a sustainable path to living with water.

1. Resist: Programmed hard infrastructure and soft landscape for coastal defense

2. Delay: Policy recommendations, guidelines, and urban infrastructure to slow rainwater runoff

3. Store: A circuit of interconnected green infrastructure to store and direct excess rainwater

4. Discharge: Water pumps & alternative routes to support drainage

Resist: Defense against storm surge is primarily a question of elevation. The height of flood defense measures is determined by an extreme water level analysis, which is based on storm surge water levels to defend against—in this case, a one-in-500-year storm surge water level—and expected sea-level rise.

Delay, Store: Flash flooding from rainfall occurs when rainwater overwhelms the capacity of the drainage system—water goes in faster than it can come out—the intended level of defense against this systemic seasonal flooding is a one-in-ten year flood level.

Delay strategies act like a sponge by slowing rainwater down. This slower rate of flow gives more time for the drainage to do its job.

Store strategies temporarily take excess water out of the drainage system. This water can later be returned once the system has recovered capacity.

Discharge: While Delay and Store address water going in, Discharge strategies address water going out—removing water from the system. Additional pumps, and alternative drainage routes, increase the rate in which this can occur.

Together, these complementary strategies provide a robust, cost effective, system of defense that no single strategy can deliver.

At Weehawken Cove, a park landscape serves as a defensive wall, protecting Hoboken, Weehawken, and critical regional utilities from storm surge. Wetlands provide a natural filter, mitigating potential Combined Sewer Overflow events. Both enhance recreational amenities for the community and future development.

Along Washington Street green infrastructure measures—such as permeable paving, rain gardens, and bioswales?help manage the city’s surface water and reduce the risk of flash flooding from rain; whilst enhancing the cityscape. Along the extents of the Hoboken Light Rail, otherwise discreet rainwater storage initiatives are connected to make a green circuit. This system serves as the foundations of a parallel green drainage infrastructure; reducing the risk of flash flooding from rain, filtering and cleaning storm water and serving as a park for the community.

Our proposal results in a continuous, defended, New Jersey Shoreline; and a sustainable path to living with water.

Project Name: New Meadowlands: Productive City + Regional Park

MIT CAU + ZUS + URBANISTEN

The Meadowlands, New Jersey

Funding: $150 million

Architect's Statement: The New Meadowlands project articulates an integrated vision for protecting, connecting, and growing this critical asset to both New Jersey and the metropolitan area of New York. Integrating transportation, ecology, and development, the project transforms the Meadowlands basin to address a wide spectrum of risks, while providing civic amenities and creating opportunities for new redevelopment.

The Meadowpark is a large natural reserve made accessible to the public will offer flood protection. It connects and expands marshland restoration efforts by the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission, and makes them accessible. Around and across the Meadowpark the team proposes an intricate system of berms and marshes. These protect against ocean surges, and collect rainfall, reducing sewer overflows in adjacent towns. The Meadowpark adds value to surrounding development through its views and recreational offerings.

The Meadowband defines the edge of the Meadowpark, offering flood protection, connections between towns and wetland, and opportunities for towns to grow. The Meadowband consists of a street, Bus Rapid Transit line, and a series of public spaces, recreation zones, and access points to Meadowpark. The Meadowband brings together different systems (such as transport, ecology, and development) and different scales (from local to regional), as well as local residents and visitors from further afield who will gather at this new civic amenity.

The park and the band protect existing development areas. In order to be worthy of federal investment, it is imperative to use land more intensively. We propose shifting land-use zoning from suburban (single story, freestanding, open-space parking around structure) to more urban. Single-story warehouse zones should be up-zoned to become multi-story; areas around the Meadowband would be zoned to include multi-story residential opportunities. These decisions over time will enhance the brand and identity of the basin, increase up the value of the land, and the ratable tax returns for the towns concerned.

Within the larger framework of New Meadowlands, we have identified three pilot areas to host the first projects. The northern edge includes sections of Little Ferry, Moonachie, Carlstadt, Teterboro, and South Hackensack. The eastern edge shown here contains Secaucus and a portion of Jersey City. Finally, the southern tip consists of South Kearny and the western waterfront of Jersey City.

Living with the Bay: A Comprehensive Regional Resiliency Plan for Nassau County’s South Shore

Interboro Team

Long Island, New York

Funding: $125 million

How do we keep Long Islanders safe in the face of future extreme weather events and sea-level rise? How do we ensure that the next big storm won’t be as devastating to the region as Sandy? And what can we do to improve the water quality and quality of life in the region? What can we do to make “bay life” safer, healthier, more fun, and more accessible?

These are the questions we address in Living with the Bay, our comprehensive regional resiliency plan for Nassau County’s South Shore. The goal of the plan is to make the communities around the South Shore’s bays more resilient in the face of future extreme weather events and sea level rise, but also strengthen what makes living near the bays great in the first place.

Because the region faces multiple water-based threats, there is no “silver bullet” solution. A surge barrier might protect Long Islanders from storm surge, but it won’t do much to keep us safe from nor-easters and other rain events that routinely flood our communities. Withdrawing or retreating from the coast would result in less flood damage, but the South Shore is certainly not going to throw in the towel. And neither should it. There’s a reason why people live on the South Shore: it’s a great place to live!

We think there is a better way to live with the bay!

Our preferred “buffered bay” scenario presents a range of integrated adaptive measures that keep Nassau County residents safe, and add to the economic, ecological, and social quality of the region. These measures include mitigating the damage from storm surge, storm water runoff, and sea level rise by recovering the sediment system and strategically deploying protective measures like constructed marshes, dikes, and cross-structures along the urbanized edge; managing storm water in order to mitigate the damages from common rain events as well as improve the water quality in the bay; and expanding housing options in high and dry areas near public transportation.

Living with the Bay: A Comprehensive, Regional Resiliency Plan for Nassau County’s South Shore.

Acknowledging that there are no “silver bullet” solutions to coastal protection, we propose an integrated, multi-pronged approach, which includes planning and design at the scale of the region, five sub-regions, and specific sites.

Strategies For The Barrier Island: The Smart Barrier

Due to their location and topography, Long Island’s barrier islands are among the region’s most vulnerable zones when it comes to sea level rise and storm surges. Here we propose protective infrastructure that doubles as a landscape amenity to provide access to the bay-shore, and as storm water landscape, where storm water is stored, cleaned and replenished.

Strategies For The Marsh: The Eco-Edge

While Wetlands — and in particular, saltwater marshes — play a critical role in buffering coastal communities, urban development has negatively impacted Nassau County’s wetlands. We propose new marsh islands that reduce wave action, improve the bay ecology, and afford new recreational opportunities.

Strategies For The Lowlands: Slow Streams

The areas around Southern Nassau’s north-south tributaries are threatened both by surge water flooding and storm water inundation. We propose to address these threats — along other challenges such water quality, ecological recovery and aquifer recharge — through a set of interconnected interventions, transforming rivers into green-blue corridor that both store and filter water, provide public space as well as room for new urban development.

BIG U

BIG TEAM

New York, New York

Funding: $335 million

Architect's Statement: The Big U is a protective system around Manhattan, driven by the needs and concerns of its communities. Stretching from West 57th street south to The Battery and up to East 42th street, the Big U protects 10 continuous miles of low-lying geography that comprise an incredibly dense, vibrant, and vulnerable urban area. The proposed system not only shields the city against floods and stormwater; it provides social and environmental benefits to the community, and an improved public realm.

The proposal consists of separate but coordinated plans for three contiguous regions of the waterfront and associated communities, regions dubbed compartments. Each compartment comprises a physically separate flood-protection zone, isolated from flooding in the other zones, but each equally a field for integrated social and community planning.

The compartments work in concert to protect and enhance the city, but each compartment’s proposal is designed to stand on its own. Each compartment was designed in close consultation with the associated communities and many local, municipal, state and federal stakeholders; each has a benefit-cost ratio greater than one; and each is flexible, easily phasable, and can be integrated with in-progress developments along the City’s waterfront.

Bridging Berm provides robust vertical protection for the Lower East Side from future storm surge and rising sea levels. The Berm also offers pleasant, accessible routes into the park, with many unprogrammed spots for resting, socializing, and enjoying views of the park and river. Both berms and bridges are wide and planted with a diverse selection of salt tolerant trees, shrubs and perennials, providing a resilient urban habitat.

Between the Manhattan Bridge and Montgomery Street, deployable walls are attached to the underside of the FDR Drive, ready to flip down to prepare for flood events. Decorated by neighborhood artists, the panels when not in use create an inviting ceiling above the East River Esplanade. At night, lighting integrated into the panels transforms a currently menacing area into a safe destination. Panels can also be flipped down to protect from the elements, creating a seasonal market during the winter.

The east and west boundaries of the Battery were key inlets during Hurricane Sandy, allowing floodwaters to rush into Lower Manhattan and shut down the nation’s – and the world’s – premier financial district. Enhancing the public realm while protecting the Financial District and critical transportation infrastructure beyond, the Battery Berm weaves an elevated path through the park. Along this berm, a series of upland knolls form unique landscapes where people farm, sunbathe, eat and engage with world class gardens.

In place of the existing Coast Guard building, the plan envisions a new building programmed as a maritime museum or environmental education facility, whose form is derived from the flood protection at the water-facing ground floor. This signature building features a “Reverse Aquarium” which enables visitors to observe tidal variations and sea level rise while providing a flood barrier.

For more on the Big U, click here.